Four flags are hung at the entrance to Port Adelaide’s heritage-listed Waterside Workers Hall. These flags are the Australian national flag, the Aboriginal flag, the Australian maritime flag, and the Eureka flag. Hung vertically at door height, slightly overlapping, you have to touch them in order to enter the hall. The Workers Hall as the exhibition space for Brad Harkin’s Loss. Gain. Reverb. Delay, presented by Vitalstatistix in association with Tarnanthi Festival of Contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art 2017, is an important heritage site in its own right. We are on Kaurna land in a building built by the Waterside Workers Federation in 1927. For Harkin, who identifies with both his Anglo Australian and Narungga Aboriginal heritage and has a family history of trade unionism and ties to Port Adelaide, this work is both a form of personal pilgrimage and the continuation of his installation-based practice, working with digital media.

Knowing something of the hall and its role in the Port Adelaide’s cultural and political history, I admit to pausing as I entered the exhibition space, wondering if the flags might be a new permanent addition, unconnected to this specific exhibition. But, as it turns out, they are a key entry point to Harkin’s installation. To walk through the flags is to have an intimate encounter with them: a threshold-crossing moment. Which ones do you want to touch you? Which ones are you willing to brush aside, and how will you do this? I elect to grab, then push to the doorway, the Australian flag. It feels like it’s the one that I can manipulate, or is at least the one I would most like to have out of my view. The Australian Aboriginal flag and maritime flags can more or less stay in place. But it’s the Eureka flag that I’m the most conflicted about. There’s that post-Cronulla tendency to associate it with Neo-Nazis. Thankfully, in an old union hall, the association between the Eureka flag and left-wing unions feels the more palpable one. Here, the flag regains the more earnest spirit of an earlier time, as part of a more progressive national project.

Once inside the exhibition space of the main hall we see a large, black theatre curtain drawn into a circle, stretching almost the full distance from floor to ceiling in the middle of the hall. Out at the edges, in each of the four corners of the room, four speakers play a sound work that loops and bounces from speaker to speaker. I catch snippets of dialogue: references to childhood, union life and labour: “start work at 14, dead by 35,” “grandpa quit the mines early,” “badge day every three months, made sure everyone paid up.” Mentions of scabs, wharfies, and “standing on poverty corner” defer to the working class history of Port Adelaide. The narrator seems to be actively recalling personal memories, but also speaking on behalf of others through a series of recollections and quotations. Later I learn that the audio is Harkin himself reciting notes from some of the key conversations he has had throughout the development of the work. This was a process which included talking with Kaurna elders, local historians, family members, and former work colleagues of his father who was a maintenance fitter and shop steward at the Mobil Tank Farm in the adjacent suburb of Birkenhead. Augmenting this are conversations Harkin had with his mother’s family, who have strong ties to Broken Hill and the mining industry.

A series of complex, partially constructed portraits emerge – of Harkin’s father, Harkin himself, the Waterside Workers Hall as a site for cultural events (including an appearance by African American singer and activist Paul Robeson), the historical solidarity between Aboriginal rights and the trade union movement – all of which reverberate through the space. The title of the work, Loss. Gain. Reverb. Delay, speaks to the distorted, fragmented nature of memory, but also the persistence of sound, and a resonant material culture. Harkin borrows terms commonly associated with the amplification of recorded music to capture the spoken word and replay these cultural signals into the present. But it also tells us something of Harkin’s working method: directly engaging with the history and architecture of the hall, holding close conversations with community members in the Port Adelaide area, collecting symbols of historical significance, and placing his own family history at the centre of this inquiry.

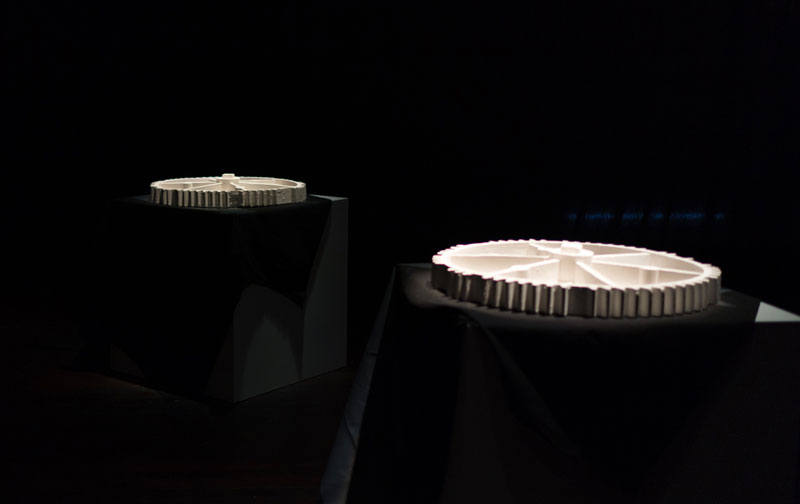

A similar process of amplifying cultural material is cast into the sculptural works presented here. Inside the curtain walls, there are seven cubed pedestals, each draped with a painted grey-black ghost version of the Eureka flag design. The loss in Harkin’s title is perhaps felt at its most explicit here, as the emblems call to mind the draping of flags over funeral caskets. Atop each of these flags are seven identical patternmaker’s cogs, cast in plaster from an original recovered by the artist and repurposed for the exhibiton. The original cog had been deemed culturally significant to Port Adelaide and placed in storage during construction of the controversial Newport Quays waterfront development. Part of a more general global trend towards an “urban entrepreneuralism,” the development sought to reconceptualise Port Adelaide’s industrial waterfront “as a future landscape of cosmopolitan consumption and professional occupancy.”[1] Reproduced in white plaster, these cast cogs reference the loss of jobs and industry in the area, through waves of automation and containerisation processes stretching back to the 1960s. In particular, Harkin draws on the experience of his father, who we imagine witnessed the effects of some of this automation and the changes this brought to Port Adelaide during the 1970s and 1980s.

Harkin’s contribution to the Tarnanthi catalogue parallels the layered presentation at Vitalstatistix. Using the same cut-up approach as the sound work at Waterside, Harkin provides a transcript of a conversation with his brother Danny. Alternating the sentences and phrases of the justified typescript in shades of grey like a form of Situationist lettrism, the text zips through their memories of their father (“He got into an industry that gave him a sense of purpose and belonging”) Port Adelaide (“Growing up with you, visiting Dad down in Semaphore, is where that all began”), and their own relationship to union involvement (“Competition. It’s complicated”). The accompanying catalogue image is of Robert William Harkin’s Amalgamated Engineering Union card from 1968, presented at actual size. It is a poignant addition: two adult men trying to better understand themselves by coming to grips with their father’s working life, piecing together what they can based on fragmented memories and archived objects of work, life and solidarity.

Harkin and his brother acknowledge the generational shift, that their relationship to union membership isn’t the same as it was in their father’s day. Brad and Danny, like many of us, are less involved, less engaged. But this is no accident. While in 2017 the “gig economy” is presented as a force delivering us all into mutiple precarious short-term engagements, there are two comments in Harkin’s audio stream that are telling: “Howard stopped union fees coming out of wages/Howard stuffed it all up.” While it was the Labor governments of 1983–96 that introduced the idea of decentralised “enterprise bargaining,” it was the Howard Liberal government’s introduction of successive pieces of legislation which worked against union membership and collective bargaining, culminating in the government’s fateful “WorkChoices” legislation introduced in 2006, which saw union membership in Australia drop to less than half the rate of twenty-five years earlier, within a year.[2]

In conclusion, Loss. Gain. Reverb. Delay evokes a time when union involvement was central to people’s working lives and the formation of their identities. It appears at a time of renewed investment and interest in Port Adelaide, with cultural organisations and small businesses opening up and a new mixed-use development replacing the failed Newport Quays project of last decade. The outcome of a richly embodied research process, Loss. Gain. Reverb. Delay avoids what art historian and critic Claire Bishop terms the “short-term seductions of captioned sensibility”[3] of research-led exhibitions, where artists use history as kind of ornament to decorate the present. Instead, through his relational, socially engaged base for practice, Harkin abstracts the various historical and emotive elements, generating a meditative and affective installation work. Ultimately, this is where the work is at its most compelling: as an atmospheric portrait of the artist filtered through the lens of family, community and working life, as a kind of “double echo” through the resonant walls of the historically significant Waterside Workers Federation hall.

Footnotes

- ^ Susan Oakley and Matthew Rofe, “Global space or local place? The Port Adelaide Waterfront Redevelopment and Entrepreneurial Urban Governance,” State of Australian Cities Bi-annual Nation Conference, 2006, Griffith University.

- ^ David Peetz and Barbara Pocock, “An Analysis of Workplace Representatives, Union Power and Democracy in Australia”, British Journal of Industrial Relations, 2009: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8543.2009.00736.

- ^ Claire Bishop, “History Depletes Itself”, Artforum, vol. 54, no. 1, September 2015: https://www.artforum.com/inprint/issue=201507&id=54492.