.jpg)

Making Modernism offers a re-examination of modernist traditions in Australia by testing connections between Georgia O’Keeffe, Margaret Preston and Grace Cossington Smith. This exhibition, which marks the first major showing of O’Keeffe in Australia, has set up an association between the three artists as a means of mapping shared knowledge, practices and innovations. A century on, it shows how the formation of both artistic and cultural conceptions of experience and place are embedded in the historical apparatus of modernism and its regionally specific applications. As the title of the exhibition suggests, contemporary understandings of modernism are still in formation, and the curators submit that a key motivation was to better understand the global and local contexts of this phenomenon. Cody Hartley, curatorial director at the Georgia O’Keefe Museum, asks in the catalogue, “what is Australian modernism and why don’t I know about it?”[1]

Margaret Preston and Grace Cossington Smith were innovators of their generation. Preston became a key figure in the development of modern art in Sydney. Cossington Smith's oeuvre explores aspects of the urban-suburban expansion of Sydney. This embodiment of place can be compared to Georgia O’Keefe in the northern hemisphere, whose decision to move to Abiquiú, New Mexico is its own riposte to the conventional account of modernism as a development generated in Paris and New York.

.jpg)

All three painters are women of Anglo-European heritage working in lands that are ancestrally foreign to them. They represent scenes of domestic habitation and a world under construction presenting diverse responses to new vistas and forms. One of the most edifying features of the exhibition is its investigation of genre, in response to landscape and still life traditions. This frontier context in both Australia and the United States provides the setting for a series of landscape paintings from each artist, while a selection of still life compositions frames interior views out to the exterior world.

The proposal to re-examine the traditions of Australian modernism using O’Keeffe as an interlocutor for Preston and Cossington Smith is useful. Organised into three sections, Making Modernism traces developments in the style and practises of Margaret Preston and Grace Cossington Smith, before moving to a generous (tantalising rather than comprehensive) sampling of Georgia O’Keeffe’s works, ranging from the 1920s still life details of shells, foliage and flowers at Lake George, New York to the later meditations on the landscapes of New Mexico. Looking to each artist’s engagement with still life and landscape as highly productive spaces of artistic innovation, the exhibition emphasises the significance of modernist abstraction as the application of formal experimentation to distinctive subject matter.

Preston’s engagement with Australian Aboriginal art, and Cossington Smith’s fascination with the building process of the Sydney Harbour Bridge represent formative moments for artists grappling with the impetus to find a new, more immediate syntax, or to capture the fleeting moments of modernity. Preston’s use of Aboriginal forms can be paralleled to the Dutch New Zealander Theo Schoon’s interest in Maori carving and his attempts to develop a vocabulary that blended indigenous tradition with European modernism. Likewise, Cossington Smith’s Harbour Bridge series might be compared with representations of the Eiffel Tower in the work of French artist Robert Delaunay.

.jpg)

As a disclaimer, Hartley states in his introductory essay that “O’Keeffe, Preston and Cossington Smith were not chosen for this exhibition because they were women, but because they are among the most distinct and influential modernists in their respective nations.” But, it does seem highly significant that all three artists are women of Anglo-European heritage working in settler societies. The artistic aim of parsing the distinctive character of their respective inherited lands into modernist painterly style can perhaps be seen to impose a new layer of colonial conquest over these same grounds.

The focus on still life and flower paintings supports a domestic worldview that could be regarded as proprietary, as the gaze of the homemaker and occupier. In the work of Preston, in particular, the incorporation of native flora and produce framed, arranged and classified through an acculturated European worldview goes some way to align progressive modernity with the new nationalism at the heart of these rigorous, self-defining motifs that support a new confidence in an Australian lifestyle. Preston’s incorporation of Indigenous Australian motif into her landscape painting might invite further critical analysis on the issue of appropriation in her work, and how these sympathetically envisioned but awkward cultural positions can be seen to enact a version of what Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang have called “settler moves to innocence”. [2]

D & JT Mortlock Bequest Fund 1982 © Margaret Rose Preston Estate

The first section of the Heide galleries presents Margaret Preston’s exploration of these parameters in her significant focus on still life and interior settings that follows from the subject matter of earlier Australian women artists like Minnie Boyd and Thea Proctor. This series of closely framed interior still lifes by Preston are high-keyed, sometimes dramatically constricted compositions. The vertiginous assembly of teapot, cups and tablecloth in Thea Proctor’s Tea Party (1924) offers a response to Cubist mannerism. The disorienting tableau carves the domestic setting into plains of lurching verticality, as the cutlery and utensils are crammed up against the front of the picture plain into the space of the viewer.

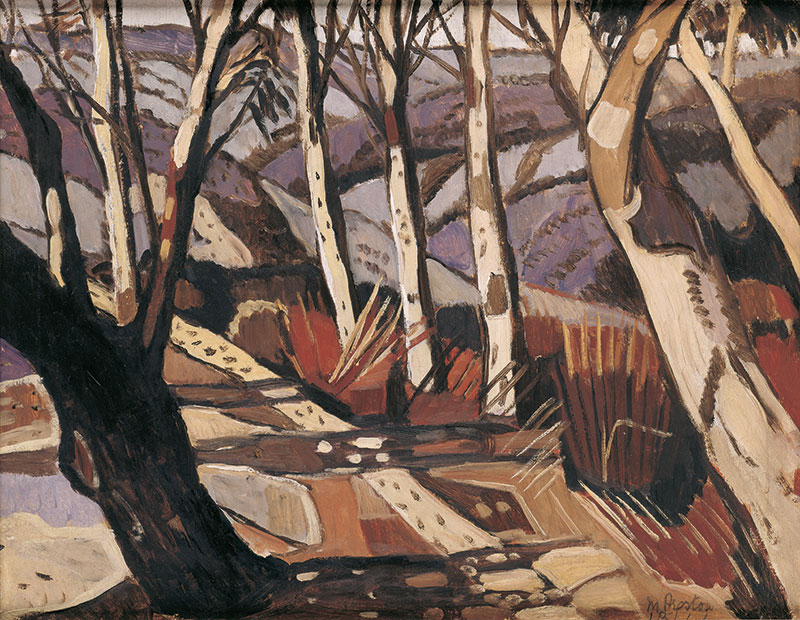

Preston’s landscapes are similarly dense with active linear treatment and flattened pictorial space. In Aboriginal Landscape and Blue Mountains Theme (both 1941), hard lines segment and restrict the viewer’s gaze. Have flowers ever seemed so stiff and intransigent as they do in her Aboriginal Flowers or Western Australian Gum Blossom (both 1928), or her portrayal of an unyielding Banksia (1927)? An obvious connection simmers between O’Keeffe’s famous flower paintings – witness the amplified Petunia No. 2 (1924) in the adjoining gallery – with Preston’s hard-edged renditions of flowers and tabletops.

The decision to lead viewers in to the exhibition with O’Keeffe’s Pink and Green (1960), placed as it is on a partition wall facing the entrance, sets up a relationship between O’Keeffe’s spacious compositions, and the tense, somewhat severely ordered settings of Preston’s. Where O’Keeffe flows, Preston halts. Reading this comparison, the tension of Preston’s compositions and the unfamiliar, uncanny space they craft makes a strong statement of unease in applying the European formalist tradition to an Australian setting.

The influence of French Post-Impressionism on Grace Cossington Smith is clear in her dappled, pointillist inflected mark-making, and her well-known sympathy for the mystic colour theories of Theosophist Beatrice Irwin that informed her belief in painting a world “through colour vibrant with light”.[3] Cossington Smith’s Sydney Harbour bridge series, as in her work showing the bridge arching triumphantly upward in The Bridge in Building (1929) and the studied focus on the department store interior in The Lacquer Room (1936), present heroic narratives of Sydney’s urban expansion. In her outdoor scenes, the fauna and contours of landscape are conduits of feeling. Works like Pumpkin Leaves Drooping (1926), and the seascapes at Thirroul and Bulli painted shortly after the death of her mother, reverberate with inner sensation. These more affective qualities of interiority also support an appreciation of the lifestyle of leafy Turrumurra on Sydney’s north shore as a threshold space of suburban transformation, captured in her 1956 painting The Window.

Two works from O’Keeffe’s Patio series, In the Patio III (1948) and In the Patio VIII (1950), create a similar liminality in domestic spaces of habitation that has clear sympathy with the spatially dense compositions of Preston’s early still lifes and Cossington Smith’s luminous light-filled, interiors. The exhibition really hinges on the O’Keeffe works. The careful selection may at times leave one wanting more, but the choice to pair an array of her Lake George and New Mexico landscapes with a focussed excerpt of her still life paintings connects the narratives explored in the Preston and Cossington Smith galleries to the nerve centre of this exposition. In comparison to the two Australian painters, there is a vastness in O’Keeffe’s canvases; in Pelvis IV (1944) the sky widens infinitely out to the stratosphere, even as it is only glimpsed through the bone socket. The inclusion of Blue Line (1919) provides a satiating moment of visual pleasure figured as enquiry into the void. Underlining O’Keeffe’s own assertion that the objective is never too separable from the abstract, the work exemplifies her claim that, “abstraction is often the most definite form for the intangible thing”.[4]

In emphasising this threshold condition of abstraction, Making Modernism affirms a deliquescence of forms over the moulding of absolute imperatives. But the meditations on place and on the inner spaces of artistic production found in this exhibition also propose other lines of enquiry. The shared concerns of place, space and experience found in this selection might well have been extended to include a more nuanced reflection on European responses to Aboriginal art and ideas of modernist experimentation. The reflections on the hybrid character of an “Antipodean modernism” could also have considered works by artists like Rita Angus, Frances Hodgkins, Dorrit Black or Elise Blumann among others, to support research into gender and genre more specifically. While this exhibition presents an accomplished and well-chosen set of comparative works, it also misses out on the potential for radical alterity that Georgia O’Keefe permits.

Footnotes

- ^ Cody Hartley, ‘Margaret Preston, Implement Blue, 1927’, in Lesley Harding and Denise Mimmocchi (eds), O’Keeffe, Preston, Cossington Smith. Making Modernism, Art Gallery of New South Wales and Heide Museum of Modern Art, 2016, p. 10.

- ^ In a discussion around plea bargains in Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, ‘Decolonization is not a Metaphor’, Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 1–40, 2012: http://decolonization.org/index.php/des/article/view/18630/15554

- ^ Denise Mimmocchi, ‘Unveiling Nature: landscape in the epoch of the Spiritual’, Making Modernism, p. 43.

- ^ Georgia O’Keeffe quoted in Kyla McFarlane, Making Modernism, p. 92.