Articulate Project Space is a Sydney-based, artist-run initiative (ARI) with exhibition space and artist studios on Parramatta Road, Leichhardt. Previously an auto-mechanics, the renovation designed by Jisuk Han (an architect who specialises in museum projects) incorporates the kind of stylish simplicity befitting a commercial space, but with the ethos of an ARI.

The exhibition Blueprint / Picture Start curated by Helen Grace, presented in the smaller upstairs gallery, is approached up wooden stairs recycled from timber crossbars once used on ramps to stop cars rolling backwards. Sue Pedley’s cyanotypes (Blueprint) line one wall of the L-shaped mezzanine. Towards the front of the building, Virginia Hilyard presents three screen-based works: Picture Start and Dust Data are compiled from 16 mm colour film offcuts with ambient soundtracks; while for Flatbed (in monochrome) a film editor silently loops. The artists are regular collaborators, although this exhibition puts their individual works side-by-side, as if engaging in a form of parallel play. Flatbed acts as a technical hinge between the two, and the exhibition as a whole gains its traction around what curator Helen Grace terms “the analogue digital” or “media archeology”.

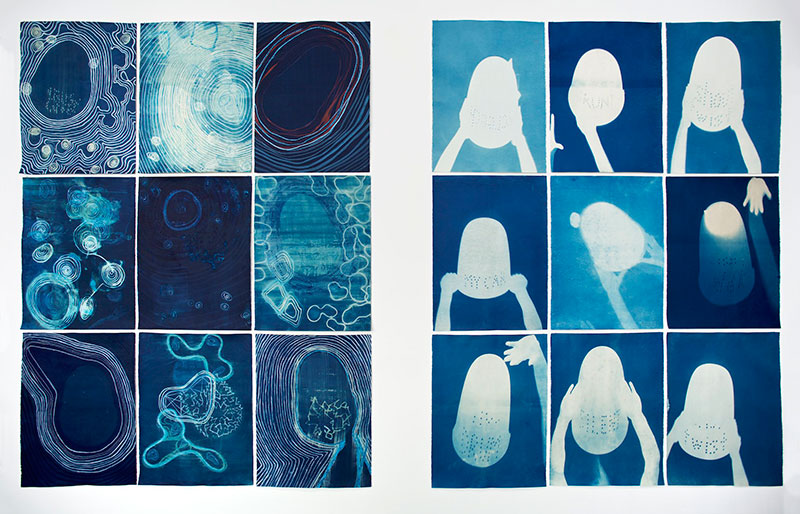

Cyanotypes intrinsically reference the discovery of modern synthetic pigment (eighteenth-century colour-maker Diesbach discovered Prussian Blue by accident while trying to make red, due to contaminated potash), and Pedley’s process retains this experimental approach (especially when compared to the precision of digital colour). Pedley’s prints were achieved outside lab conditions, using variable environmental solar exposure (they are salvaged from a series she made over a decade ago, although it is a process she is reticent to revisit given its potential environmental toxicity). While Todd McMillian is concurrently showing abstract cyanotypes, framed and printed onto Belgian linen, at Sydney’s Sarah Cottier Gallery, Pedley’s works are on paper and assembled into three blocks of nine squares, working as much en masse as individually.

Hilyard’s cut-up films also sequence a series of stills, from film offcuts she salvaged from refuse bins and scanned using old slide mounts at high resolution so that the celluloid damage is marked up. Focusing on the splice points, and clearly contaminated by tape marks and other residue, Hilyard says she set out to disprove the old adage that you can’t make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear. The elusive narrative bricolage of Picture Start and slower layering of Dust Data prevent the viewer ever fully fixing the aesthetic object (something that might have happened had these film stills been exhibited, as originally planned, using light boxes).

In this way, the printed image (Pedley) and moving image (Hilyard) is given its respective due glory, yet across both artists’ work there’s a focus on the constituency of chemicals and light. On reaching the top of the stairs of the gallery space, you are immediately beckoned by the wall of blue to your left and, as you enter further, a flickering luminosity, against which the space retains a sense of elevation, right up to the exposed ceiling beams. While this is clearly a post-industrial warehouse, with a view looking out onto Paramatta Road, in this exhibition it came across as transfigured into the interior of a cathedral.

With a female gallery owner and a female architect involved in the genesis of Articulate, and this exhibition by two female artists and a female curator, there may also be a gender poetics at play. The smell of sump oil that must once have permeated the walls, and the industrial inheritance of its machinic enterprise, is also reflected in the understanding that Pedley’s father was a surveyor, Hilyard’s parents were both architects, and there’s a further technical lineage in Pedley’s work stretching back beyond the architectural blueprint to the historical legacy of Anna Atkins’ delicate botanical photograms from 1842 (although the ecological footprint of the process was not of the same concern to Atkins).

At the artist talk for the exhibition Hilyard referred to the dust, hairs and other imperfections on the film that resonated for her in rifling through the family detritus (finding a preciousness within what’s otherwise considered junk). Hilyard’s work avoids any sense of the abject from “hairiness” and accentuates the sticky spoils of degeneration in terms of texture, layering and hue. One audience member asked to what extent this was an exhibition engaged with forms of nostalgia: it’s there in the leader frames of Picture Start (the numbers, crosses and text) and the retro-aesthetic. An early member of Sydney’s super 8 film group in the 1980s, now teaching film production at Sydney College of the Arts, Hilyard responded that this technology doesn’t seem anachronistic to her. She’s using it in similar experimental ways with her students today (indeed, it’s their found footage off-cuts she’s incorporated, recovered from the trim-bin). In this way, her films create a new digital event from a discarded cinematic archive at least twice over. There’s a forensic nature to the composition, taking time to search through the dross and the dreck, yet these films are also a symptom of using the materials at hand (they are contemporary and “workaday”).

Pedley is similarly interested in using everyday materials. Many of her cyanotypes are sculptural, depicting plastic buckets inscribed with pinpricks of text (although, despite the arms that provide scale, I originally saw them as magnified thimbles, corresponding with the idea of “digits” that Grace writes about in her curatorial essay). In the middle sequence the images are more cellular looking, perhaps also evoking the microscope but with less precision (Pedley has also re-exposed and painted over this abstract section of images introducing other colours and creating a textile effect).

It’s clear that the ambit of this work goes beyond printmaking – there’s a latent potential for animation (as if the images could be wrapped inside zoetropes), sound (the words inscribed on the buckets are taken from birdsong and Beatles lyrics) and sculpture (Pedley has previously exhibited similar prints and three-dimensional objects in the garden at Heide). The inclusion of the artist’s arms in the bin series also implicates artist labour, so the images themselves become bodily and performative.

The painter Agnes Martin (who as an avid swimmer worked with blue) wrote in a 1973 essay “The function of art work is the stimulation of sensibilities, the renewal of memories of moments of perfection”. On this perceptual level there is a clear engagement with colour and light in Blueprint / Picture Start, even though the work of both artists is very process-based (something Hilyard’s Flatbed makes explicit) and neither are purists. I’m left wondering how much of the resonance between the two working worlds is contained in the splice, teased out further by the curatorial discourse in terms of the various “articulations” leaping the synaptic gap between two artistic nervous systems.