In 2016, the ongoing conversation surrounding the visibility and promotion of female art practices has again surged in prominence. This renewed scrutiny owes a great deal to the release of Elvis Richardson’s CoUNTess Report[1], a data collection and analysis project that Richardson has been running since 2008, tracking gender inequality in contemporary art. Under the slogan of “women count in the artworld”, the CoUNTess Report demonstrates that despite the fact that there are significantly higher proportions of women graduating from tertiary visual arts courses, men still receive disproportionately more representation across all spectrums of the visual arts, whether that be solo museum shows, monographs, reviews, or museum acquisitions. Media commentary on recent blockbuster art exhibitions have also noted the dearth of female art, notably in Adrian Searle’s review of the Abstract Expressionism survey at the Royal Academy in London[2] , and Melbourne arts blogger Natalie Thomas’s excoriation of the National Gallery of Victoria’s Melbourne Winter Masterpiece exhibition, Degas: A New Vision in a blog post titled “NGV #cockfest”.[3]

This September, the multi-venue feminist project Vote For Me seeks to go some small way to rectifying this historic imbalance. In response to the ubiquity of artworld #cockfests, the exhibition’s title and its underpinning curatorial premise deal explicitly with the idea of the promotion and visibility of female artists. Brigid Noone and Kate Power, operating as the curatorial team PowerHouse, have united Adelaide’s network of artist-run-initiatives – FELTspace, Fontanelle and Format – to stage a sequence of interlinked shows, featuring twelve artists from the eastern half of the country. It’s impressive that Vote For Me feels less like a disconnected sequence of discrete ARI shows and more like a mini-biennale. Although united under a single title, the works are geographically dispersed and sorted into complementary clusters. The tongue-in-cheek poster promoting the exhibition resembles an electoral campaign image, humorously boosting the Powerhouse team to the status of celebrity curators. The curation of each separate space is gentle, yet able to draw out resonances between disparate practices.

Fontanelle Gallery plays host to works by Sydney-based trio Hissy Fit and the artist and curator Frances Barrett. These performances possess a punishing physicality. Live on the opening night, Hissy Fit’s Heaven is a techno-horror mini-rave, emphasising the “macho grotesquerie” of the club scene. The three artists, Jade Muratore, Emily O’Connor and Nat Randall, clad in white tracksuits and wrap-around mirror shades, perform a hyper-kinetic dance routine to a soundtrack of sexually aggressive club staples. Waving glow sticks and spitting neon blue sports drinks across the gallery walls, the 45-minute performance demands huge physical endurance; occasionally the deafening pulse of the music would die, making audible the ragged exhalations and shuffling footsteps of the artists. The difficulty of accommodating a one-off live art performance inside the span of a month-long exhibition is hinted at by the lonely detritus and single- channel video documentation of Heaven in the main exhibition space, which feels desolate after the seething energy of the opening night.

Barrett’s The Wrestle, projected in Fontanelle’s second gallery, is the video documentation of a live performance from last year’s 48HR Incident at 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art. In it, Barrett engages in a freestyle wrestle with one of the exhibition curators, Toby Chapman, in a double-or-nothing gamble for her artist’s fee. Outclassed by her male opponent’s height and weight, Barrett is destined to lose her wager and forfeit her artist fee, underscoring male privilege. Watching Hissy Fit’s exhausted limbs tremble, the audience twitched and winced each time Barrett was slammed to the mat. These works complement each other to draw out the implication that for a woman to enter into this male-dominated arena, the #cockfest artworld, is also a physical grapple, bruising and wearying.

The role of the female body as a subject for art is contemplated in the FELTspace iteration of Vote For Me. The passive female muse, a model for male artists, is done away with; this space is full of depictions of women in which men are almost entirely removed from the equation. Mia van den Bos’s The Selfie is Mightier Than the Sword is a digital painting printed onto satin, depicting van den Bos and fellow artist Ashleigh D’Antonio photographing themselves against a backdrop of paparazzi camera flashes. Both women possess the familiar absent gaze of the selfie-taker, eyes glazed with self-regard. This is not a gaze that follows you around the room; it doesn’t care about you, guys. The women are their own muses. This purposeful self-construction of the image and identity is carried through in Romi Graham’s Shoplifters Will Be Prosecuted, a stall of hand-painted t-shirts inscribed with oppositional slogans railing against wage inequality, party politics, internet surveillance, gentrification and sexism. Although scattergun in their approach, these slogans are none the less entertaining: “I’ve never shanked a sexist man and all I got was this lousy t-shirt”.

Other works in the FELTspace galleries demonstrate an embodied awareness of female physiology, alluding to a world of corporeal sensations that even the most studious male observer could little hope to comprehend, let alone depict. Mary-Jean Richardson’s pair of paintings, entitled Watching The Body, show, on one canvas, an anatomically precise twinned couple of female pelvic bones, floating over a fleshy pink ground and, on the other, a more abstract suffusion of red paint rising from a dark ground which seems to suggest the sensation of blushing. In the back gallery Sasha Grbich’s Learning The Language of Sleep is an assemblage of oddly resonant components that imply an anxious probing of the body’s inner workings. A soundtrack repeats words gleaned from sleep-talk recordings, as though trying to decipher communications from the unconscious; a glass tank of salt water is maintained at 37 degrees Celsius, the median point of healthy human body temperature; and “a heavy object” is “nestled” in a cavity in the gallery’s false wall. These two artists’ works combine to generate an imaginative, troublingly dispersed conception of the female body, one that contrasts neatly with van den Bos and Graham’s concentration on surface and appearance.

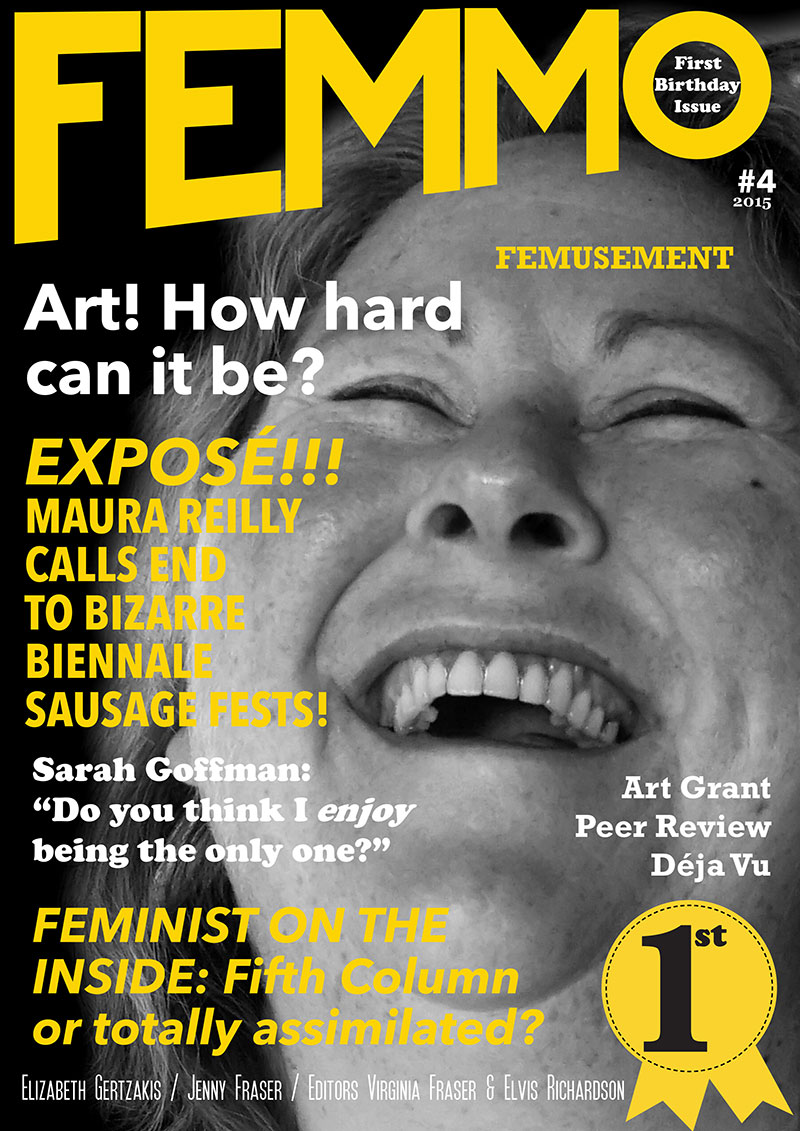

The visibility of female artists and the manner in which they are incorporated (or not) into the art-historical cannon is tackled in the Format Gallery space. Elvis Richardson and Virginia Fraser’s FEMMO™ project is installed along one wall of the gallery. This punchy, provoking work was a recent winner at the Fremantle Print Award. A sequence of six huge silkscreens purport to be the covers of the as yet hypothetical FEMMO™ magazine and adopt that format to display portraits of female artists with provocative headlines and “grab” quotes, imagining “a world where feminism is central to, and informs, every topic”. Similar strategies are employed in Asleigh D’Antonio’s 1800 VALI DATE, a single channel video work that satirically emulates and disrupts late-night TV commercials for phone-sex chat lines. Accompanied by a sleazy, smooth jazz soundtrack, the soft focus camera lingers over the artist’s body, as she wittily invites man-splainers to call in and explain the male gaze to her. These two works combine to generate a charged parallel reality, one in which familiar structures are disrupted and remixed, subverting comfortable assumptions of male dominance and female passivity.

The explicitly tactical approach to female representation used by FEMMO™ is leavened by Sera Water’s work, which cleverly implies the manner in which women’s art practices have historically been rendered invisible by a diminution of so-called “craft” work and a dismissal of the domestic space. Waters incorporates embroideries into familiar household towels to create a kind of invisibility cloak that hovers ominously in the centre of the gallery space. Elsewhere, a massive, circular vinyl enlargement of an embroidery is adhered to the gallery wall, with the artist’s face camouflaged amidst the bucolic farmstead scene.

The curatorial notes, which accompany the exhibition, are constructed as a dialogue between the curators Noone and Power, ruminating on the means by which female artists might be promoted, and the need to “be ok with taking up space”. This back and forth supports an acutely self-conscious awareness of the oddity of the female-only exhibition and works to rationalise this discomfort. Ultimately the curators arrive at the conclusion that it’s “eas[ier] to promote someone else’s work and [be] in a collective … being committed to circular promotion”. They talk about the need for “back-up”. In her blog post “NGV #cockfest”, Thomas despairs: “I’m so bored of men telling each other how great they are.” Vote For Me goes some small way to tipping the scale the other way.

Footnotes

- ^ See http://www.thecountessreport.com.au.

- ^ Adrian Searle, 'Abstract Expressionism review – crammed in a room with the big men of US art', The Guardian, 21 September 2016.

- ^ Natalie Thomas, 'NGV #cockfest, Degas – A New Vision', 30 July 2016, https://nattysolo.com/2016/07/30/ngv-cockfest-degas-a-new-vision/.