Today, frontiers are simultaneously a condition, both tangible and imaginary, of our globalised world. Frontiers, however, can be volatile, and even fragile. While frontiers can delimit territories, they can also disintegrate. Kafka’s short story “The Great Wall of China” is helpful here. Kafka’s narrator describes the construction process: workers were divided into teams, and each team assigned a section of wall. Once the section was completed, the team would commence work again, in an altogether different location. Kafka’s point was that far from embodying a singular, continuous architectural structure, China’s Great Wall was actually an assemblage of heterogeneous gaps and fragments.

If the frontier is critically important for postcolonial and globalised discourses, so to is its inevitable dissolution, reimagining and revisioning. The multi-site exhibition Frontier Imaginaries, takes up Kafka’s parable of the partially completed structure. Straddling two venues, No Longer at Ease at the Institute of Modern Art and The Life of Lines at QUT Art Museum, the frontier is understood here as a fluid boundary that can be reinscribed and redrawn. With over twenty artists, collectives and architects, the exhibition advances curator Vivian Ziherl’s commitment to the notion of the frontier as a productive mode of contemporary critique.

Frontiers jostle and collide, creating new territories, spaces and lines of enquiry. Local and international artists are carefully juxtaposed, bringing the frontier to the fore, albeit in its Kafkaesque state of fragmentation. What emerges are rich new conversations as Ziherl neatly sidesteps well-rehearsed arguments concerning the margin and periphery. With an array of new commissions, combined with archival material drawn from the John Oxley Library and the North Stradbroke Island Historical Museum, Frontier Imaginaries is deeply invested in local history, while simultaneously exploring broader geopolitical fault lines.

Consider, for example, Melbourne based artist Tom Nicholson’s multi-part work, which sits at the intersection of documentary, process-based archival research and sculpture. Indonesia’s historical struggle for independence is combined with the unfolding contemporary tragedy of displaced peoples seeking asylum. The first part, created with Grace Samboh, Towards figures of dedication, and a flood (2015), prompts the spectator to consider the construction of Indonesia’s national identity in the wake of independence. Nicholson and Samboh worked directly with Indonesian state sculptor, Edhi Sunarso, who in the 1950s and 1960s was commissioned to create many of the new national monuments. The work serves as an extraordinary reminder of history’s elasticity and plasticity as narratives are made and remade. The second part, Scenes for an archipelago (2015–16), turns the lens back on Australia’s own borders, from the perspective of asylum seekers. Nicholson worked with groups of Hazara refugees stranded in a Javanese town. Geographical isolation, combined with a lack of transparent media access has created a representational void overseen by the Australian Government. Against this, Nicholson gently seeks to return agency to the refugees by recording individual stories.

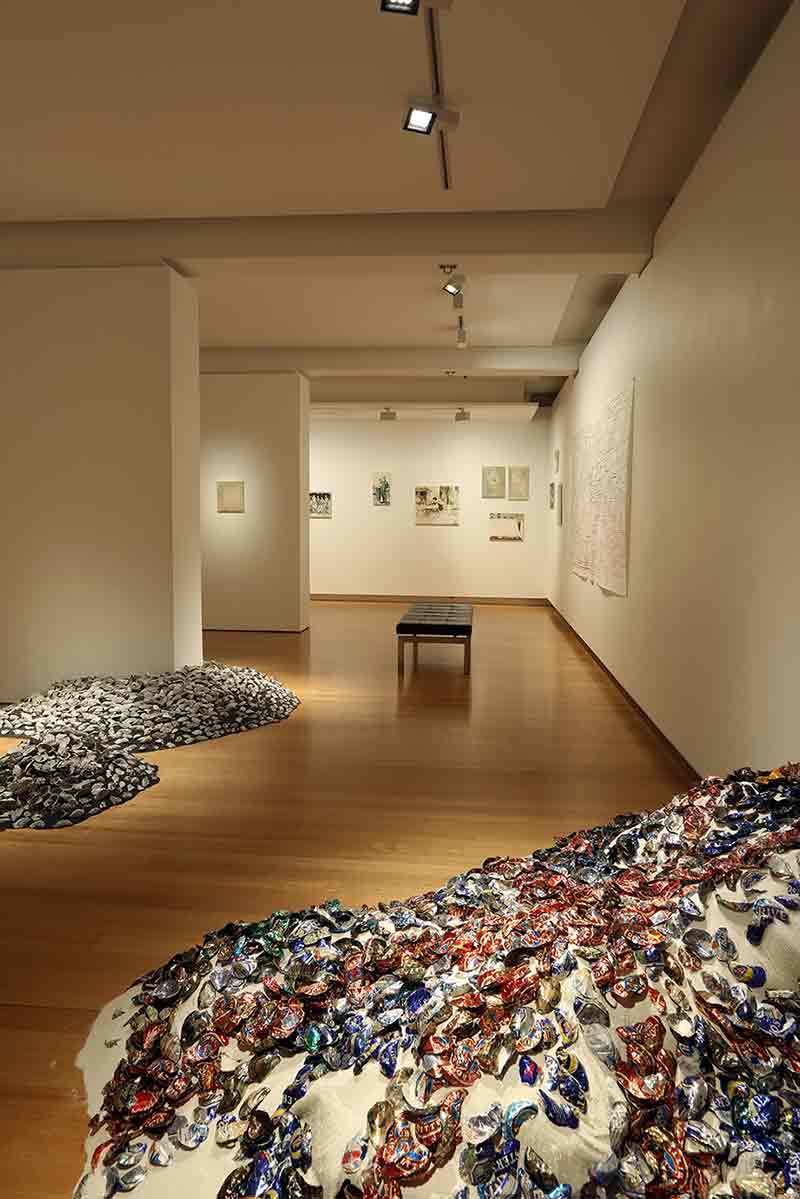

Rich in documentary and archival material, the exhibition creates uneasy relationships by clustering similarly themed works. Geological frontier exploration and the mining of natural resources are explored with the deft juxtaposition of Megan Cope’s new commission Re Formation (2016) and Helmut Newton’s photographic series documenting the construction of the Geelong Shell oil refinery in the 1950s. Across from Newton’s photographs is a 1970 documentary created by Shell’s film unit. The documentary reinforces the significance of mineral exploration, extraction and export in Australia’s economic history. Cope’s installation consists of twin middens and revisits the early settlement practice of mining middens for lime necessary for the construction of the new colony. The first midden is made from cast concrete and oyster shells. The second consists of concrete and pressed beer cans, reminding the spectator of the forced cultural displacement of Indigenous peoples in southeast Queensland. If Newton’s images celebrate the heroism of the white male worker engaged in nation building, Cope’s middens are mournful elegies to the devastating loss of local tradition and sacred sites.

The IMA site No Longer at Ease continues exploring the frontier theme, with a psychological inflection. Australia’s negotiation of its colonial history continues with Juan Davila and Martin Munz’s extraordinary video work, Ned Kelly (1983) and is a rare example of Davila’s collaborative experiments with film. Davila and Munz created a montage of found footage, early digital graphics, and family portrait photographs to create a poignant critique of Australia’s failed attempts to become a Republic. From the vantage point of 2016, Davila’s film appears as urgent and relevant as when it was first created.

The theoretical scope of Frontier Imaginaries is broad and ambitious. Without being too heavy handed, Ziherl successfully creates a series of nuanced and unexpected linkages. With echoes reverberating throughout the exhibition back to Dutch colonial history, the experience is akin to Kafka’s intervals in the Great Wall: proliferating segments behaving like dynamic assemblages as opposed to conforming to single overarching linear structure. The exhibition is scheduled to travel to Jerusalem and the Netherlands, and will no doubt metamorphose into a new set of conversations.