When the dead refuse to be buried they come back as gods to claim their kingdom. Then, raised up as martyrs, their shadow looms larger than life. This is the lesson of With Secrecy and Despatch, an exhibition of Australian and Canadian contemporary Indigenous art at the Campbelltown Arts Centre. It dutifully commemorates (from Latin commemorare “bring to remembrance”) what had long been unspoken. In this case, the repressed object is a massacre committed 200 years ago in the nearby Appin Gorge. Under orders of Governor Macquarie, British soldiers and their dogs drove a camp of men, women and children over the sandstone cliffs. Of the fourteen victims found, eleven were quickly and secretly buried on the spot and the other three hung in trees on the highest point, their black bodies swinging silently in the breeze as a warning.

One of those strung up was the Gandangara leader Cannabayagal. His lifeless body had been hauled up the cliff with great effort to make its macabre message. The Gandangara, who lived beyond the frontier, had been fighting a protracted and wily campaign on the southwest fringes of settlement and Macquarie was determined to pacify them. After being taken down, Cannabayagal’s corpse was not attended by saints and nor did it later ascend to heaven. Rather, its head was amputated and despatched to the Anatomy Department at the University of Edinburgh.[1] With Secrecy and Despatch is Cannabayagal’s apotheosis. But the exhibition is much more than a memorial (from Latin memoria “memory, remembrance, faculty of remembering”) to Cannabayagal, the Appin Massacre or colonial massacres generally. What is most striking about this exhibition is not the massacre narrative as such, but the beauty with which it is articulated. The elegance of the install is immediately apparent, creating an enduring mood that joins the individual efforts of each artist into a collective effort greater than its parts. This fulsome grace is necessary for the redemption the exhibition seeks.

Art is the most exalted form of memorialisation: it is where the gods were first pictured and made immortal. The success of this exhibition lies as much in its curation as its art: in commemorating an ugly incident in such lofty terms, the viewer is left with a clear and moving impression, even a sense of elevated reverence for these hunted victims of colonisation. Their sacrifice, the exhibition proclaims, has not been in vain. As political as these issues and indeed some of the artworks are, the curators – Tess Allas and David Garneau – seek different territory; not apolitical territory but something more than politics. Not long ago such an exhibition would have only been staged in a social history museum, where it could be relegated safely to the past. The elegance of an art gallery would have seemed inappropriate for such vexed subject matter.

The concern of the curators was not the complex frontier micro-histories of black–white and multiple Indigenous clan relations and allegiances in the area around 1816 that culminated in the massacre, but the symbolic resonances of the massacre narrative today. The truths sought here reach beyond empirical facts to an existential aching borne from intense trauma. The massacre narrative is not just about murder and brutality but also the erasure of sovereignty and identity. Only art can trace the depths of its sharp psychological cuts, which is why fine art’s most valued genre, history painting, is in the tragic mode. The massacre narrative is a significant genre of Indigenous contemporary art, and one achievement of this exhibition is a summary glimpse of its history. The genre was firmly established in the 1990s; but Fiona Foley’s Annihilation of the Blacks (1986), which is prominently displayed in the centre of the exhibition space, suggests the theme was present from the beginnings of the urban Indigenous art movement.

The massacre narrative draws on reports of actual events. While references to frontier violence rarely appeared in official histories – what W. E. H. Stanner famously called “the great Australian silence”[2] – they are ubiquitous in frontier journals, as Julie Gough shows in Hunting Ground (2016). As well, frontier violence featured in nineteenth-century moralistic tracts that condemned colonialism’s worst excesses and popular tales of colonial romance, and were passed down in Indigenous and non-Indigenous oral histories. Traditional Indigenous storytelling also incorporated frontier violence into existing Dreaming sagas – for which their tragic form was well suited – as recently occurred in East Kimberley massacre paintings. These esoteric abstract compositions quickly became iconic exemplars of the contemporary Indigenous massacre narrative. With Secrecy and Despatch includes four such works completed between 1990 and 1997 (by Rover Thomas, Queenie McKenzie and Freddie Timms). Like Foley’s sculpture, they too are fittingly displayed at the centre of the exhibition space.

The Indigenous massacre narrative is also a subset of the Western massacre narrative, for which the modern benchmark is Picasso’s Guernica (1937). This modern massacre narrative originated in responses to the First World War and owes much to Nietzsche’s influential search for a modernism that would ground contemporary subjectivity in the existential origins of being, as Nietzsche believed the tragedies of classic myths did. The similarities between Western classical myths and Indigenous Dreaming stories have often been commented on. They are evident in contemporary East Kimberley massacre paintings, which gained wide public visibility after the Blood on the Spinifex exhibition at the Ian Potter Museum of Art in 2002. The exhibition had an enviable aura, in part due to the personal experiences of the artists and the tragic history of the place. This, along with the perceived authenticity of their art and a narrative mode that embedded these terrible events in an abiding presentness – a feature of classical tragedy – earned for these works a revered place in the contemporary Indigenous massacre narrative.

The increasing prominence of the Indigenous massacre genre suggests a growing struggle to wrest national identity from the myth of white Australia that first found voice in the ANZAC memorialisation after the First World War. Whose blood will found the Australian nation: the colonisers or the colonised? This question came to a head during the 1988 bicentenary, and nowhere more so in aesthetic terms than in The Aboriginal Memorial (1988). Its 200 mortuary poles commemorate the Aboriginal dead, one for each year since the invasion. Its “conceptual producer”, Djon Mundine, meant to subvert the official discourse commemorating those who died in Australia’s numerous wars – a discourse that forgets the first war that founded this nation. Thus The Aboriginal Memorial is a founding work of the contemporary Indigenous massacre narrative.[3]

The battle for appropriate memorials to the national psyche boiled over in Australia’s “history wars” at the turn of the twenty-first century with all the psychological force of a taboo transgressed. Coincident with the Blood on the Spinifex exhibition, the history wars contributed significantly to the exhibition’s success. The wars were a reaction against the considerable scholarly research of the 1980s that had unearthed the colonial massacres occluded in official histories – Bruce Elder’s Blood on the Wattle, first published in 1988 and reprinted numerous times since, being the most significant.[4]

This research informed Gordon Bennett’s massacre paintings, which he began while still a student. Significantly, he graduated in the bicentenary year, when The Aboriginal Memorial stole the limelight at the Sydney Biennale. With Secrecy and Despatch includes The Shooting Gallery (1989), completed at this time. While not helped by the dark exhibition space, the painting lacks the concentrated angst of works from a few years later such as the 1991 Bounty Hunters series, which by their sheer force effectively established the massacre genre in Indigenous contemporary art.

Like Dada and Surrealist protests against the atrocities of the First World War that first shaped the modern massacre narrative, Bennett’s paintings are a rebuke to the repressive language of civilization and the silence it produces. As such the rebuke was as much about the trauma of language. Bennett sought to unsettle not just “the great Australian silence” but also the structural silencing of colonial discourse – of its metaphors and modes of representation. Bennett’s unstitching of this language, as well as the direct uninhibited freedom with which he increasingly painted, gave his work an unrivalled influence. Massacre narratives generally have a moral intensity that is impossible to dodge, because their stories of hapless victims and evil perpetrators humanise colonialism’s inhuman forces. Depicted as acts of particular men (in which the victims were often women and children), a specific massacre story – where we can point to the place, the documents, the victims and their descendants – has great emotional affect.

The danger of this humanist narrative is the illusion that things could have been different if only (in this case) Governor Macquarie had been a “nice man”. In fact, he is remembered as an enlightened, progressive and liberal governor, but there cannot be conquest without terrorism. The “civilizing mission” of nice colonialism, in which Macquarie believed, was a fantasy of British colonialism from beginning to end across its empire. Colonialism was never going to be a pleasant “picnic with the natives”.[5] Macquarie’s civilising beliefs underline the tragic fate of colonial endeavour. This is Bennett’s point. His paintings are drenched in an unforgiving blood that, as Macbeth lamented, cannot be washed away. There may have been nice colonists but colonialism is never nice. Better to glorify its massacres in a discourse of conquest and nation building, as happened 100 years later on the fields of Turkey and France, than to indulge the fantasy of nice colonialism.

Nice colonialism is a repressive discourse, its main feature being the production of a taboo that silences its crimes. While the Indigenous massacre narrative lifts the lid on this silence, its main aim is to break the taboo. Thus its brief is not to settle what is essentially a dispute between academics and their political patrons over empirical facts – to make a body count – but to take the pulse of those who survived. To doubt the details of conquest in the face of its ongoing trauma is a type of Holocaust denial. To stand at the Appin cataract and not see the dead is to close your mind to the Dreaming of this place. After seeing With Secrecy and Despatch you will not be any the wiser about the actual details of the Appin massacre but you will feel how place and history shape being, especially for the ever-restless heirs of colonialism’s taboo histories.

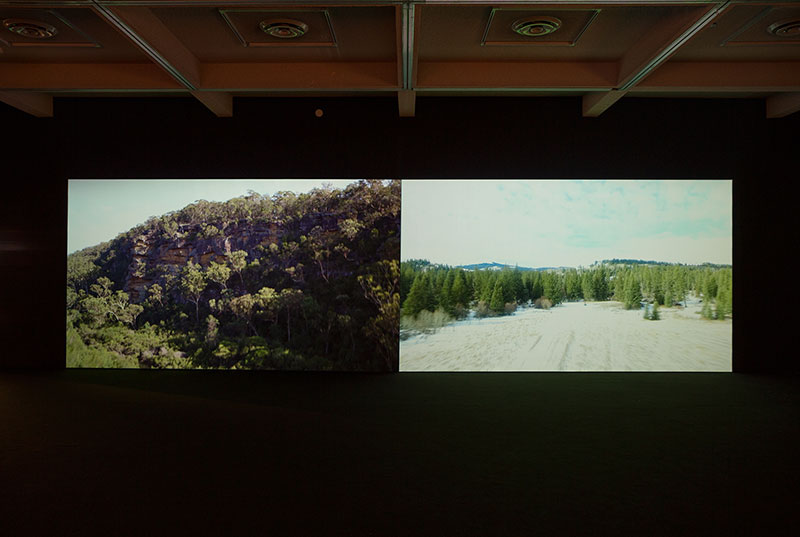

Unlike the history wars, With Secrecy and Despatch is primarily prognostic, not diagnostic, which was the point of commissioning a large number of works to commemorate the massacre. These commissions tend to be reflective, as if the artists who met together on the massacre site did not want to disturb its ghosts. One treads carefully in cemeteries. One of the most powerful works in this respect is Adrian Stimson’s As Above So Below (2016), a silent film on two large screens that rise from the floor. Composed of aerial shots that pan over the Appin Gorge and the site of the Cypress Hill massacre of 1873 in Stimson’s native Canada, what prevails is the abiding presentness of earth’s natural life-worlds calling the viewer to respectful silence. The cross-cultural matrix, explicit in Stimson’s video but implicit in the other Canadian work and the overall curatorial project, alludes to the universal nature of Indigenous experiences of colonialism and trauma in the modern age. Finding fellow sufferers is the first step to a cure.

Commissioned by the Campbelltown Arts Centre. Photo: Simon Hewson. Courtesy Campbelltown Art Centre.

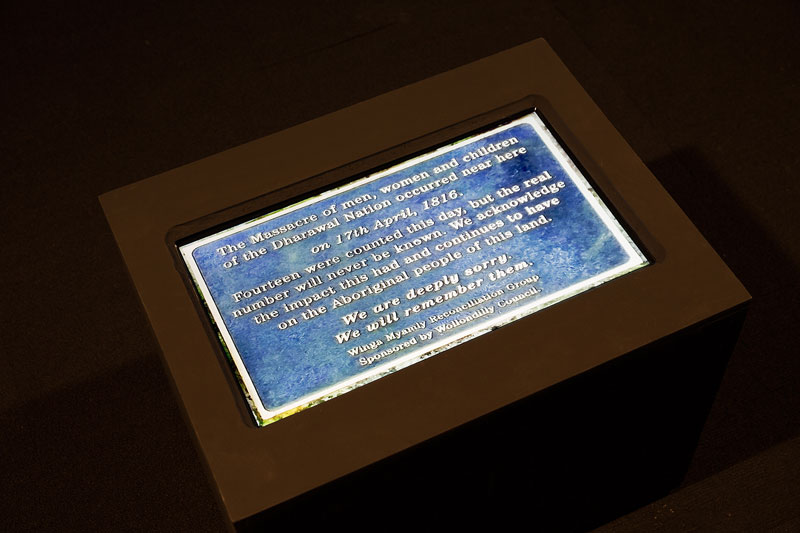

With Secrecy and Despatch does not propose a cure. At best trauma is managed, and here the management is by aesthetic means, as if contemporary art is medicine for a recovery of sorts. But it is a tricky potion, for aesthetics and the beauty it seeks is a pharmakon – both poison and cure. Here, it generally comprises an ethnocidal instrument of colonialism – the tropes and technologies of Western art – to avert ethnocide. Cheryl L’Hirondelle makes this double negative her subject. Her jump-cut editing of a journey filmed on the road to the Appin Gorge from the Tharawal Local Aboriginal Land Council (appin nikamowin (singing Appin), 2016), and interactive projection in which images of viewers appear ghost-like at the Appin Massacre memorial plaque (nipawiwin Dharawal ohci (standing up for the Dharawal), 2016), proffer an Indigenous sense of temporality and insist on the limits of redemption after colonialism’s triumph.

Contemporary art has lost modernism’s hunger for utopia. Now there is no right way but many ways. In this respect, With Secrecy and Despatch is a typical contemporary art exhibition that mixes paintings, new media and installation, and in which different paradigms jostle against the other without any clear rhyme except that which the curators provide for this moment – a carnival of retro styles crafted with curatorial finesse. There are examples of avant-garde offence (Vernon Ah Kee), melancholic introspection (Genevieve Grieves, Dianne Jones) that at times finds lyrical expression (Judy Watson, Marianne Nicolson, Rover Thomas), elegiac revelation (Adrian Stimson), conceptual didacticism (Jordon Bennett, Fiona Foley, Julie Gough) and post-conceptual appropriation (Gordon Bennett, Tony Albert).

This raft of antinomies is not just because there are 21 exhibiting artists. Rather, it reflects a characteristic of contemporary art: the desirability of abiding in difference leavened by the chance affinities of aesthetic relations. Works are juxtaposed for their decorative fit rather than any didactic or instrumental narrative, such as chronology, geography, ideology or theme, thus giving the exhibition a sure feeling but not a sure argument. This feeling takes shape atmospherically: the dark rooms, low lighting, minimal signage and particular emotions of each room comprising a carefully orchestrated ambience of real beauty.

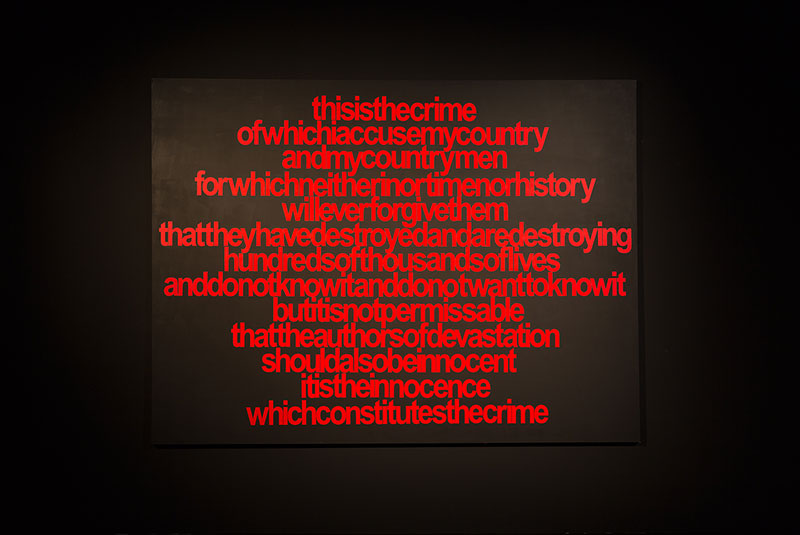

The highly aestheticised sensibility of the exhibition is also apparent in each work. Even those that miss the mark do so because of aesthetic overreach (trying too hard to be art). Indeed, this seems to be the point of Tony Albert’s three works commissioned for the exhibition. Like Gordon Bennett’s work they mix the banal and the grotesque, but with a twist of Warhol’s effete pop. This twist produces a feigned shock that masquerades as an antidote to real horror. Aesthetics – the politics of beauty that orchestrates the domain of feeling – thus triumphs over other concerns even when, as with Ah Kee, the artist’s unaffectedness is not in doubt. His angry jabs of text (taken from James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time: “this is the crime of which I accuse my country and my countrymen for which neither nor time nor history will ever forgive them …" ) and paint (from his Brutalities series) have never looked so beautiful, and powerful than in the darkened spaces of these galleries.

Commissioned by Campbelltown Arts Centre. Photo: Simon Hewson. Courtesy Campbelltown Art Centre.

All that seems left for contemporary art is this politics of beauty, as if it is a categorical imperative or transcendental condition of art. This, however, speaks of a longing for some higher order beyond history – here beyond that history which betrayed Indigenous people. This longing doesn’t contradict the trauma and anger that transparently drives the art in With Secrecy and Despatch. To the contrary, the longing is symptomatic of the exhibition’s commitment: its aesthetic dimension does not lull the audience into passive contemplation but calls viewers to action. Here aesthetics is made relational, and the call is primarily to a healing ceremony rather than a land rights rally. Thus it is difficult to remain a mere onlooker. Whatever one’s ancestry, whatever side one’s ancestors were on – and for some it was both – we are caught in the same storm.

This is the central theme of another “massacre” exhibition showing concurrently at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, When Silence Falls, curated by AGNSW’s Indigenous curator Cara Pinchbeck but to very different effect. It, too, draws on international artists, but from a wide number of places and events, not solely Indigenous related. This reflects its major conceptual difference with With Secrecy and Despatch. When Silence Falls includes an almost equal number of non-Indigenous and Indigenous artists; With Secrecy and Despatch is exclusively Indigenous. Together these two exhibitions, 50 km apart, speak to different strategies of conciliation in the aftermath of trauma, each of which has its place.

Pinchbeck’s catalogue essay for When Silence Falls begins with a discussion of the silences in official colonial discourse but the focus of the exhibition is how the aftermath of violence creates a restive silence in us all – a haunting of the disappeared. On the other hand, With Secrecy and Despatch silences non-Indigenous voices. This pointed silencing underlines the exhibition’s focus on the trauma of the colonised and the politics of voice. While these are concerns of Gordon Bennett’s art, had he been alive I doubt that he would have consented for his work to be shown in this context. He was always reluctant to be in Indigenous-only exhibitions, as they reiterated the exclusionary structure of colonial discourse and ignored the cross-cultural imperatives of contemporary art. Further, his art is particularly addressed to non-Indigenous viewers: it calls them out.

Non-Indigenous viewers do have a place in With Secrecy and Despatch. In the exhibition’s opening symposium, the Metis co-curator, David Garneau, aptly suggested the S&M nature of With Secrecy and Despatch, cheekily acknowledging the white audience patiently waiting at their whipping posts. More seriously, Garneau suggested that art (and presumably the art gallery) was a third space in which opposing discourses can engage in a type of productive diplomacy. Where, then, is the diplomacy in such a one-sided exhibition? If white audiences are steered like self-flagellating monks to the periphery of the healing ceremony, kept away from the limelight, this is because they have a very specific and delimited role: to listen attentively.

The first step on the long and difficult road of “reconciliation” – a buzzword in trauma studies – is for the traumatised to speak to the perpetrator. This national project of “reconciliation” cannot be another paternalistic white gesture: if it comes at all, it must come from the victims not the perpetrators, and it must come in their time and to their tune. With Secrecy and Despatch, more elegantly curated than When Silence Falls and also more directly political in conception, suggests that the current Indigenous generation has taken on the burden of mourning for their ancestors for whom relentless oppression left no space for grieving. Until this process is complete, do not expect forgiveness let alone conciliation. If, like Adorno after the Holocaust, it is your turn for silence, from it will come new ways to speak.

Footnotes

- ^ Grace Karskens, ‘Appin Massacre’, Dictionary of Sydney: http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/appin_massacre

- ^ W. E. H. Stanner, After the Dreaming, Sydney: Australian Broadcasting Commission, 1969.

- ^ See Djon’s Mundine’s essay in Badlands: Art & War, Artlink 35:2, pp. 24–31: https://www.artlink.com.au/articles/4277/the-aboriginal-memorial-to-australiaE28099s-forgotten-w/.

- ^ Bruce Elder, Blood on the Wattle: Massacres and Maltreatment of Aboriginal Australians Since 1788, Sydney: New Holland Publishers, 2003.

- ^ "Picnic with the natives" was a telling colonial euphemism for massacre.