.jpg)

Theorist and filmmaker Rick Prelinger suggests archiving can be considered a form of folk art. While this rings particularly true in the digital era of Tumblr and Pinterest curators and collectors, it is the compulsion to make, collect, arrange, record and file that permeates much artistic practice. This impulse is often subconscious though obsessive, a process that becomes addictive and in many cases, more important that the items themselves; books are collected for covers not content, teaspoons are deified on a customised stand.

Two recent solo exhibitions situate the artist as archiver. At Fremantle Arts Centre, Rachel Salmon-Lomas constructs a cave-like context in which to view selections from eighteen years of monoprints and etchings while Joanne Richardson presents the engaging remnants of a playful game at Maxart Office Space, a short term gallery situated within a modest office on the 25th floor of Perth's third tallest building. Sincerity abounds in these exhibitions – both artists have set seemingly unending tasks for themselves and these collections are signposts to bodies of work that may never stop growing.

Richardson is emphatic that her Sugar Exchange Program addresses a now lifelong conundrum that was initially posed when considering the social generosity of café culture and the individual’s responsibility for complimentary items. She pockets sachet gifts from cafés and adds them to her burgeoning collection. In the likely case of a double-up, foreign sachets are surreptitiously deposited into new contexts. At MaxArt, six years of travels can be cross-referenced with an accompanying inventory chart. Displayed in striking and succinct chronology along slim stands that teeter against three walls are sachets sourced from Australia, the UK, Dubai, Italy, the USA and Canada.

Through archiving, Richardson addresses the question of how best to fulfil an item’s function within the context of the complimentary. Pocketing ten sachets is both taking advantage and testing the limits of the system (although it should be noted that Richardson rarely consumes beyond the socially acceptable). In saving the unused sachets that will likely be binned if left on the saucer or slightly stained by sloshed coffee, she extends a level of respect and perhaps a furtive nod to the sustainability of invisible ephemera. The Program’s accompanying artist-talks-as coffee-dates seek to provide an entry point to these now-fetishised objects with Richardson taking on an ambassadorial role for the Program.

Like many collections, Richardson’s pursuit of this playful idea has no foreseeable endpoint. Unlike the Ikea pencils she has re-located and documented since 2007 (with the ultimate aim to place her local Innaloo pencil in Ikea’s birthplace of Älmhult, Sweden), there is no Mecca for the sugar sachet pilgrim. The swapped sugar swindle can continue indefinitely, stopping and restarting according to the artist’s whims, no one collection more important than the other.

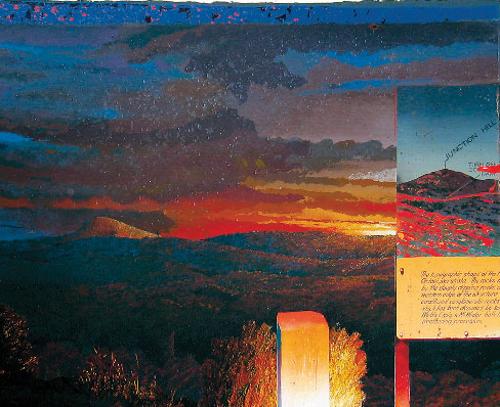

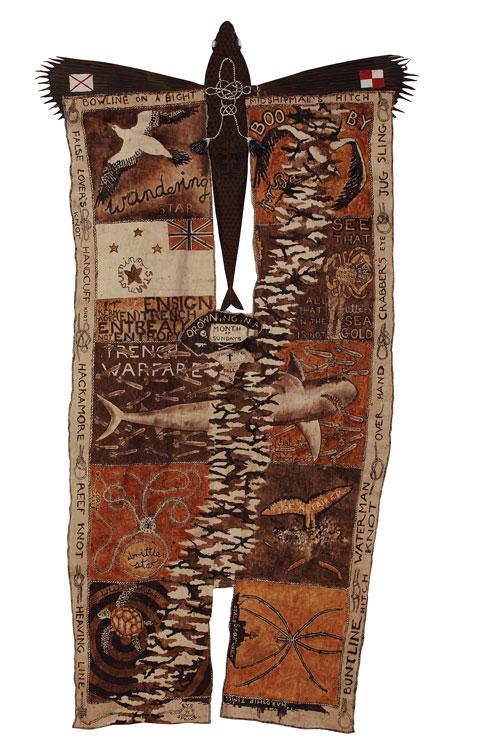

At a darkened Fremantle Arts Centre, Salmon-Lomas presents an archive of prints eighteen years in the making. In presenting the works like this she has subverted the white cube into a kind of white hole. The viewer is provided with a torch. It’s not so disorienting that feet or walls are indistinguishable but in walking closer, it’s easy to identify that the patchwork of black rectangles ahead are flecked with clues, partial narratives of fractured selves that predominantly feature the heavy-headed cow, Riley. An observant but unassuming character, Riley is used by the artist in a diaristic fashion.

The exhibition title cues us to consider how fluid states are navigated when our universe is uncertain, undefined, temporarily dissolving – a sensation echoed by walking in the dark gallery with a torch. Various permutations of sinking feelings, mental struggles and slight actions are splayed out in skilfully crafted fragments, some placed unreadably high. Self-guided through the threshold of an expansive and very personal landscape, a series of sometimes pithy, mostly weighted axioms provide an intimate point of access to Salmon-Lomas’ archive of values and behaviours.

It is hard to resist the impulse to see this archive of prints as autobiographical – a process of mirroring and self-evaluation that continues to grow, unseen. The poignant summation of the archivist’s tail-chasing impetus is evident in the exhibition’s final print. A leaning Riley is enveloped in the white glow of speed lines. It takes a moment to realise they are going the wrong way.