Half a decade ago, the impetus behind this selection of historic and contemporary artworks from the British Museum was classical and scholarly, as director Chris McCauliffe attests in the catalogue. It drew attention to the cultural power of the word and the script, something that is fundamental to the university even in the digital age. Secondly the exhibition indicated a commitment to cultural diversity, acknowledging Islam's increasing presence in Australia.

The plurality of Islamic experience and aspiration from the courtly and sumptuous monogram of Ottoman Emperor, Suleiman the Magnificent to flickering hologram hands of Fatima carstickers offering protection from the evil eye and worthy religious proverbs on the road in 1990s Cairo was celebrated. In between has come the children overboard, 9-11, detention centres, the Bali bombing and the War in Iraq. The lived experience of the exhibition and the immediacy of its impact has changed dramatically. Part of everyday reality, the exhibition now prompts more volatile and direct questions. A review of Mightier than the Sword could have happily fitted into the previous Not Happy, John issue of Artlink, had the timing been right.

The most urgent cross-reference is the most distressing, the destruction of the Museum and State Library at Baghdad, indicating the temporality of all curatorial endeavours and the marginal position generally accorded cultural endeavours in the New World Order. The mind returns to recently televised scenes of empty galleries and broken artifacts, whilst the present, securely-cherished, exhibits each please and intrigue in turn. How then can the rhetoric of justice and liberation be sustained in light of the scant regard for the destroyed museum and libraries, even granted that UNESCO, usually sceptical about Western cultural paternalism, has publicly attested that there was inside collaboration, along with unattested media rumours that Saddam Hussein had been stealthily ransacking museum treasures for raising personal funds.

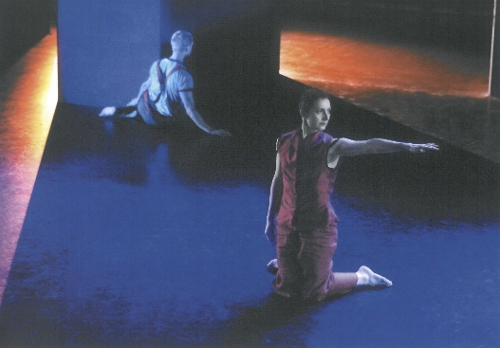

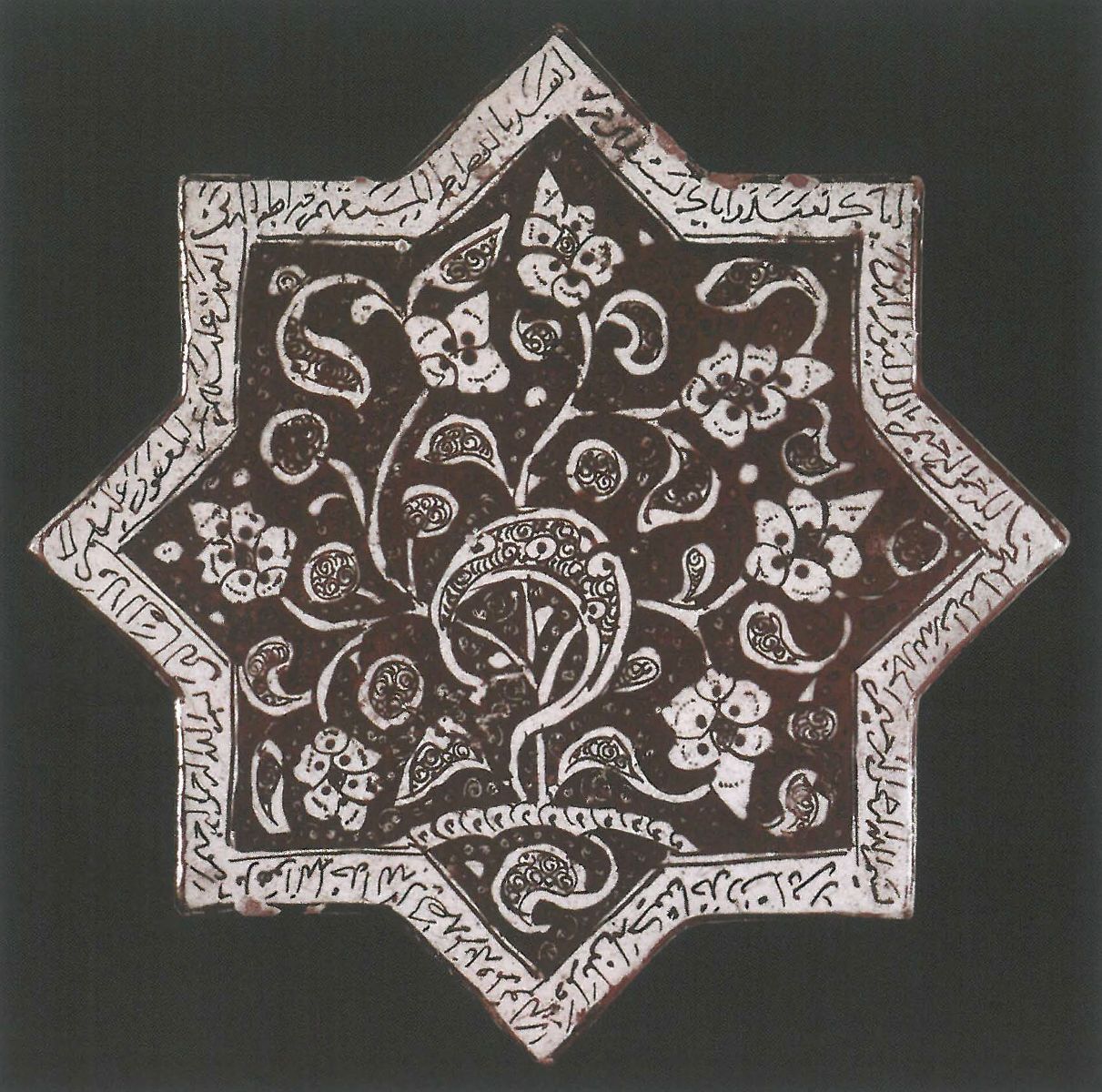

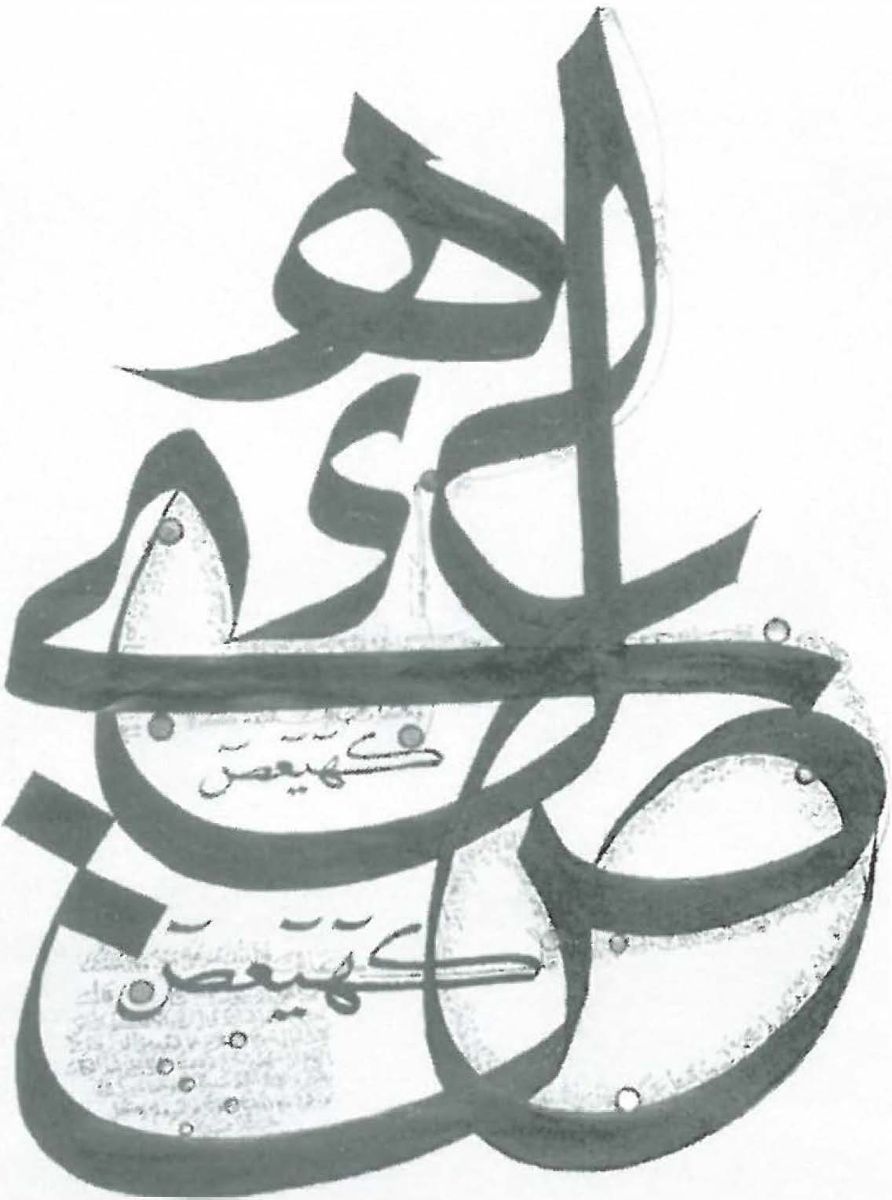

A subsection of Mightier than the Sword sampled the British Museum's collection of modern Islamic art. In the past 20 years the Museum has collected works by major living Islamic artists across many countries. These works are beautiful in themselves, gestural, fluid, sophisticated in their design and balance, indicating calligraphy's impact on mid-twentieth century formalism, abstract expressionism, tachism. In an Australian context, Tony Tuckson and Ian Fairweather's work immediately springs to mind as having been informed by the linear power of Islamic text. Ahmed Moustafa's Expending in God's Cause, 1995, oil and watercolour, is visually compelling, locking the eyes for extended periods in its shimmering energetic layering of pigment and repetition. Here the apparent polarities of Western self-expression and the so-called regulated 'freedom-less' world of Islam are mutually informative. The collected artists range from traditionalists, such as Ghani Alani, who undertook a long apprenticeship to master calligraphers whilst working in the transport industry, to artists trained in tertiary art colleges in the Middle East. Others belong to the Islamic diaspora, studying in mainstream art colleges in Britain and Europe such as Central St Martins.

The works negotiate the dominance of Western media formats and content. Artists respond to the rich compass of well-documented international art history and the sophisticated and flexible resources of the mainstream tradition, from Pollock to Sumi-e painting, yet retain the values of their particular cultural and religious background. They return to Islamic calligraphy with expanded size formats such as Rachid Koraichi's Silk Banner With Magical Signs, produced in Algeria and exhibited in Paris and increasing the simplification and arbitrary design such as Nja Mahdaoui's Untitled 1984 or Nassar Mansour's Kun, 2003, surely informed by the visual brevity yet solid narrative content of the commercial trademarks and logos. The political element of current Islamic experience is captured in Gaza-born Laila Shawa's photolithograph, Letter to a Mother, 1992, based upon Islamic calligraphy painted as graffiti in Gaza during recent Palestinian uprisings. She references the patterning and repetition by sampling and tiling original photographs of wall surfaces and overlaying the purple ink indicating Israeli obliteration of the slogans. Simultaneously Shawa invokes the feminist tradition of protest and comment in posters and printmaking that has made an international impact over the last two decades, including Australia.

In the last two decades the British Museum has made a lateral decision to deal with its colonial past by collecting contemporary art by non-Anglo-Celtic artists as mature, independent artworks rather than as ethnographic curiosities. European modernism has had a dynamic impact upon cultures far removed from it, and there has been a strong tradition of practitioners adapting selected elements and holding their own centre fast Whilst the obvious, politically correct answer to colonial collecting policies is to return the plunder, plurality and cultural diversity in collecting has merit too. If the collections of major Australian museums were to be scattered and burnt, whilst Papunya Tula painting may be retrievable to an international audience through off-shore holdings, (eg the British Museum owns a collection) what else could be assembled from overseas? The exhibition highlights the role that artists and art professionals play in validating and recording many cultures and how cultures enrich and feed each other.