Landscape representations offer up places redolent with the possibility of action. Here, if landscape and Tasmania are put together in any form, in any public environment, the possibility of action sometimes appears more about ideological argie-bargy than about the prospect of engaging with virtual or material aspects; there's no sitting on the horizon line bereft of perspective. Like all desired and envied picturesque places, these landscapes bear the stain of that original sin – nature, and the contest to win over hearts and minds can, like all zealotry, spill over into a race for conversion.

To this end, those who debate about what it is to be in place in the landscapes of Tasmania may be heartened by the opening at Cradle Mountain of The Centre for Wilderness Photography, featuring images by Peter Dombrovskis. In their time, these images were the standard for wilderness photography in this country, and figured among the most potent symbolic and iconic weapons in the battle for the Franklin River. But over-exposure has drained these images of their power to signify their creator's original intention and, paradoxically, many are now deployed as propaganda by various factions.

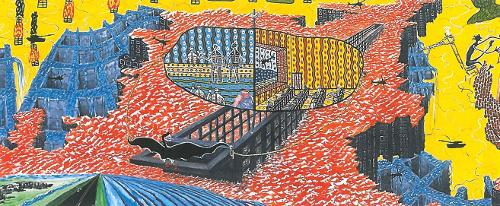

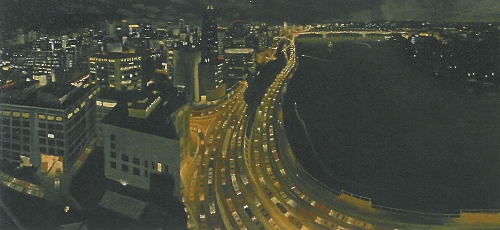

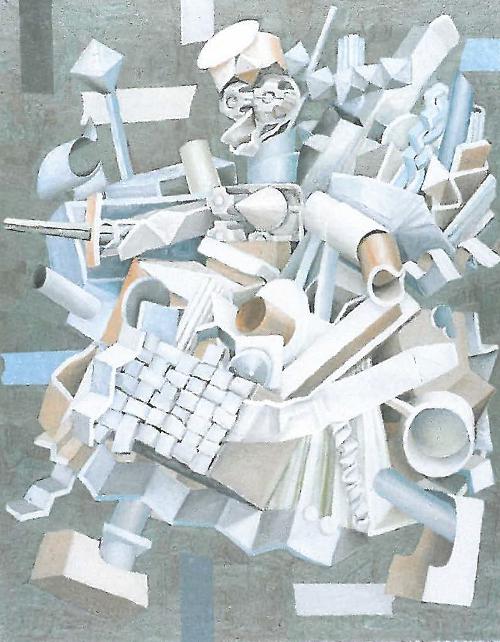

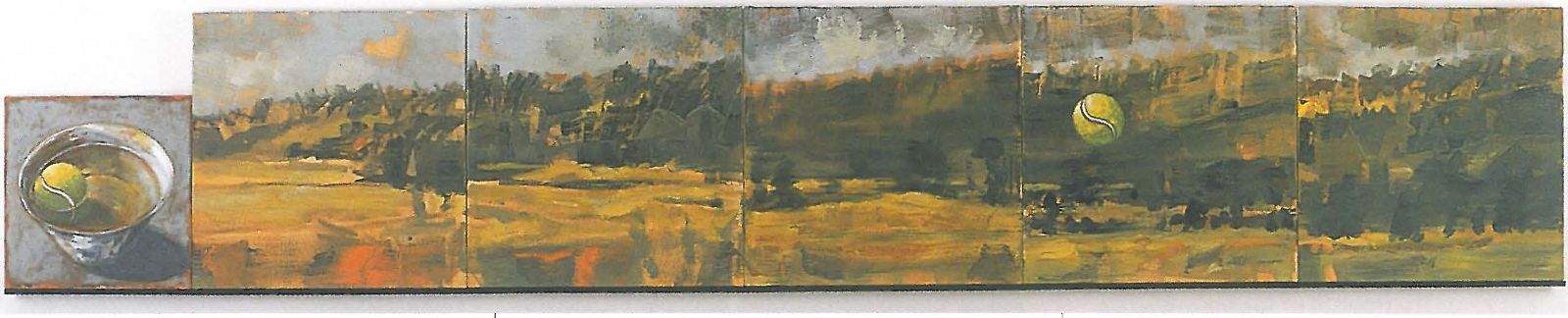

In Painting Tasmanian Landscape the vision is broad and the intention is clear. Paul Zika has curated a balanced and intelligent overview of contemporary landscape painting in Tasmania and it is a measure of the breadth, variety and talent of artists who draw on this place for inspiration. Zika's exhibition is staged as a journey through what catalogue essayist Jonathon Holmes calls the experience of 'Sensation, Map, Detail'. Many-layered and multi-faceted, like the artists exhibiting here, are representations of landscapes from the minuscule to the grandiose, from the immediately recognisable to the challengingly obscure, from the sensuous, dreamy and lyrical to the physical, transformational and awe-inspiring. The 'ideologies' in these works are informed by what Paul Zika calls 'a broader intellectual vision brought to bear on familiar locations'. Through this 'worldly conceptual outlook' the exhibiting artists present spaces and places that are, in their realisation, humanised and humanising. Each artist (Michaye Boulter, Tim Burns, Geoff Dyer, Kerry Gregan, Patrick Grieve, Christine Hiller, David Keeling, Stephen Lees, Anne Morrison, Ian Parry, Susan Robson, Richard Wastell, Philip Wolfhagen, and Bill Yaxley) exemplifies the full range and potential that professional painting of the landscape can be. Collectively their works constitute an evocative spatiality that invokes reflection on memory and identity and the materialisation of place. Two works in particular illustrate how such reflection is manifest.

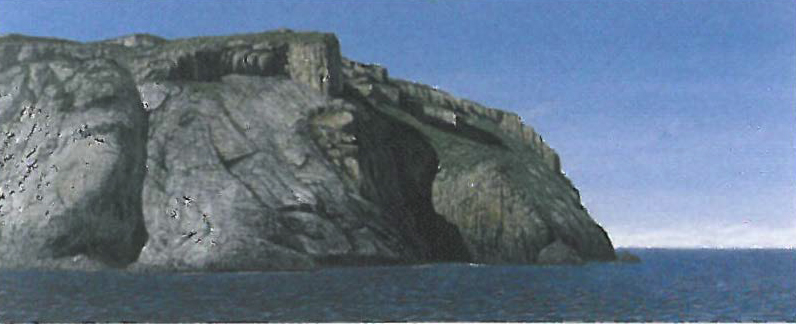

Referencing the portrayal of nineteenth century Tasmanian landscapes, Michaye Boulter's Cloudy Bay Headland goes beyond providing a pleasurably recognisable view. The verisimilitude of this work is mesmerising; stunning in its immediacy. The azure shimmers and radiates with an electric hum, the ocean oscillates and pulses a constant rhythm of colour and pattern, and the headland transforms back to the turbulent violence of volcanic ooze of its origins in front of my eyes. It is hard to reconcile the literal and abstract in this work but it is here that the pleasure lies – in the suggestion that things are not always what they seem.

Richard Wastell's Tides is reminiscent of the constancy of invisible natural forces that work upon us with enduring regularity. The perception of our place in the world is blurred and obscured by the imperceptible actions by which our beings are framed. The forces that we enact upon the world are concomitant to the forces that are enacted upon us. This painting represents a vortex of time and space within which lies an allusion that our lives are dictated by a regularity in nature but this regularity is not obvious to a mindset that is oblivious to a deeper reality.

Paul Zika elegantly orchestrates a passage through this conceptual and material terrain of artistic expression. His spatial orderings of the exhibition give to the collected works a setting in which their individual worlds constitute a uniquely composite place that rescues us from abstraction. In effect it is possible to understand where I am and thus to sharply focus on questions of being in place, of existence; all inspired representations of place permit us to do such foundational work.

Unlike other representations of Tasmanian landscape that have now been burdened with factional ideations underwritten by longstanding animosities about the proper use of land and landscape, the works in this exhibition reveal refreshing vitality and discerning eclecticism.