Did we not know their blood channelled our rivers,

and the black dust our crops ate was their dust?

O all men are one man at last. We should have known

the night that tidied up the cliffs and hid them

had the same question on its tongue for us.

And there they lie that were ourselves writ strange.

Judith Wright, “***’s Leap, New England”

At the entrance to the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery I meet Lucienne Rickard who is preparing the last drawing in her series of large-scale drawings of Tasmanian threatened species. Each drawing is erased after completion and a new species is drawn over that, as the ghosts of the prior drawing background each new one. She has been doing this since September 2019 and will complete the work in January 2021.

As I enter the museum proper I pass, on my left, the site where, for years, there existed a projected film fragment of the last Thylacine in captivity, anxiously and endlessly circulating in its concrete-floored cage at the Beaumaris Zoo. So much more powerful than a photograph for his circling last years to underscore the deep pathos of his fate, it was always a heartbreaking experience. Immediately to my right is the exhibition Ningina Tunapri which provides insights into the experiences of generations of Tasmania’s Indigenous populations to very much affirm their ongoing existence.

Entering the main exhibition spaces, I still recall and can never disregard the fact that this is the place that once exhibited Truganini’s skeleton – a tiny, plaintive object in a glass case, representing what was considered an historical inevitability. There she was, commanding respect for her formidable survival, following the brutal genocide, daring to suggest that we Europeans might be able to bring ourselves to learn, to care, to co-exist, and show respect for a people, a culture, a way of life still largely incomprehensible to those who erected this colonialist establishment to the arts and sciences.

If I was not already familiar with the work of David Keeling, these introductions would be an appropriate mindframe from which to engage with the earlier parts of his retrospective. This is the Keeling renowned for his passion in thinking through Colonialism, Ecology, Humanism and our Shame. This is the Keeling whose practice over the last twenty years is renowned for its focus – a deep immersion – in the landscape of Tasmania abjuring a more direct engagement or more literal representation of the issues, while also returning to something of the artist’s earlier mission without the rhetoric, judgement, and alienation of interpretation that was so prevalent in the highly self-consciously language of painting in the 1980s and early 1990s.

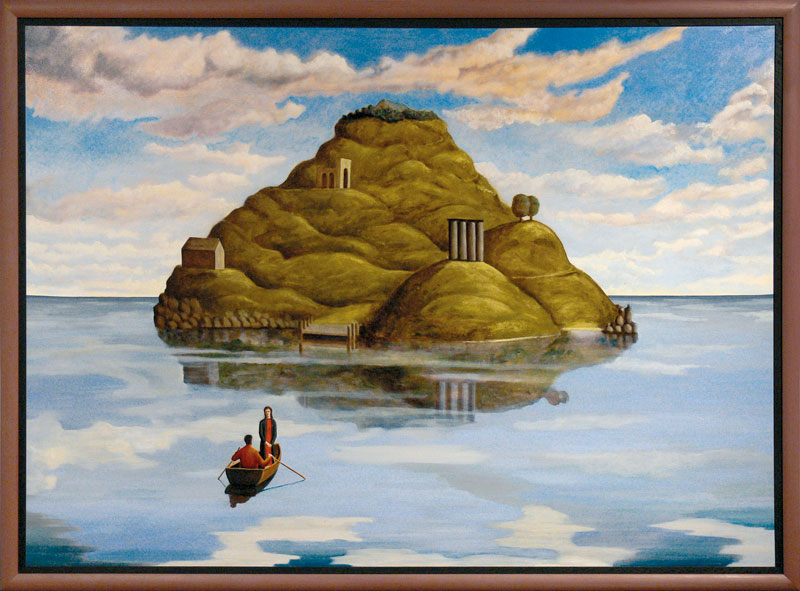

This timely retrospective of the work of David Keeling reveals, for the first time, the full range and depth of his art over forty years. This collection is also significant in that it demonstrates the fundamental shift that has driven his philosophical position since the mid 2000s. As I roam through the now familiar content and forms that characterise Keeling’s paintings, it becomes clear that the iconography has evolved to present an insistent and considered critique of who we are in this place and how Tasmania has been constructed as a landscape. The first work I encounter, Young Couple in a Developing Landscape with Panoramic Views (1988), is an easy read for anyone familiar with the history of eighteenth and nineteenth century painting, roughly corresponding to the period of Australian colonisation. A recapitulation of a Gainsborough’s Mr and Mrs Andrews, it buys into the English tradition of depicting the aristocratic landowner within their demesne.

This slippage across time and space surrounding colonialism and its many imports as an enculturation and ongoing “development” of the Tasmanian landscape has been Keeling’s persistent focus over many years. He would go on to explore these issues in many subsequent works. Plenty (1993) presents a table within the landscape of the Tasmanian midlands, furnished with a tablecloth of fancy lace and a selection of local produce as the available fare, including a bottle of wine. A possible companion piece for this work might be Early Morning (1996), in which two tables are set in a more developed rural landscape, their contents yet more refined and elegant, implying the ongoing imperative of the civilising impacts of colonialism.

Familiar elements within his iconography reappear frequently – the dead rabbit, the ringbarked, ghostly white trees, the table, laden or covered only in a tablecloth. The table will persist much longer (Two Tables at Water’s Edge, 2009), as the landscape itself becomes the dominant metaphor, marked by singular traces of human presence such as an abandoned bicycle in an otherwise deserted carpark (50 Minute Walk, Maria Island, 2006). These later images which curator Jane Stewart describes as “almost sublime” remain grounded by these evidentiary traces which act to strip out the purely romantic potential of the work and remind us of the pervasive, even insidious quality of our occupation of the landscape.

The Museum itself has provided the source for much of Keeling’s work, not simply for the trove of objects which he has re-framed in his paintings but also as a key component of his overall critique. This is central to works such as Nostalgia (1988), in which a museum display case sits in a bleak landscape containing an image of a man releasing a bird within a once pristine landscape. In Perfect World Forever (2001) another case contains an unspoiled landscape, and Still the Cunning Fox (2001) contains a fox within a landscape, the model for which was sourced from the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery’s own collection.

After two-hundred years of European settlement, the Midlands Keeling knows and travels frequently have suffered considerable damage from the imposition of farming methods unsuited to its fragile ecology, the developments as outcome of an “ownership” claimed by stealth, violence and the displacement of Tasmania’s original inhabitants. Amongst the now-dominant population, waste and profligacy have triumphed as the suburbs expand and their detritus accumulates.

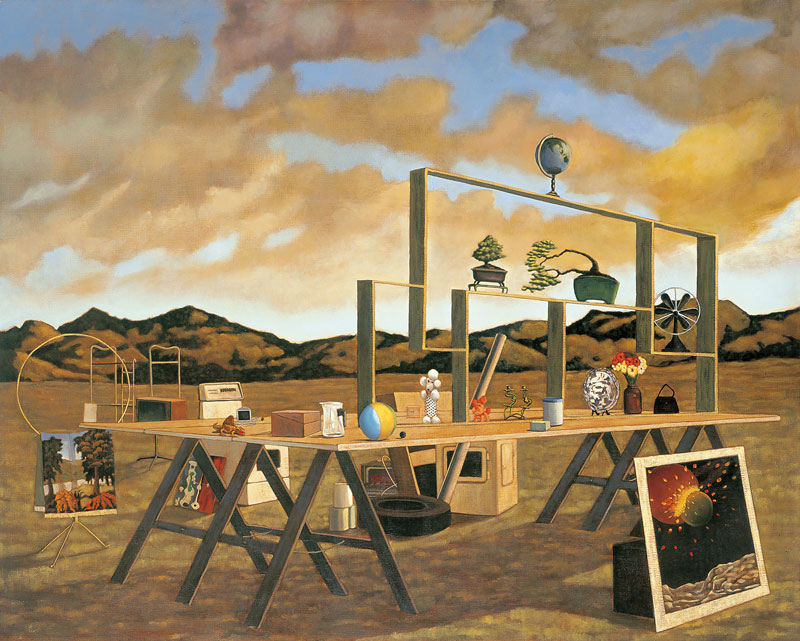

The evidence of this progression is presented in a powerful series of works from the early-to- mid 2000s. Keeling’s inspiration for this series was encountering a roadside stall of bric-a-brac castoffs, a mish-mash of consumer items spanning generations. Two Worlds Collide – Garage Sale (2000–01), Everything Must Go (2003), and Nick Cave with Steve Hart Dressed as a Girl (2008) typify this body of work, the latter enhanced by a bleak brown sky and distant suburbia signalling more excessive consumption and loss. These include objects from the artist’s own life, also referring to his past as a musician.

In all of these paintings the landscape is the central motif, often overtly theatrical like a backdrop. In the series of modernist interiors that follow the landscape appears as images seen through a “picture” window, such as New Room with Sought after View (2012). Here, the landscape is a framed view, a focus on a world outside and beyond the enclosed interior. These landscapes are simplified and idealised, much as the picturesque tradition might prioritise. Throughout his career the landscape has been central to Keeling’s vision but is not reducible to a singular function; rather, it has been a leitmotif performing many functions as it moved from signifier to signified to be more than symbolic, carrying the many subtleties of its various potential values, meanings and revelations.

Keeling has interpreted these values beyond the picture plane, in miniature groupings of the paintings as they are exhibited and installed in the museum context, as in his small sculptural constructions redolent of decorative vessel forms on elegant, hand-carved bases, and at scale in sculptural constructions such as Memorial Drive (2009) in which tree branches reminiscent of the dead trees in so many earlier landscapes now divide off to hold up what look like rear-view car mirrors featuring exquisite miniature landscapes based on snatches of views passed on the artist’s many drives north across the Midlands to Kelso, a favoured childhood holiday sanctuary and the primary site of his deep engagement with the phenomenology of the landscape.

Entry to the third gallery in this expansive exhibition is a revelation, both visually and psychologically. The area which forms the source of these extraordinary paintings is called Narawantapu in Palawa Kani, the language of the Tasmanian Aboriginal people, and is named after the national park extending along the North West coast of Tasmania with Kelso at its edge. The somewhat scrubby coastal vegetation of Sheoaks and Casuarinas synthesise the difference between any European tree and the rugged, windblown native species. Keeling has entered into their dense and overwhelming complexity as a perceptual encounter with their visual phenomena, captured through light. It is the light which ultimately reveals this sense of place, and identifiable experience as Tasmania (Lutruwita).

That Keeling should be returning to this place where he spent so much of his childhood is not simply nostalgia. There was a time when he was truly innocent, not yet aware of the contested history and the complex legacy of colonialism which would be his inheritance as a young man in a time of awakening. To come upon these places, so keenly evoked, in Narawntapu Close Up 2 (2008), and She Oak – Afternoon Light (The View from my Window), (2010–12) is to perhaps share with all those who can experience it, the fervent wish to close the gap dividing the past and present inhabitants of this land, through a shared love for this place and a deep penetration into the very fibre of it.

Perhaps this true immersion in place that Keeling’s work manifests for the viewer can only happen when the bigger picture, the stories and histories, the shameful events that occurred, can be absorbed, even transcended in this moment of perception. As a marker of this resonant phenomenology, in the artist’s own words, “I want my paintings to be almost cinematic and to absorb the viewer … so that they can be in the landscape … in that moment.”