There is a new vocabulary that permeates our everyday lives brought on by the pandemic. We are in unprecedented times, a one in one hundred years event, a challenging and difficult year and the time of the great pause. There is a sense of epic foreboding about this language, which attempts to describe and give name to this global upheaval and uncertainty.

The artworld has of course not been immune to the wide-reaching impacts of the shutdowns, the social distancing and the changes in how we work and socialise. A recent study by UNESCO and the International Council of Museums estimates that nearly ninety per cent of museums worldwide have closed temporarily and that thirteen per cent of those may never re-open.[1] These are sobering statistics which reflect the immense economic impact of the pandemic on the arts and cultural sector, resulting in loss of income, staff lay-offs and mounting debts. The closures expose how reliant the museum and gallery sector is on visitor numbers and physical attendances. Like theatres, galleries are social and connected spaces where the presence of audiences is essential to keep museums relevant and the front doors open.

For over twenty years now the internet has provided an alternative platform on which to reach audiences beyond the physical space. But for many museums and galleries the internet has remained an untapped resource, primarily used for marketing, program information and ticket sales. Some of the larger museums have provided online offerings through the Google Arts and Culture platform. Launched in 2011, “virtual” tours are offered through the galleries of the Musée d’Orsay, Uffizi Gallery, J. Paul Getty Museum and more. Whilst the platform allows audiences to browse collections from their couches, the experience is like a Google Street view for museums. Browse and click, go left, go right, zoom in, zoom out and move on quickly with the aim of replicating a museum experience rather than exploring the internet as a medium for the creation of art.

While the sector could hardly have predicted let alone prepared for this pandemic, it is those galleries and museums which have embraced the digital that remain active and accessible in these times of shutdown. These are the spaces that have adapted quickly to the conditions of the pandemic and are not only reaching audiences but are supporting artists through new commissions, workshops and programs.

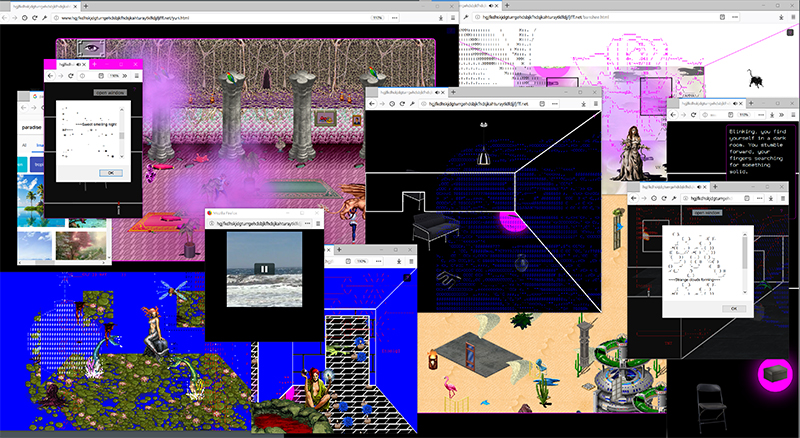

The New Museum in New York has long-championed the internet as a way to connect to audiences but has also actively curated work in the online space. The Rhizome project based at the museum describes itself as “the leading art organization dedicated to born-digital art and culture. Founded in 1996, affiliated with the New Museum since 2003, and an anchor tenant of NEW INC, the first museum-led incubator, since 2014, Rhizome has played an integral role in the history, definition, and proliferation of art engaged with networked technologies.”[2] Rhizome has been at the forefront for over 25 years of commissioning, curating and archiving contemporary digital artworks. Its association with the New Museum has ensured that artists working in this space are supported, exhibited and even collected.

In turn, the New Museum is well placed to ride the temporary closures, as it has an established and active online identity. Visitors to the New Museum website are invited immediately to engage with the digital program New Museum Now featuring artist talks, virtual tours and video previews. A highlight of the New Museum Now program is “Bedtime Stories” initiated by the artist Maurizio Cattelan, who envisaged the stories as a way of staying together during times of isolation. Thanks to Cattelan, falling asleep is a delight with stories read by Iggy Pop, Tacita Dean, Joan Jonas, David Byrne and more. Artworks created for the online space and other formats are also available including Intern Purgatory, a Mobile VR work created by Tough Guy Mountain, and Screen Talk a prescient 2014 web-based mini-series that depicts a world afflicted by a major pandemic. These works, freed from the physical space of the museum, explore how art might be experienced outside of the museum via the connectivity that is now so entrenched in everyday life.

There is a wealth of art that has been created for the online, mobile and virtual space over the last 20 years and many artists are continuing to work and create in this space. In Australia, most museums and galleries have been slow to embrace online and mobile platforms as a site for the production of artwork. These kinds of works are more likely to be available through screen festivals and networked media industry events, such as the recent “Electric Dreams” conference and festival of immersive storytelling held as part of the 2020 Adelaide Fringe.

The Australian Centre for the Moving Image in Melbourne has predominantly moved to online programming due to its temporary closure for redevelopment. The ACMI website invites audiences to “a program of virtual screenings, online resources for parents and teachers, skills workshops led by industry professionals, talks, retrospectives and more, all from the comfort of your home.”[3]Audiences can engage with weekly talks, workshops and watch films in the Virtual Cinémathèque program. While there are currently no artworks available for viewing on the ACMI website, the Re/New of ACMI will continue to commission and exhibit work for artists in the interactive and VR spaces.

It is of course disheartening to see the sector-wide closure of many exhibitions that have seen countless hours of planning and curation, from artist run spaces to our state galleries and museums. Director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Michael Brand, calls these “ghost exhibitions.” “After rigorous curating and, especially in the case of major international projects, extraordinary feats of diplomacy and logistical planning, these new exhibitions are now moored in their beautifully designed spaces lacking only one thing: an audience.”[4]

Whilst the AGNSW remained closed from April to June and the exhibits sat in the silence, the gallery created some virtual noise by welcoming artists, musicians, writers and performers into the space for audiences online through the launch of “Together in Art”. Effectively and rapidly implemented, this dedicated online site provides access to artists, events and ideas during the COVID-19 shutdown and will continue on post COVID. What stands out about this program is that AGNSW has supported artists to present work during the lockdown in order to stay connected and even build new audiences. A series of videos chronicle particular days of the closure, where artists, perform or sing in the empty gallery spaces.

The first of these video performances on day six of the closure sees the soul singer Ngaiire, perform “Fall into my Arms”.[5] Her voice resonates and echos along the empty halls and corridors, providing an enigmatic and even haunting experience of the ghost exhibitions. On day 28 of the closure the performance artist Maissa Alameddine stands against a painting by Lesley Dumbrell. She sings “Hal Asmar el Lon”,[6] a traditional Arabic song about yearning for the beloved, it is a compelling simple performance which can be watched and listened to over and over again.

The most recent offering from AGNSW is Hyper-linked,[7] billed as an exhibition in the digital realm by seven contemporary Australian artists. Curated by Isobel Parker Philip, and launched at the end of July, this is perhaps one of the first exhibitions by a state gallery in Australia that has been commissioned solely for the internet. The exhibition featuring work by NSW-based artists Heath Franco, Brian Fuata, Matthew Griffin, Amrita Hepi, Kate Mitchell, J. D. Reforma and Justene Williams is a mixture of video and interactive works that examine the role of the internet and the networked self.

As part of “Together in Art” Blue Mountains-based artist Adrienne Doig was invited to present an online workshop for young people. Doig says, “I received an email asking me for ideas and I immediately thought of fuzzy felt.” She also decided to put her vast collection of toilet paper rolls to use. “What a great tie in to COVID-19, with the panic-buying of toilet paper. So I suggested I could teach viewers how to make a toilet paper roll doll self-portrait.” Doig’s workshop idea was embraced along with several other inspired offerings including “How to make a collage portrait with Deborah Kelly” and “How to make a dada poem with Tony Albert and Bree.” Doig also posted the workshop on Facebook and the concept took off as a fun lockdown activity, with many of her friends and followers creating their own TP roll self-portraits.

As for many artists, the pandemic has had a significant impact on Doig. Her exhibition Picture Me at Martin Browne Gallery was re-scheduled to August and a survey exhibition at Bathurst Regional Gallery scheduled for July was postponed until December. Her partner became ill and Doig says about this time, “I’ve kept busy making work and lockdown has been quite productive. I’ve always found making art soothing, so I would go to the hospital with my embroidery and sew while visiting.” She adds, “If you think about COVID too much it becomes overwhelming, by continuing to make work I can maintain a sense of continuity and normalcy.” Doig says she has also spent a lot of time on Instagram, following artists’ COVID projects and galleries. She says, “This has changed the idea of what a gallery is, it’s taking the gallery to the people. It’s opened up the AGNSW, you can see who the people are behind the scenes.”

It is a prescient observation from Doig that COVID is potentially changing what a gallery is and how galleries reach their audiences. The pandemic has jolted galleries and museums into thinking beyond the physical venue and being more creative with promoting access to programs and collections. A popular COVID iso-project has been the call from several museums to recreate artworks from their collections, using the domestic objects and materials at hand. As Adelaide-based artist Melinda Rackham points out, it is a call to reinterpret works by “the masters” held in museums across the world. Scrolling through the popular Instagram account @tussenkunstenquarantaine, it is Vermeer, Van Gogh and Dali that are appearing in these lighthearted tableaus made from cushions, vacuum cleaners, brooms and other domestic items.

Rackham is currently collaborating with Elvis Richardson as co-author on the soon to be released CoUNTess: Spoiling Illusions Since 2008. A timely publication, it is described as, “A heady mix of rigorous research, harrowing and humorous blog rants, hard-crunched data, theoretical musings, intimate revelations and visual art works.”[8] Rackham is compelled by the statistics around the acquisition and exhibition of women’s art and concerned that projects like @tussenkunstenquarantaine encourage the exclusive veneration of male artists.

Early on in the pandemic Rackham was given a silver Barina. Wanting to show Richardson her new car, she recreated Found Paints Lane, the well-known 1996 work by Richardson of a found photo from 1966 of a woman in a bikini standing by a Mini. It was a joke at first, with Rackham wearing an old pair of bikinis and adopting the same pose. But this bit of fun sparked an idea in Rackham: “Why copy tired old masters when you can remake contemporary Australian mistresses?” And the #remakemistresse project was born.

Rackham has now re-interpreted almost 30 artworks by Jenny Watson, rea, Rosemary Laing, Julie Rrap, Emma Hack, Fiona Hall, VNS Matrix and others. She says, “I made them with everything from home, I didn’t buy anything. The Copyright Agency granted me a small amount of funding to cover just a few, but I can’t stop making them and I think I will make 50 by Christmas.” There are many layers to #remakemistresses and Rackham is pleased with the response, contributing to feminist ideas about parody, incorporating the “fun” alongwith the “sensible politic behind it.” The complete set of images are exhibited online during this year’s South Australian Living Artists Festival (SALA) throughout August.

Viewing exhibitions and artworks online will undoubtedly continue as a new reality for artists, the artworld and audiences. With limits on travel and continued social distancing, it may be many months or even years till people can gather in pre-COVID numbers at galleries and museums. Across Australia artist run spaces, commercial galleries and the contemporary art gallery sector have all been impacted. Some have closed their doors and for some that could be permanently, and others have moved to online exhibitions, online sales and social media projects.

For ACE Open in Adelaide an exhibition of videos curated by Olivia Koh scheduled for exhibition from May was instead presented online. The irony not lost on Koh was that the exhibition recess presents was originally conceived as a physical manifestation of the online video portal recess.net.au, launched in 2016. As an exhibition originally intended to embrace the physicality of the gallery, “for viewers to be bodies together in space, experiencing moving image works as a curated whole,” the return to an online presentation prompted a new approach through their staggered release, contributing to the conversation around video art. The recess site is a welcome initiative and especially in the time of COVID provides a platform to stay connected. Koh writes “As one work is phased out another appears, so that the sequenced works inform each other like a string of sentences, or a body spinning in the landscape – a collection of meanings that are not definitive but always on the move.”[9]

Watching video art at home on small and personal screens is pleasurable and convenient. It can be watched any time, rewound and watched again. There is a delight in seeing work that is transformative and transportive like Tout en sollicitant le soleil (cupola 1/2), 2012 by Paul Maheke. Standing along in an open space with a backdrop of trees and hills, performer Francis Beaumont Deslauriers in a twirly skirt of glittery material spins for several minutes.

The performance invokes a whirling dervish set against a bucolic backdrop in a play of shadow and sunlight. The only sound is a breeze through the grass and the hum of crickets. As an antidote to isolation, Koh’s selection of Tout en sollicitant le soleil (cupola 1/2) seems perfect for aloneness, as it is a solo performance speaking to the power of repetition, meditation and silence. It is a work that provides solace, an antidote to isolation, in synch with the slowing down of everyday life.

Also closing its doors for COVID was Monster Theatres, the 2020 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art curated by Leigh Robb. Like AGNSW, the Art Gallery of South Australia developed an online program which provided access to the exhibition through workshops and videos. AGSA also provided financial support to local artists through the South Australian Artists Fund, with artists affected by the COVID shutdown invited to apply for bursaries of up to $10,000 supported by AGSA’s philanthropic community.

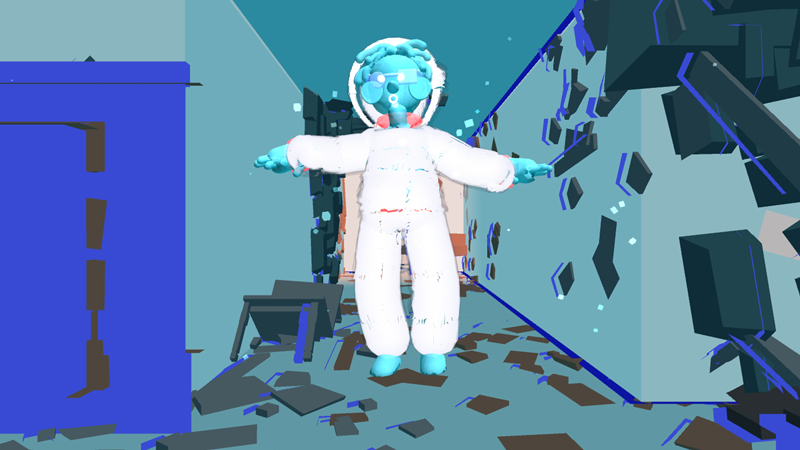

Perhaps the most prescient work in Monster Theatres is Reclining Stickman by performance artist Stelarc, who has often integrated an online experience in his artworks. This major new work commissioned for the Adelaide Biennial further extends Stelarc’s interest in the relationship between the human and robotic body. He describes it as “Literally, a monstrously amplified stick figure made of aluminium using pneumatic rubber muscles. There are sounds of compressed air, muscles expanding and compressing, exhausting and extending, which represent the anatomical bending of the limbs.” The Reclining Stickman can be controlled and moved in several ways, either by Stelarc performing with it, by the audience in the gallery via a control panel and online through an interactive web interface. Stelarc has created the almost perfect conditions for a COVID artwork, an autonomous work that can still remain operational and interactive during the gallery closure.

Artists like Stelarc and Melinda Rackham are deft at creating digital, electronic, screen-based interactive experiences, having worked in media arts for many years to navigate the relationship between the virtual and the physical world to extort a bolder message. It is time for our cultural institutions to listen to, learn from and support such innovations as new forms of cultural adaptation. Unprecedented times call for new ways of creating, exhibiting and experiencing artworks. In a post-COVID world it is artists who will lead and determine what a gallery of the future could be. They have already pioneered beyond the gallery walls and have seen a future that is connected, distributed and possible.

Footnotes

- ^ “13% of Museums Worldwide May Close Permanently Due to COVID-19, Studies Say,” Hyperallergic, 20 May 2020.

- ^ See the New Museum’s Rhizome sub-site: newmuseum.org/pages/view/rhizome.

- ^ See the home page at acmi.net.au.

- ^ Michael Brand, “Art Stuff” blog, 16 April 2020.

- ^ “Ngaiire: Fall into my Arms,” Together in Art, Art Gallery of New South Wales, 3 April 2020.

- ^ Maissa Alameddine, Together in Art, Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2 May 2020.

- ^ Hyper-linked, Together in Art, Art Gallery of New South Wales.

- ^ CoUNTess, The Book. Due for release mid 2020.[https://www.elvisrichardson.com/countess-book.html]

- ^ Ace Open, recess presents: 8 May – 17 July 2020.