As Australia’s “biggest and most democratic arts festival” SALA, the South Australian Living Artists Festival, abjures the regular filters of the curator or artistic director to forefront a more community-driven recognition of the work of South Australian visual artists. The surge of interest is palpable, judged by the unusually high attendance figures reported across the regular venues for contemporary art as well as those that infiltrate the rooms and corridors of many other public, institutional and private venues, such as libraries, bars and cafes that sport the familiar SALA logo on their frontage.

As a tribute to outgoing CEO Penny Griggs and her team it seems that everyone has a stake in SALA, driving the momentum of one of the few festivals in South Australia that is unashamedly and strictly local, even if the work of many of the key artists profiled enjoy much broader public recognition outside of the state. It is also not just about the new but gives especial recognition to those who’ve been in it for the long haul, and in a more indirect way what it means to be an artist living and working in South Australia. I was reminded of this when sampling a few of the highlights in key venues for contemporary art in Adelaide that gave artists the opportunity to present works of ambition and scale.

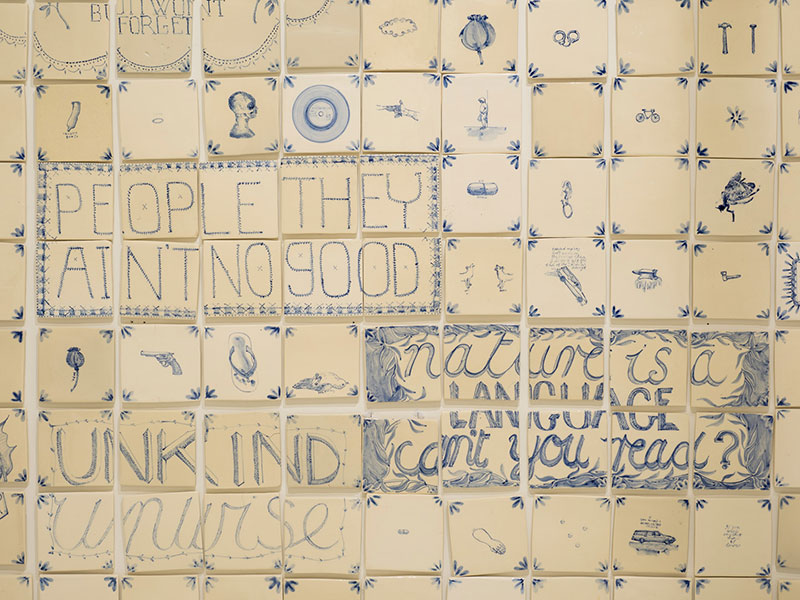

Representing ideas of practice relevant to the embattled home front, Gerry Wedd’s exhibition at ACE Open, Songs for a Room tackles the domestic challenges head on. Just last week this striking installation of ceramic ware was awarded the 2018 Don Dunstan Award for artists whose work explores social justice themes in alignment with the priorities of the Don Dunstan Foundation, including homelessness, mental health, migration and economic empowerment for those on the margins of society. Wedd was the 2016 SALA Festival Jam Factory icon and his extraordinary collection of ceramic work Kitchen Man is still touring nationally. This new presentation of work has moved from the home as the hearth (as in the Kitschen) to a place that might more fittingly be described as the outhouse or washhouse for the indigent and homeless.

Wedd’s title, Songs for a Room, and the artists own recommended selection of texts and music tracks, places his brand of socialism atop an age-old folk popular cultural tradition of narrative and message-laden decorative arts, not unlike the UK’s more famous Grayson Perry, whose trajectory (coming out of a background in the more conceptually hierarchical fine arts) Wedd notably shares, placing the emphasis clearly on the relational, social enterprise of the work. This is brought home by the promotion that 50% of proceeds from the sales of the individual tiles, platters and vessels are to be donated to the Adelaide Day Centre for Homeless Persons.

To make his case the usual flowers, shepherdesses and children are replaced with (mostly male) rough sleepers, references to drug use and ennui in which “chaos rules,” “people they ain’t no good,” “finders keepers”, “losers weepers” etc. As Wedd states in the decorative broadsheet that functions as the artist statement, “This is a playful nod to Delft tile painters of the 1600s who would sneak subversive images of people smoking and weeping in amongst traditional scenes of tulips and windmills.”

In an inspired parallel presentation of work at ACE Open, sharing the space with Wedd’s Songs as another room within a room, Julia McInerney’s The Garden, the annual ACE Open artist’s commission, is an installation of wall-to-wall unfixed, hand-cast cement pavers and other works that the visitor is invited to enter and gently tread upon. Walking the tiles to feel their presence slightly shifting and clinking underfoot supports the theatrical space of minimalism as an interface for a more pared back formal enquiry and revelations aligned with a more urban architecture of thought. Spelled out by the detail in the labels of the accompanying framed and placed objects, photographs and text works, literally coming out of the concrete and woodwork, this work derives from a mindful accumulation of references points that support the cultivation of an urban garden.

Beginning with the receipt of a package from the West of Ireland, containing apple seeds (and the breaking of “The Law” by their stealth of passage into the country from the West of Ireland within the leaves of a tea bag), this work is a form of sculptural prose as working process. The collection and germination of the seeds and the central motif of the apple, further captured in the core-sampled railings from the felled wood of an old tree in South Australia and the accompanying photographic observations on a grey scale, presents a very “German” post-industrial and porous aesthetic (aligned with a reference in the wall text to the modernist poetics of Walter Benjamin). Like Wedd’s social jibe, this is not without a more confronting edge and aporia of loss and regeneration in reference to the Christian “Fall.”

As in previous work, McInerney slows down the experiential underpinnings of her sculptural practice to look at form as generative, supported by various personal and literary anecdotes. Her own writing in the catalogue denotes this presence of the text in daily life as an inheritance of Walter Benjamin’s mobile aesthetic of the literary flaneur. The public readings from selected works of literature and a guided walk to a local community garden where we were given delicious apples to eat reinforced this poetics of presence as a leap of literary faith. These were the aptly named “Footnotes” to what otherwise is open to the viewer to “seed” and interpret through the works on view in the exhibition.

(1).jpg)

Like the transient moments in the sampled texts by dead writers (Jane Bowles, Marguerite Duras and others) two photographs, Fall I and Fall II, as the sectioned limb of the apple tree reminded me of those canonical twentieth-century photographs by Eli Lotar from 1929 of the hoofs of slaughtered cows lined up on the cobbled streets outside a slaughterhouse in Paris, cited by Georges Batailles as an example of our descent into base materialism. In this case, the formlessness of raw matter is no longer a ploy to invoke rude horror; but, rather, a gentle task of mourning that is more like Proust’s memories of the past.

Continuing this primal engagement with art history as a form of the vanitas (still or transient life), Aldo Iacobelli’s Conversation with Jheronimus on exhibition in the Anne & Gordon Samstag Museum of Art is a further tribute to a European sensibility by an artist who migrated to South Australia from Naples as a teenager, and whose practice is aligned with arte povera. For this ambitious installation, based on the artist’s recent encounter with the works of Jheronimus Bosch at the Museo del Prado, the reference is a more direct tribute to a worldview laden with mystical and humanist metaphor in representations of the material world.

The centrepiece of this installation, an apparently life-size model of the hay wagon from The Haywain Triptych (c. 1512–16) in the Museo Nacional del Prado, is a grand folly that supports the overwhelming presence of this symbolic register and leap of faith in Iacobelli’s imagined conversations with Bosch through the master painter’s works and recorded observations. As Maria Zagala notes in the online catalogue essay, Iacobelli has frequently cited Bosch’s observations in connection with his works, including one that is clearly relevant here: “The Woods Have Ears, the Fields Have Eyes.”

This work is laden with a wry anthropomorphism as a kind of monumental thanksgiving and reflection upon the European inheritance of the settler values of the pioneer. Resolutely immobile (and clearly hollow) the hay cart is like a child’s toy. Only a Romantic (like William Morris and the Pre-Raphaelites before him) would try to make sense of this agri-rural economy and lifestyle, as an expansion of an arcane, even mediaeval world of mysticism and self-reflection, as applied to the very altered landscape of the present times. But Iacobelli makes the connection through the more recent struggles of the figure of the refugee in accompanying graphic works, doubling his own migrant experience and introduction to a new land.

Flanking The Cart as the major companion piece is a triptych, a series of three large panels of pulped newsprint, porous and malleable like the tilled and cultivated earth itself and featuring obvious hand and finger prints, presented hanging on metal hooks (like a meat hook or those used to tug hay bales). Surrounding The Cart, a bevy of trollies carry bitumen-clad clusters of victuals, body parts, animal and human figures, agricultural implements and clearly blighted potatoes are a reminder of the horror and fascination embedded in the details of Bosch’s paintings.

Filling the frame of this vast repertoire of images and form-filled dialogue is the sense that this entire installation represents a kind of morality or passion play doubling the world of Jheronimus Bosch. As an update on these historical dilemmas of the soul, it helps to know that the pulp paper triptych is made from the fake news published by The Adelaide Advertiser. The presence of such a glut of industrial petroleum by-products across the many smaller sculptural works and effigies is also like the liquid mire of those scenes of grotesque figures in hell.

Coming full circle to the symbolism of the hay, as Zagala explains in the accompanying catalogue, the origin of The Haywain may have been inspired by the Flemish proverb “The world is a haystack and each man plucks from it what he can.” Greed, gluttony, excess and bundles of nostalgia and regret are clearly symptoms familiar to the mediaeval artist and patron not dissimilar to our own fears about where it is all heading. And it doesn’t look good.