Campbelltown Arts Centre has once again trumped the more august cultural institutions of Sydney’s CBD to host a candid and timely exhibition. Curated by David Capra, Sheer Fantasy brings together fourteen Australian and international artists who reference super-saturated popular culture with a cloying mixture of lurid love, cynicism and foreboding. There is also a lot of wit. Capra came to the notion of the exhibition after being surprised at how moved he was after watching a YouTube clip of the 1990 funeral for puppeteer Jim Henson where Big Bird sings “It’s not easy being green.” Perhaps the clip took the curator back to a childhood where Santa was once real. The recognition that such loved figures are actually false constructs made by trusted authority figures can be deeply shocking. The continued faithful ascription to fantasy into adulthood is viewed negatively, a wrong-headed wilful retreat to infantilism.

I really like the title of this exhibition. Strangely old fashioned, the emphasis on the “sheer” is both transparent and extreme, vertiginous even dangerous. Way back before personal devices and meta-data, before keyboards, multi-screen platforms, coding and tablets there were clearer boundaries between what constituted fantasy and its relationship to consensual reality. In modernist paradigms fantasy was allowed for and encouraged in children and adolescents. Bedfellows to the imagination and to dreams, fantasy was once a private affair mostly referenced by artists and other cultural workers. There was a certain luxurious cachet that fantasies were so intimate to have no “true” or “real” function except as a form of expiation for the individual as fantasist. When necessary fantasies could be revealed at “an appropriate time and place”—in the cinema, books, the doctors surgery, the dining room table, the art gallery and the bedroom. Now everything is inexorably public and accessible. Wi-Fi driven illusions of connectedness support a mindset in which one can no longer justify a private life. We must always be ON.

Sheer Fantasy is part Nanny State admonition about reckless behaviours and irrelevant thought patterns and part Sleaze Bag Invitation, a tacky commercial overlay suggestive of sex aids from the last century. Indeed, one of the key energies of Sheer Magic is a sense of an almost pathological excess, over-identification, over-sharing and self-projection. Capra’s artists suggest that we have no immunity from mass obsessive compulsive disorder. This new type of OCD is a symptom of human over-investment in the photographic image. Sigmund Freud predicted that, apart from the shared facts of our birth and inevitable death, there are two things that links us all—shopping and scopophilia. As image fetishists, our desires will not be sated.

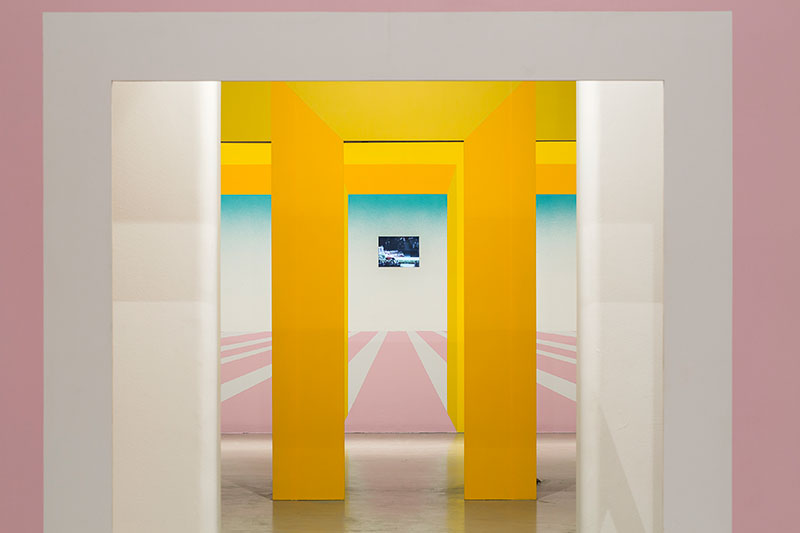

The design studio 1000BCE, based in New York, were commissioned to produce lurid trompe l’oeil painted sets, plinths, curtains and a mural to give the gallery spaces a simultaneously “ancient, theatrical and strange” quality, as it states in the exhibition catalogue. Obviously false constructs, on one side propped up with armatures and sand bags, the other side is carefully painted with perspectival illusions reminiscent of those 1970s illustrations of a newly built exact and pristine Stonehenge. Here the viewer journeys into a type of twenty-first century Barrow Grave, with mysterious darkened spaces, a skewed jumble of portals and thresholds. There are plinths like altars. Esme Timbery’s Untitled (Sydney Opera House),2002, looks more magnificent than ever before, gloriously isolated on high on an over-scaled raiser.

The UFO & Paranormal Research Society of Australia has been given an epically scaled workstation as a museum-style display of memorabilia to support a faith in the existence of Extra Terrestrials and their ongoing contact with human kind. Representatives of this society inhabit the gallery space for the duration of the show. Nearby, the glitter of Pat Larter’s late work dissolves form and content to return everything to the infinite realms of quantum physics and the primordial stew.

In contrast, hidden like reliquaries the viewer happens upon tiny monitors to encounter mysteries such as the aforementioned Big Bird clip or an astounding quasi-symbolist memory painting by film actor and artist Kim Novak. Vertigo/ Vortex of Delusion is a multi-layered portrait of the 1958 film Vertigo. The detailed and complex composition features Novak’s character Madelaine Elster and Carlotta, her doppelganger from the nineteenth century, the Golden Gate Bridge, Alfred Hitchcock, Jimmy Stewart emerging from swirling folds and tendrils of mist. Your head will spin more once you realise the subliminal soundscape of the exhibition is the insidiously hypnotic “Carlotta’s Portrait” theme by composer Bernard Herrmann. It is only recently that Kim Novak made public that she is bipolar which adds a certain poignancy to the work.

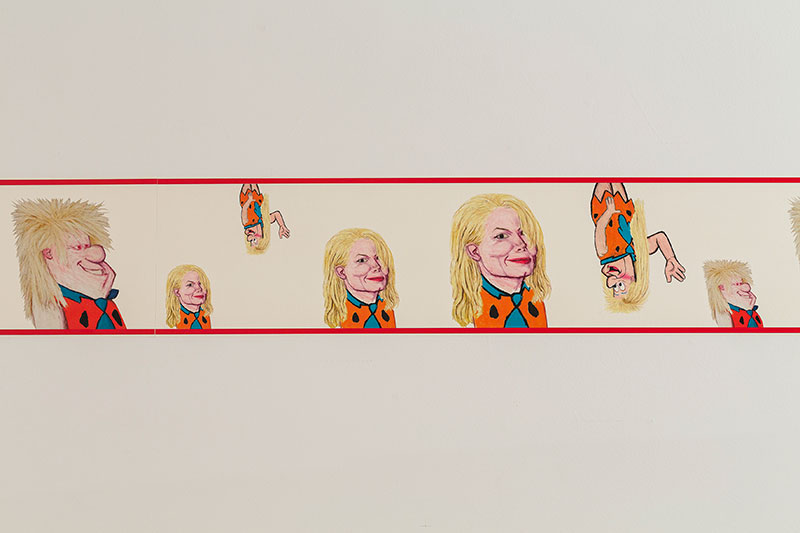

Terri Bowden presents a wallpaper frieze, Untitled, 2018, that depicts two versions of Fred Flintstone sporting impressive mullets and a disarmingly creamy blonde Michael Jackson complete with curling carmine lips and those caught-in-the-headlights eyes. Formally, the disjunct of modes of representation—combining one rendered more illusionistic than the other, with the flat and then chunky paint application—operates like 35-mm film stock or a ribbon winding around the spaces to force a conceptual union of the seemingly disparate works on display.

Commissioned by Campbelltown Arts Centre. Photo: Document Photography

In this ocular regime William Wegman’s Spelling Lesson (1973–4) where the artist teaches the English alphabet to his pet dog, Man Ray, or in portraits such as Tote and Eyewear (2001) depicting one or more of Man Ray’s fourteen progeny in costume posing as humans, are frankly disturbing. They are not just funny and illogical but in this context render cute anthropomorphism in a much darker and creepier hue. The unquiet aspect of familiar relations is underlined again by “Coral” (2016) a giant stainless-steel homage to kitsch domestic ornament by Michael Parekowhai. Here the idea of ornament as a type of topological snare (see Arthur Gell) is made clear. The hyperbolised scale, the gleaming reflective surfaces and the suburban Axminster carpet plinth further disrupt the domestic meaning/contexts of the original object to make the Feminine subject dangerous.

Vision and meaning are destabilised again by Polly Borland’s lenticular photograph Bunny and Louie (2018) which superimposes a 2016 image of the artists son with a photograph from 2004 of Gwendoline Christie. one of Borland’s favourite models. The crinkle-cut or concertina surface creates an oscillating depth of field. This is a technique that harks back to the heyday of the Wunderkammer and the notion of the artist as virtuosic magician. It is significant that the freakishly tall Gwendoline Christie is also a skilled actor, talents recently etched into the public consciousness with her gender-neutral portrayal of the warrior Brienne of Tarth in the HBO neo-medieval fantasy saga Game of Thrones.

I found it odd that the curator sidelined the most politicised works in the exhibition. Archie Moore’s wall drawing of Super Powerless Man is overloaded with masculine signifiers—big guns, blades emerging from ankles, toes, knees and nipples, giant batwings, the hunched looming pose and Schwarzenegger-style figure and stance here laughable, excess to requirements. The work also stands as a guardian to the Mother of Pearl 2018 triptych by Raquel Caballero. A riot of sewn appliqued imitation velvet, lace, lycra and lame, these are moralising banners where rock and roll agents of good and evil—aka Rolf Harris, Mick Jagger, Prince, Lou Reed—meet Donald Trump and the stairway to heaven. Caballero adopts machine and handmade unorthodox crazy quilting and embroidery styles to make one of the highlights of the exhibition.

.jpg)

The amount of space given to a cinemascope style painted set of Monument Valley to frame Hello Stranger, a performance work by Mark Shorter also seemed excessive. Over the last five years Shorter has gained public and critical notice for his use of avatars to examine what can be loosely termed the compounding failures of gendered masculinity. Vehicles like Schleimgurgeln (part Robert Crumb chicken man, crossed with a blind Benjamin HD Buchloh-type art historian), the self-explanatory Antipodysseus or Tino La Bamba (a composite of hopelessness and bravado drawn from Cervantes Don Quixote and its documentation) are at times visually compelling. But Renny Kodgers, the avatar that inhabits Hello Stranger is for me the least successful of Shorter’s avatars. Shorter does not demonstrate a sophisticated understanding of the cultural context that is the target of his critique, in this case country and western music and Kenny Rogers.

He takes the easy path of grotesque parody of the “Take me home” variety–pure and simple, truth love and goodness at the heart of the genre. I am certainly not a dyed-in-the wool-fan of C&W but the heritage of artists like Huddie William Leadbetter, Hank Williams, Elvis Presley, Dolly Parton, Loretta Lyn and Johnny Cash with their finely honed roll-with-the-punches fatalism has an honesty and pathos that deserves more respect. Here in this Monument Valley there is a truck driving out of the valley into the darkness. Members of the public could sign up to be a passenger with Renny Kodgers for a 20 minute performance. Having once been a hitch hiker for about ten years I did not need to take that trip down memory lane. Hello Stranger was an elaborate invitation to endure the dubious pleasure of being trapped in a cabin with an odious character travelling into the night from nowhere to nowhere. This is fantasy at its most nihilist.

Commissioned by Campbelltown Arts Centre. Photo: Document Photography

Near Shorter’s work is a model village from the Casula Powerhouse Collection. Set high and glowing on another plinth this is not some dreary re- presentation of Englishness, rather this small town beckons a new future where there is no poverty only the perfection of light to clear the darkness. Made by Javier Lara-Gomez (d. 1997) there are echoes of the work of Bodys Isek Kingelez (1948–2015) in the clean bright lines and colours of the found materials that enhance the fantastic qualities of the architectural maquettes. Unlike Kingelez, a free citizen of Zaire/Democratic Republic of Congo who made his art brimming with the possibilities of a postcolonial epoch, Lara-Gomez completed these works in his cell while a prisoner in Long Bay Goal.

Lara-Gomez transformed unwanted materials deemed safe by the authorities—old venetian blinds, obsolete electronic parts, cardboard, plastic food containers and utensils, bread ties, glossy catalogues—into vital admixtures of domestic houses, villas, palaces, theatres, churches chapels, recital halls and foyers and cocktail bars. Imprisoned for his part in the largest importation of cocaine into Australia, Lara Gomez quite possibly experienced or had within his grasp the worlds of luxury his architectural models reference. Put simply, these works are talismans of the “outside”, the colours and rhythmic decoration are defiantly un-Australian and speak of the memories of Family, Community and Country as well as the triumphant fantasies and innate escapism of immediate pleasures underpinned by great wealth. These works as poetic tragic follies should be on permanent display.

Sheer Fantasy cleverly captures some aspects of the prevailing Zeitgeist in which the Fake or the Not Real, the constructions of Truth, the processes of Deceit and the Lie are the key realities or concepts du jour. But in this intelligent exhibition David Capra’s fourteen artists propose that fantasy is an ambivalent symptom of current media fetishism an often problematic deception, the flight from the real remains a Romantic gesture, an ultimately liberating survival strategy.

.jpg)