When missionaries arrived in Southeast Asia and Oceania in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries they created massive and permanent change. Their aim was to wean the Indigenous populations from traditional customs and introduce them to “civilised” ways. The naked would be clothed, the wanderer housed and the word of God taught. A recent exhibition curated by Joanna Barrkman for the Charles Darwin University Art Gallery in Darwin documents some of those changes with a display of 67 wooden sculptures from the Timor-Leste Island of Ataúro.

Ataúro Island is 36 kilometres from the Timor-Leste capital of Dili. Despite Ataúro’s relative isolation, the island did not escape the brutal impact of modern regimes: for centuries the Dutch and Portuguese fought for control, the Japanese and Indonesians invaded, and the Christian Church (both Protestant and Catholic) attempted to suppress Timorese animist beliefs. The arrival of Dutch Calvanists in the 1930s brought radical and irrevocable change to the Indigenous populations. Ancient religions were assimilated into Christian beliefs and traditional practices altered. Ephemeral renditions of religious icons and ancestors were now being produced on materials designed for sale while certain contentious depictions were either banned or manipulated to suit Christian doctrine.

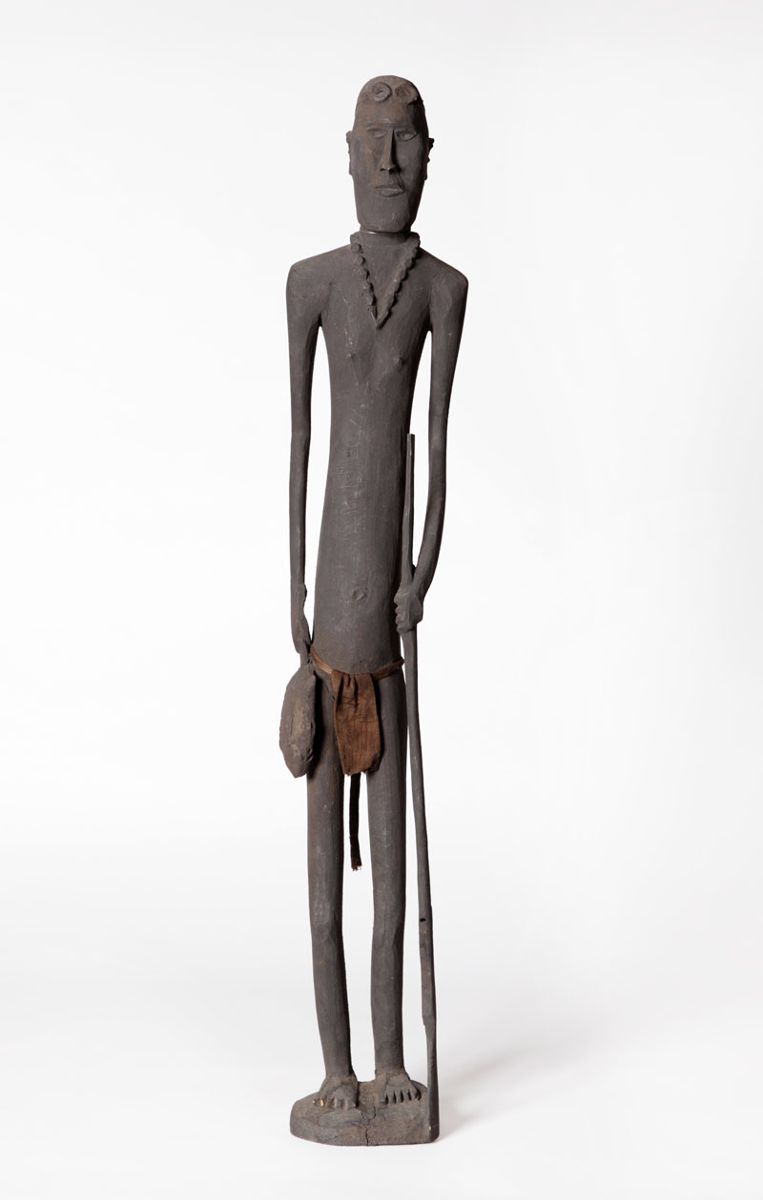

The exhibition reflects those changes in several of the sculptures. Pre-Christian figures have uniform patina over the entire body indicating no use of apparel but after the arrival of Christianity, fabric was used to cover the genitalia of the carvings. Other examples of Christian influence can be seen in one of two video projections. The videos provide an important tool connecting the sculptures on display to religious and social practice on Ataúro Island. Padre Xico (a priest in Ataúro) explains in Ro'o Putin Hatin – The Boat from Putin’s Place, “Saint Peter was seen as the model fisherman, the fisherman who followed the path of Jesus. Jesus invited fishermen, as a profession that Jesus watched, so this was inserted into the Makili culture as something special, as something special from God who looked over our culture.”[1]

In Australia parallels can be seen with the arrival of missionaries in the eighteenth century. Indigenous Australians began to alter their practices of worship to include Christian iconography. An exhibition held at the Australian Catholic University's McGlade Gallery in Strathfield, New South Wales, in 2013, also explored the melding of Aboriginal and Christian spirituality. A key work was a statue by George Mung Mung (c. 1921–1991) titled Mary of Warmun. Mung Mung was a traditional Gija man from the Kimberley community of Warmun in Western Australia. Mung Mung created the sculpture to replace a Virgin Mary statue broken at a local school. It has become a symbol of harmony for both the Catholic Church and the Gija people.

The early artists of Ataúro Island carved the figures to transubstantiate the spiritual into the physical for rituals venerating ancestors. When “not in use they were strung over a rafter with the use of handmade twine, twined or plaited from palm leaves”, as Barrkman explains in the accompanying catalogue. Occasionally they were inserted on a stake at the entrance of ceremonial houses to act as “a site or alter for offerings and sacrifices to invoke rain to ensure good harvests”.[2] To encourage the ways of God, missionaries began the systematic banning of many traditional practices. During the 1970s the Protestant church forebode Ataúroan figurative carving that resembled any form of ancestral worship.

Carvings that eluded the Protestants were hidden by the Islanders in secret caves. In 2005, members of the Ataúroan community retrieved the hidden sculptures but by now much of the inter-generational carving skills had been lost. “Today, it is only the older men of the district who have retained the sculptural skills and occasionally carve figurines.” Master carver Antonio Soares, a custodian of this ancient skill, first met the curator in 2002. You get some understanding of the cultural context from Barkkman’s account of their first meeting. “Antonio sat patiently outside the cafe entrance … As the cafe drinkers left the cafe one by one he would pull himself up, together with his hands full of sculptures … and launch into his sales pitch.” Now sold as tourist souvenirs in Dili, these elegant, sibylline sculptures provide significant economic rewards to the carvers of Ataúro Island.

Similar repercussions were felt in Australia. In 1877 the Lutherans established a mission at Hermannsburg in the Northern Territory. The government lease covered 4,000 square kilometres and was home to the Arrernte, Luritja, Pitjantjatjara and the Warlpiri. As with many of the early missions it was economic necessity that they employed the skills of the traditional owners to produce handicrafts for employment and income. Albert Namatjira, a traditional Arrernte man, was one such artist who began producing plaques and boomerangs for sale.

Some Indigenous Australians have also embraced Christianity and adopted iconography into their artwork. In 2004 the Flinders University City Gallery in Adelaide hosted a landmark exhibition titled Holy Holy Holy. The exhibition documented the interaction between Christianity and Aboriginal culture. In an essay from the accompanying catalogue Marcia Langton expands on this accommodation of Christian values. “For art historians and some visual anthropologists, it is self-evident that many works of art which purport to be, or are asserted to be, ‘Aboriginal art’, are artefacts of the colonial encounter. While all human societies have artistic traditions that provide a window on the ideas generated by culture, when artistic traditions become engaged across cultural borders, the results can be complex social phenomena, not easily perceived or understood, especially in the colonial and postcolonial worlds.”[3]

Christian missions were designed to systematically annihilate the spiritual traditions of Indigenous culture but culture is adaptable and resilient. Despite centuries of upheaval, oppression and transition the unique skill of Ataúroan carving endures. Joanna Barrkman concurs, “the shifts and changes in the creation of Ataúro sculptures over time may be considered by some as representing a loss of tradition, reducing the artform to a remnant of its origins. Yet these transformations have endured a process through which sculptural skills have been re-cast and re-applied in the face of major social changes and influences”.

The sculptures in the exhibition are undeniably beautiful but they represent an irrevocable change in life circumstances. The renditions of traditional animist beliefs have been whittled away by the tools of Christian coercion and conversion. Even if the figures still portray important icons, the purpose of the sculpture has clearly evolved from religious pursuit to economic survival, linked to new audiences for art. As East Timorese leader Jose Ramos-Horta stated in 2001 “Thankfully, a small number of memories were immortalised by our ancestors in wood, stone and metal ... But even these ‘concrete’ memories are grievously imperilled. In recent years they have dwindled in number as they have literally been cut down by the forces of neglect, war and social progress.”[4]

Footnotes

- ^ David Palazón, Ro'o Putin Hatin – The Boat from Putin's Place, 2015, SETAC & Victor de Sousa Timor-Leste

- ^ Joanna Barrkman, The Sculptures of Atauro Island, 2017, Charles Darwin University, Office of Media, Advancement and Community Engagement.

- ^ V. Thwaites, W.H. Edwards (eds), Holy holy holy: 13 Contemporary Artists Explore The Interaction Between Christianity and Aboriginal Culture / Ian W. Abdulla ... [et al.], Flinders University Art Museum, 2004, Adelaide.

- ^ José Ramos-Horta as President for the Democratic Republic of Timor Leste from the foreword of Mark Gordon,‘Ancient Echoes’, The Mark Gordon Collection of Southeast Asian Art, Talisman Publishing, Singapore, 2011.