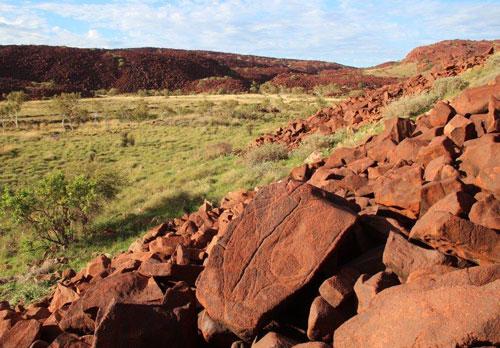

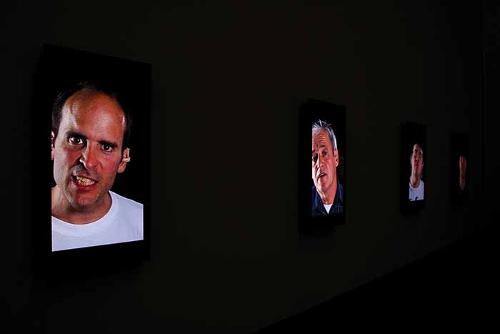

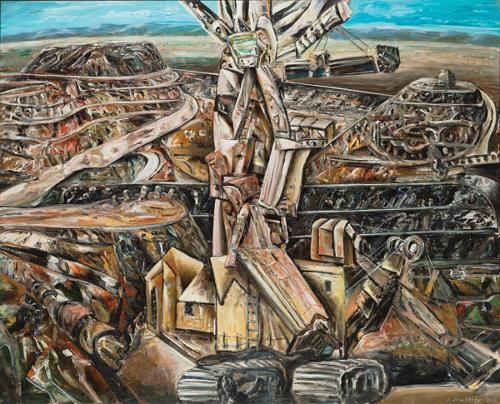

Reverse engineering: The mining photographs of Simryn Gill

You may not be enthusiastic about stromatolites and the cyanobacteria, but given that they paid for the nation's Nissan Patrols and Miele electric ovens, television sets and holidays in Provence, Australians might at the very least spare them a thought in their prayers.