Although it is supposedly death that gives rise to the possibility of life in another, the donor heart is always alive at a cellular level... as the recent breakthrough of the so-called beating heart transplant… shows[1]

It is a developmental achievement to come to have a body in the sense that Winnicott[2] intends when he speaks of the dawning awareness of the lived specificity of one's body. Virtuoso aerialists and dancers notwithstanding, that bodily awareness arrives late (if ever) for many of us and frequently requires prosthetic techniques like mindfulness and yoga to bring it to fruition. Having glimpsed such awareness, it may then seem self-evident that our bodily reach is defined by the limits of our nerve endings, blood circulation, span of breath and skin. My sense of bodily boundaries has become vastly more distributed across an array of media from the biological to the uncannily cultural after an encounter with installation artists Peta Clancy and Helen Pynor, reading about organ transplantation in scientific, philosophical and phenomenological literature, and being offered the accounts of donors, recipients and expert surgeons. I realise that, (as Helen and Peta entitle their project) The Body is a Big Place.

Transplanting parts of one person’s body into the body of another saves the life of that other and transforms the lives of those touched by the experience. It is a 'gift of life’, likened by some to Marcel Mauss’[3] notion of ‘gift exchange’, of exchanging goods without money.[4] From living donor accounts it emerges as a gift given without obligation (or regret)[5] and with no reciprocation sought, and none seen as possible by recipients.[6] The delight taken by living donors in the newfound joie de vivre of the recipients is perhaps reciprocation; as Peter,[7] a living donor of bone marrow, notes of the recipient: "she is now in total remission…doing things she has never done in her life before…into hiking, mountain-bike riding and other adrenaline sports". Far from expecting reciprocation, in living donors in Southern England there was a sense that the gift should not be spoken about too much so that the recipient can “move on with their lives” without feeling excessively beholden.[8] For young (liver) recipients, after the challenge of a life-threatening illness while achieving normal developmental milestones, what was urgently sought was a return to normalcy.[9] There is some reciprocation perhaps in the anonymous letters of thanks from recipients to donor families. The purview of the body is expanded as these families become part of the exchange when they endorse, after the death of their family member, the wishes that person had expressed in life to enhance the lives of others by donating parts of their body.

It is not a simple exchange - like a rose or a ring passing, in touch, from one hand to another. It traverses many boundaries that are at once physical, conceptual and uncanny. The DNA of the organ remains a stranger to the new body[10] and lifelong medication is required, with all the attendant risks and challenges of that. It is not a simple person-to-person exchange, there are many gatekeepers safeguarding the process – testing compatibility, seeking informed consent, protecting anonymity. The exchange has become richer and more complex as science has pushed the boundaries of the possible with beating heart transplants.[11]

Yet, implications flow beyond medical concerns of blood, tissue and separable body parts. Conceptual boundaries fluidly re-amass as medicine redefined death in 1968 as centring on brain rather than heart. The emotional and practical outcome of this is shaped by beliefs held by donor families about the meaning of death and life.[12] While affected families readily grasp the concept of their loved one being dead by virtue of brain stem disconnection from the rest of the body, this translates complexly into lived experience and decision-making. For donor families this experience frequently exceeds language, finding its way into compelling gesture: “Mr Andrews…made a cutting action at the back of the neck demonstrating severance of the spinal cord and thus ‘there was nothing else I needed to know.[13]’” Yet for some, Gillian Haddow found, there can be a lingering sense of personal vestiges being attached to the organ which comes to animate another body, a belief that seems to arise where there is an identification of self and embodiment. This intriguingly acts both as an incentive to endorsing organ donation – seen as promoting a kind of living on, and as a disincentive – where an intactness of the lost loved one’s self is seen as linked to bodily intactness. There is what Mauss called “the spirit of the gift” illustrated by a comment from Mr Evans: “parts of him that were very much alive are still alive. I think eh, I felt that that was em, a strong consoling moment for me”.[14]

Organ transplantation is an ‘uncanny’ transmission in the original sense intended by Freud[15], whereby what was once the deepest interiority of one person comes to light, when it is briefly sustained in external media and is then re-embodied once more within another person. This echoes fascinations that are mutually compelling for Peta and Helen, the skin as a permeable membrane between outside and in, the nature of biological memory. It is an exchange that occurs in a richly social medium including those who support and love the donors and recipients[16]. It is also an intensely cultural exchange where the tacit norms surrounding what can be spoken within a given culture or subculture is put to the test. And there are technological media implicated in the exchange as well – prosthetic machines which keep intact cellular life, which keep the beat going, until a new embodied home is found for the heart.

Focussing on organ transplantation reveals just how distributed our bodies can be and are; distributed through the networks of sustaining support, reliant on and incorporating scientific and medical expertise and cutting edge technological media. The bodies that participate in transplanting life implicate themselves in belief systems about the nature of personal continuance, in philosophical concerns of embodiment and selfhood in regards to biological memory and vestiges of personal continuance, in excavations of the cultural imaginary[17] informed as much by which anxieties we would like to skip over or fail to entertain too deeply, as by the joyous and boundless capacity for identification which can result in the sense of personal vestiges being attached to the beating heart that comes to beat in another body. Transplanting life opens us to experiences that stretch the limits of language with previously unthought possibilities, and can provoke a dumbfounding into wordless depths of feeling.[18]

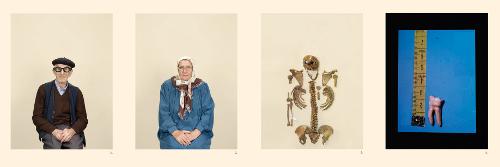

It struck me that speech is rendered impossible in the videos which form part of the art installation by Helen and Peta. Donors, recipients, family members of the transplant community, are united in the watery medium of a pool, though temporally disparate as each rises to the surface for breath and falls back into a mobile, yet peaceful group, bodily present to each other and silent. I found myself a silent witness. It is the art which has a voice, and which gives a voice to issues which are challenging to confront; our finitude, the intactness of bodies, the uneven aging of parts of our bodies due to heredity, lifestyle or chance, our reliance on the kindness of strangers at times when life is in the balance. Peta and Helen draw us into the pool of life.

The Body is a Big Place is a multi-layered project each artist felt could not have occurred without the other with their different and overlapping hybrid forms of expertise. Each felt emboldened, accorded courage by the other as they wish to lead us to deepen our relation to our own interiority. Their process in acquiring an organ to set up a pair of beating hearts of pigs was something of a parallel process to the likely experiences of true organ recipients; concerns about timings, accidents, phone calls and contingencies, tracking down scientists with the requisite knowledge, and being prepared to go back to the drawing board if it all falls through.

A representative of dedicated medical expertise, Gregory Snell[19] suggests “The individual organ donor stories are a combination of fate, bravery and legacy. The individual organ transplant recipient stories are a combination of luck, hard work and hope.” For those of us who have had our lives transformed by meeting people we may not have come to know but for these remarkable processes[20], uncovering the complexities of a process we may have managed not to think about too deeply also requires a tenacious courage. Transplanting life arises as a byproduct of the often untimely death of another. The interwovenness of life and death can sink as cliché or rise as an awareness that makes us vitally glad to be able to draw easy breath.

The Body is a Big Place

Peta Clancy and Helen Pynor

The Body is a Big Place was a new media commission staged at Performance Space, Sydney from 3-26 November 2011, realised collaboratively by Helen Pynor and Peta Clancy with sound by Gail Priest and curation by Bec Dean.

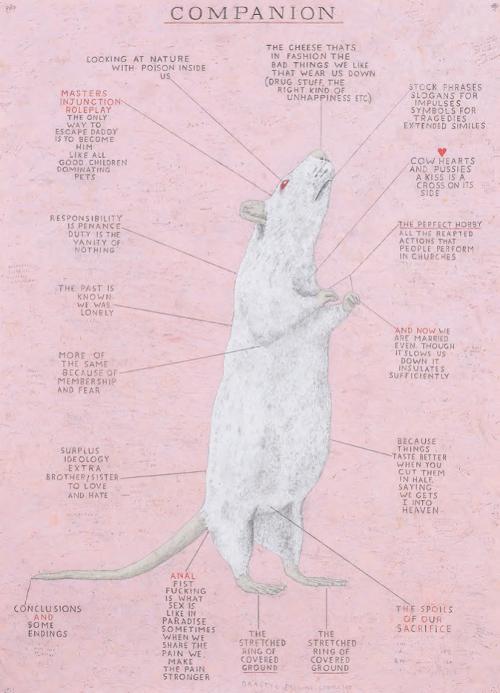

The work explored the fluidity between bodily boundaries inherent to the organ transplantation process, the ambiguous boundary between life and death, and the complex responses reported by organ transplant recipients. The Body is a Big Place incorporated live (biological) art, a 5-channel video projection and soundscape. Performers in the video work were all individuals who have had experiences of organ transplantation.

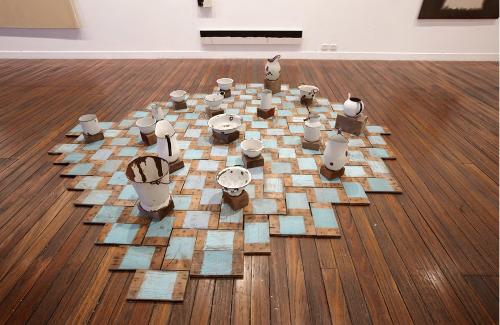

Shown with the video was a heart perfusion system. Twice during the exhibition viewers were invited to witness the reanimation of fresh pig hearts, obtained from an abattoir, attached to the perfusion system which supplied essential nutrients at body temperature. Reanimation of the hearts was reliant on physiological processes inherent to the hearts themselves, not on a mechanical support. Professor John Headrick and Dr Jason Peart, Heart Foundation Research Centre, Griffith University, Queensland, were the collaborating scientists for the heart perfusion system.

Footnotes

- ^ M. Shildrick ‘Contesting Normative embodiment: Some reflections of the psycho-social significance of heart transplant surgery’ Perspectives:International Postgraduate Journal of Philosophy 1, 2008, pp12-22

- ^ D.W. Winnicott ‘Primitive emotional development’ in D.W. Winnicott (ed) 1988 pp99-160 London, Free Association Books. (Original work published 1945.)

- ^ M. Mauss The Gift: The Form and reason for exchange in archaic societies Routledge, London 1990

- ^ R.C. Fox, & J.P. Swazey ‘The courage to fail: A social view of organ transplants and dialysis’ Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick, new ed 2002; P. Gill & L. Lowes ‘Gift Exchange and organ donation: Donor and recipient experiences of live related kidney transplantation’ International Journal of Nursing Studies 45, 2008, pp1607-1617

- ^ A. Lennerling, A. Forsberg, G. Nyberg, ‘Becoming a living kidney donor’ Transplantation Vol. 76(8) 2003, pp1243-1247

- ^ Gill & Lowes ibid, 2008

- ^ Peter Miller, a donor participating in video in The Body is a Big Place who shared his writing capturing his personal experiences of bone marrow donation

- ^ Gill & Lowes, ibid. p1613

- ^ Wise, B.V. ( 2002). In their Own Words: The Lived Experience of Pediatric Liver Transplantation, Qual Health Res, vol. 12(1) pp74-90

- ^ Shildrick, M. (2008). p19 ibid

- ^ Randerson, J. (2006) Britain’s first beating heart transplant heralds new era. The Guardian, 5. May 2006

- ^ Haddow, G. (2005). The phenomenology of death, embodiment and organ transplantation. Sociology of Health and Illness, Vol. 27 (1) pp92-113

- ^ Haddow, G. (2005). Ibid p100

- ^ Haddow, G. (2005). Ibid, p106

- ^ Something that normally remains ‘secret and hidden but has come to light’. Freud, S. (1919) The ‘Uncanny’. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XVII (1917-1919) Hogarth Press: London

- ^ Spouses were adamant that health care personnel should recognize them as co participants in the critical life event of cardiac transplantation, McCurry, A.H. & Thomas, S.P. (2002) Spouses’ Experiences in Heart Transplantation, West J Nurs Res March vol. 24 no. 2 180-194

- ^ “the deployment of, and unacknowledged reliance on, culturally intelligible fantasies and mythologies within the terms of what claims to be a system of logic” (2000, p137) cited in Shildrick, (2008) ibid, p13

- ^ Peter Miller, ibid noted of his conversation with his mother when they heard that the recipient’s health was improving; ‘we hardly said a word – we both eventually said we will talk another day when we stopped crying’

- ^ Personal communication of experience by Prof Gregory Snell, MBBS FRACP MD AO, Medical Head, Lung Transplant Service, Alfred Hospital and Monash University, Melbourne

- ^ I would like to dedicate this writing to the memory of sparkling Dr David Cairns formerly of the Department of Psychology, Macquarie University and to the ongoing courage of his wife Sue