In theming ISEA 2011 "Uncontainable", Artistic Director Lanfranco Aceti points to the sprawling, mobile, post-networked state of contemporary “new media”. True enough - but the title also riffs on the Istanbul Biennale's “Untitled”; and with ISEA timed to coincide with the Biennale, the relationship between the media arts scene and the mainstream contemporary art world became a core theme of the conference content and the ISEA experience. As a long-running academic and artistic symposium, ISEA has helped form the media art scene’s sense of itself – staking its claims for legitimacy and significance. Yet a recurring theme at ISEA was frustration that the art world (handily embodied in the Biennale) remains hostile to anything more technically sophisticated than a DVD player. But are labels like “new media” part of the problem, or part of the solution?

The conference program itself certainly lived up to its name, with a sprawling plethora of discussions, exhibitions, performances and academic papers. The daily keynotes formed a useful anchor to all this. At their best they captured something of the zeitgeist – as in Walter Oricchio’s presentation, which posited a new “algorithmic” cultural order, where artefacts are no longer authored by humans, but by computational processes. Oricchio neglected the potential for human - even artistic - intervention and agency here; Sara Diamond by contrast, mapped out a transdisciplinary model for data visualisation in which artists and designers play a crucial role. Art itself came under fire in Jay Bolter’s portrayal of “Digital Plenitude and the End of Art”, which characterised a networked culture as one without a shared centre, where established cultural forms are simply overrun by a million different communities of interest. Media art practice might be plugged into that same network, but as Bolter implied this doesn’t make it special: it too must fight (like Art) for a slice of actual cultural life.

The conference program bore out Bolter’s narrative of fragmentation, with a proliferation of themes and sub-scenes vying for attention. From bio-art to robotics, from hacktivism to augmented reailty and wearables in up to seven parallel streams. Among the most satisfying presentations were those that provided a glimpse of practices with connections beyond the art game – whether visualising shipwrecks or discussing the utopian social promise of peer-to-peer economics. These edges between art and non-art seem to be the most productive, for example George Legrady outlined a lab-based model of practice linking design, academic research and computer science. In cases like these – where interesting digital practice has established its own way of getting along in the world – the question of “art” is far less relevant. At the same time it was clear how deeply this media arts scene, and the economic logic of the conference, is entwined with the institutional demands of academia.

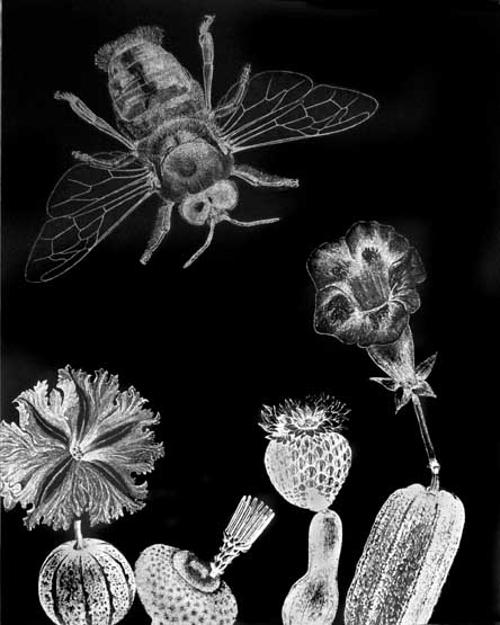

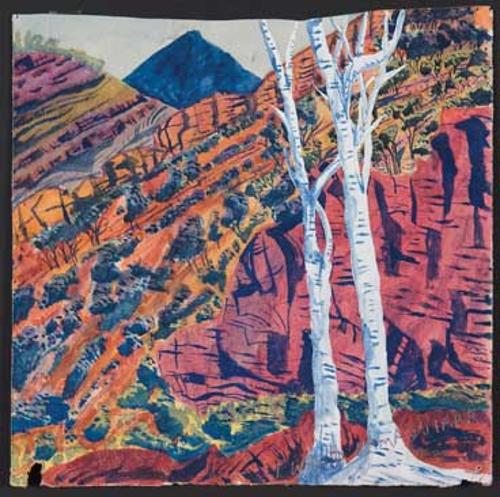

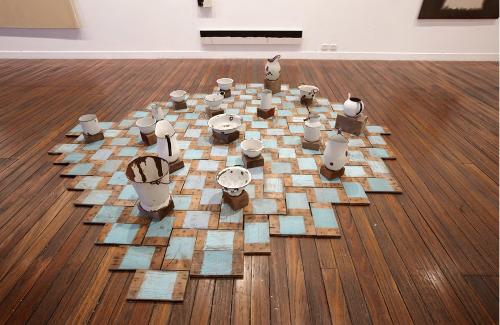

The ISEA exhibition program matched the conference program in scope and diversity, with numerous shows and sub-shows across half a dozen venues. Australia has always been well-represented in this scene, but here its presence was almost overwhelming, with three entire sub-shows of Australian work. The main Uncontainable exhibition occupied the Cumhuriyet gallery, a grid of beautiful vaulted rooms – perfect containers, in many ways, for the often awkward demands of a media art show. The show had moments of brilliance; a personal highlight was seeing Mari Velonaki’s girl-like robot Diamandini drifting through the gallery’s arched portals. As a whole however the show was sprawling and difficult to read. With no interpretive context provided the works that fared best were those with a self-explanatory directness, such as Patrick Tresset’s charming drawing robot Paul who produced loose, sketchy portraits of gallery visitors. The exhibition was also afflicted with 'technical issues’, with some works (such as Julian Oliver’s psworld) non-functional most of the time.

These issues of curation and production return to the question underlying ISEA – of art-world envy and self-marginalisation. Comparisons with the Biennale are inevitable, if a little unfair – ISEA is run on a shoestring; but if media art wants mainstream acclaim, it must above all deliver the goods. Interestingly another non-ISEA show made Istanbul’s best case for the vitality of the media arts. Matter Light 2, curated by Richard Castelli at the privately funded Borusan Music House, spanned sculpture, light art, animation and installation, both spectacular (as in Christian Partos’ kinetic light sculpture VISP) and conceptually acute. This exhibition shows that while media art may not work within traditional visual arts paradigms, other approaches are viable.

Twenty-one years after Sydney hosted the third ISEA, the symposium returns to Australia in 2013. Themed “Resistance is Futile”, and headed up by Marcus Westbury, the signs are promising for a festival that takes on the ubiquity of digital media both within and without the art world.