It seems very logical that the lurid, steamy paintings of Stewart MacFarlane should have been painted in Brisbane (as many of them were) but the fact that he began his career in Adelaide provides another telling element in the perverse mystery of his pictures.

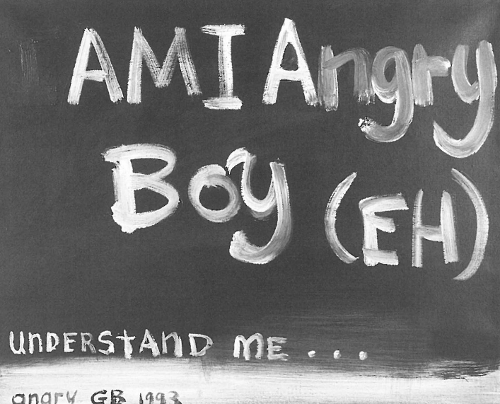

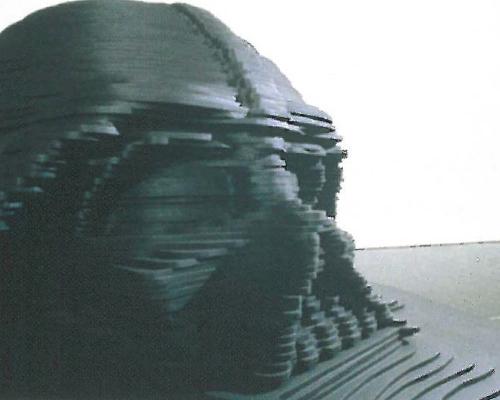

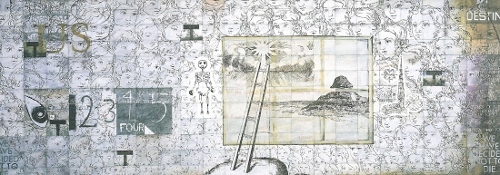

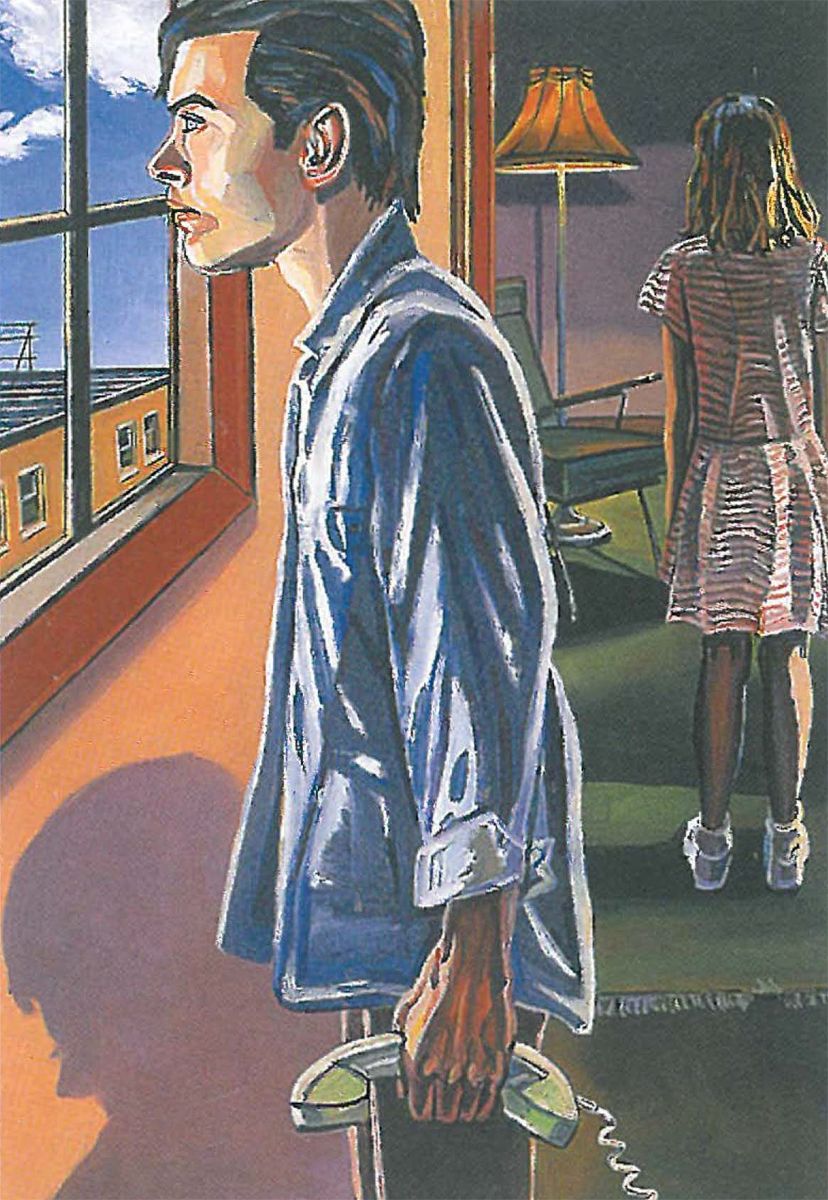

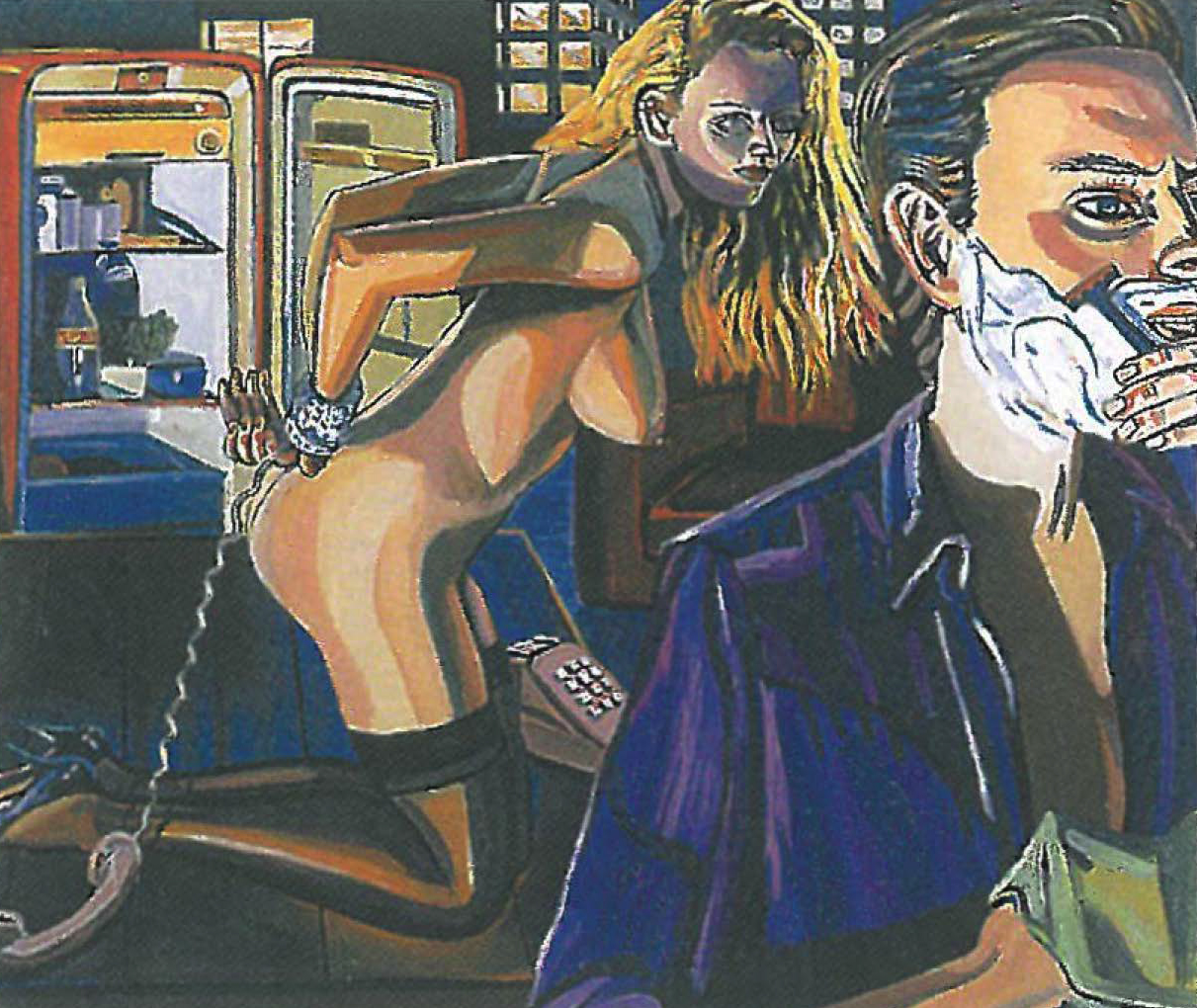

His exhibition Compulsion at the Brisbane City Gallery is a compilation of the artist's more sinister, sexual and latently violent works. Each one seems to be a still from a B-grade movie thriller involving a great deal of sex and very little political correctness. Couples in various states of undress inhabit cheap rooms, masturbate, smoke cigarettes, are tailed by the cops. The pictures illustrate a sleazy sub-tropical underworld where morality has been melted by the heat; MacFarlane ventures into it with as much thoroughness as the Fitzgerald Inquiry.

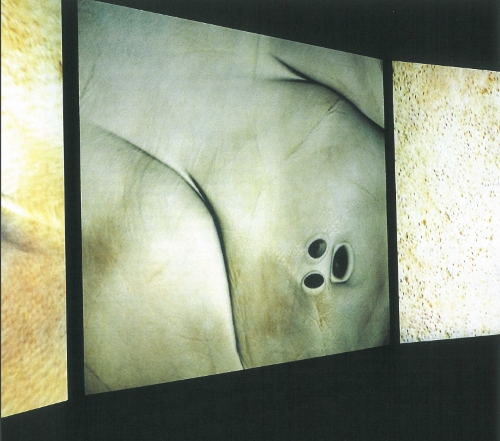

The viewer's initial impression on walking into the gallery, however, aside from noting the amount of exposed and often tumescent flesh, is an intense sensation of brilliant colour. It is the excessive colour of Mambo, Hawaiian shirts and pizza with the lot. This is heightened by the harsh, theatrical-looking lighting in which MacFarlane generally portrays his subjects. Despite the preponderance of night-time scenes, and the large amount of black he uses, the paintings are only dark in the metaphorical sense. While observing certain conventions of a Damon Runyon detective story, such as brusqueness, low rent settings and broads who get slapped around, MacFarlane's pictures are more like a carnival than a crime scene.

It is an exceptionally good exhibition, because of the quality of the works and also the astuteness of the selection by curator Simon Wright. The fevered atmosphere is unrelenting and the unsolved mystery conveyed by individual pictures creates a continuous random narrative around the gallery.

MacFarlane characteristically combines enigmatic narrative elements, and provokes the question of what exactly is going on in his pictures. Each one offers a conundrum for the viewer to solve, from clues such as a bottle of beer, a transvestite and a naked man on a bicycle. The puzzle is of course always unsolvable, often because it is simply too strange. This is where the artist's Adelaide origins seem to be significant. Although the paintings are in many cases extreme (and this group seems to have been assembled largely according to that criterion), in a politely South Australian way they are also understated. Adelaide's reputation as the bizarre crime capital of Australia may be a myth, but the city's sense of restraint, expressed in its modest scale and the well-bred decorum, is more directly palpable.

MacFarlane has lived in many cities and his pictures are emphatically urban. The lives lived by the characters in his narratives are colourful to say the least, but they nevertheless convey the sort of urban desolation and feelings of emptiness that have become the essence of particular genres of cinema, literature and painting. The mood he creates is like an R-rated version of the art of Edward Hopper, the 20th-century American painter of quiet, unfulfilled city life.

Although virtually everyone who writes about MacFarlane (including the artist himself) makes the connection between his work and the cinema, in purely visual terms it seems closer to the stage. The atmosphere is strongly suggestive of grease paint and footlights. A mask of theatricality is created by the elaborate artifice of his paintings, and always seems to be hiding something.

MacFarlane's works may or may not be intended to shock (comments in the visitors book outside the gallery in Brisbane City Hall suggest that many concerned citizens and ratepayers think that they are). Certainly the bounds of good taste are exceeded in all sorts of ways, from the garish colour schemes to the startling depictions of naked hermaphrodites. Exhibition visitors with delicate sensibilities may feel that MacFarlane has exposed them to too much information, but it is the information that he withholds that makes the pictures memorable.

Paradox is built into almost every aspect of MacFarlane's work. Although his brushstrokes are inclined to be crude slashes, the composition is precise. The wildly clashing colour is skilfully controlled and calculated for maximum impact. He frequently paints women as more pneumatic versions of Barbie, but always in a context where they provoke interest and speculation (especially when, on closer inspection, they turn out not to be women at all).

Compulsion identifies the most distinctive aspects of MacFarlane's work and turns them up to full volume. It is not a conventional survey exhibition, although it spans a quarter of a century. What may at first seem like a cacophony turns out to be a finely sustained and carefully modulated theme.