.jpg)

It is perhaps no accident that at the time Therese Ritchie’s exhibition Burning Hearts opened in Darwin the annual summer hysteria about juvenile crime in Alice Springs was heating up. There are calls for a youth curfew. Again, the local Murdoch paper announces: “We’ve had enough” with headlines touting “We don’t feel safe in our town”.

At the same time, without a blush, it is reported that the homelessness rate in Alice Springs is seventeen times the national average. The barely hidden message is directed at Aboriginal people living in central Australia, and it is not pretty. It is, for that reason, nearly a decade ago that Ritchie spent time in Alice documenting the reality of day-to-day life, the “ebbing and flowing” of tension in the town.

Her task was to paint, as it were, a different picture but above all to chronicle the harsh reality of life in the Northern Territory, which has been home to her for just under 40 years. Ritchie started in the Territory as an art student interested in painting, but quickly deserted that corner to take up photography, working with Martin Munz at what was then the Darwin Community College. Beyond that, her early work was shaped in three ways.

The first was being asked in 1988 to teach photography to young people at Borroloola, and document the historic return to country, on foot, through Yanyuwa lands that had been cut off from their traditional owners by the pastoral industry for 70 years. It was a transformative experience—both in terms of being exposed to Aboriginal people and culture in a profound way, but also in realising that she had been lied to. “I had been hoodwinked about my country’s history”.

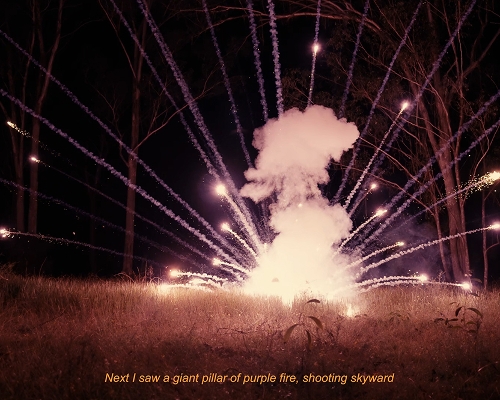

The second was working with other young artists at the Werehaus Artist Coop where she worked as a photographer, and was also exposed to blood, sweat and tears of collective workspaces and practices. It was a time in which she also documented political actions over Pine Gap and the anti-uranium movement.

The third was in the 1990s working at Green Ant Research Arts and Publishing where she worked as a photographer—including as a freelance photojournalist for the southern Fairfax and Murdoch newspapers. It was during this time she learned the arcane world of offset printing and typography, layout and design—including the early days of the transition to digital applications that was rapidly transforming these crafts. Programs such as Photoshop and Painter have allowed her to explore collage and forms of manipulation seen in so much of her later work.

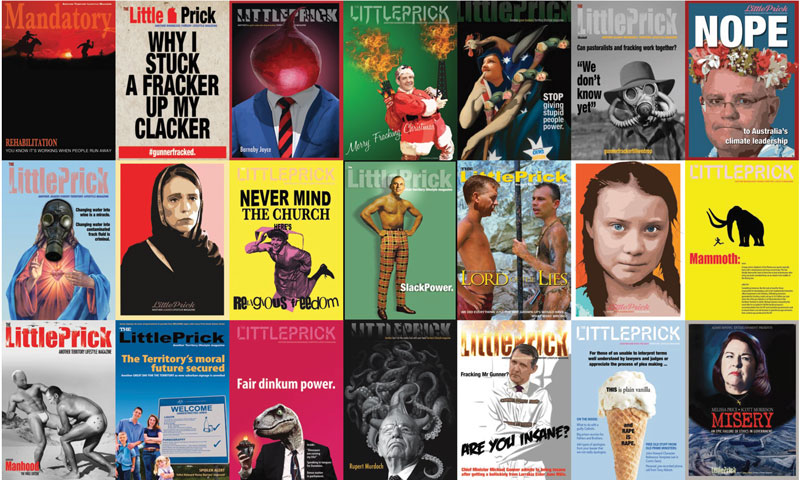

Only one work of that period—the savage mauling of Pauline Hanson in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?—is exhibited in Burning Hearts, but is an important early work. The humour in her depiction of the regrettable racist redhead has often marked her artistic output. It is evident in many works, but perhaps summed up best by a large display of more than 40 of her LittlePrick magazine front covers. They are clearly the covers of a completely imaginary magazine, but uncomfortably close to the truth of what is going on in the bleakness of so much of today’s political landscape. She has put them out, often in near real time, much as a real magazine might—or should. Occasionally exhibited with other artists, LittlePricks have become a release of her rage and analysis—using stark humour in her political statements, also as a form of homage in featuring images of the leadership of Jacinda Ahern and Greta Thunberg.

This humour is also evident in her deliberate—often wild and wonderful—painted trompe l’oeuil collages, and her mastery of classical academic painting that stems from the High Renaissance, and notably applied to the masterworks of Australian and American colonial art. Here she has added in contemporary commentary, ranging from references to FIFO workers employed in the extractive industries, the follies of Territory politicians and the health challenges that disproportionally impact Aboriginal communities, with a prevalence of diabetes and other conditions, and the ongoing challenge of requirements for dialysis and organ transplants, as she draws attention to in Our Organs are Sacred (2011).

Another key work, Criminal Stupidity (2019), was for a short while threatened with banning from the exhibition, but wiser heads—and astute legal opinion from senior counsel—prevailed. It is a centrepiece of her exhibition, depicting the entire Northern Territory Cabinet hurtling into an abyss as a full-frontal condemnation of fracking.

.jpg)

But the siren song of this exhibition are the series of photographs—mostly in black and white—of her friends. Taken with an extremely small aperture, they sharply focus on larger than life portraits. These are what she laughingly calls, “the curator’s ‘Gay Wall”, as portraits involve a sample members of the Territory’s LGTBQIA community that have formed two exhibitions in recent years. They are quite deliberately not “coming out” photographs, but a response to the various tribulations, demonstrations of pride and mechanisms of survival in response to the homophobic world, with words that appear more than skin-deep painted onto the bodies of her trusting, defiant and much-loved subjects.

Here is truth to beauty, not just power, and a deep respect for her sisterhood and brotherhood. Nowhere is this truth to power, and Australia’s fraught history of colonisation and corporate invasion, more apparent than in Ritchie’s series of black and white portraits for Open Cut chronicling the historical legacy of genocide—and continuing history of takeover as invasion, in the fraught undertakings of the mining industry in the Borroloola region on the Gulf of Carpentaria. They are brutal images not only in what they describe, but also in response to the vapid and disingenuous marketing of government and industry groups alike. As messages of defiance, they feature statements inscribed in white ochre upon the bodies of First Nations peoples, to communicate power and pride, some of them in the language of the Garrwa, Gudanji, Marra and Yanyuwa peoples she has worked with for over 30 years.

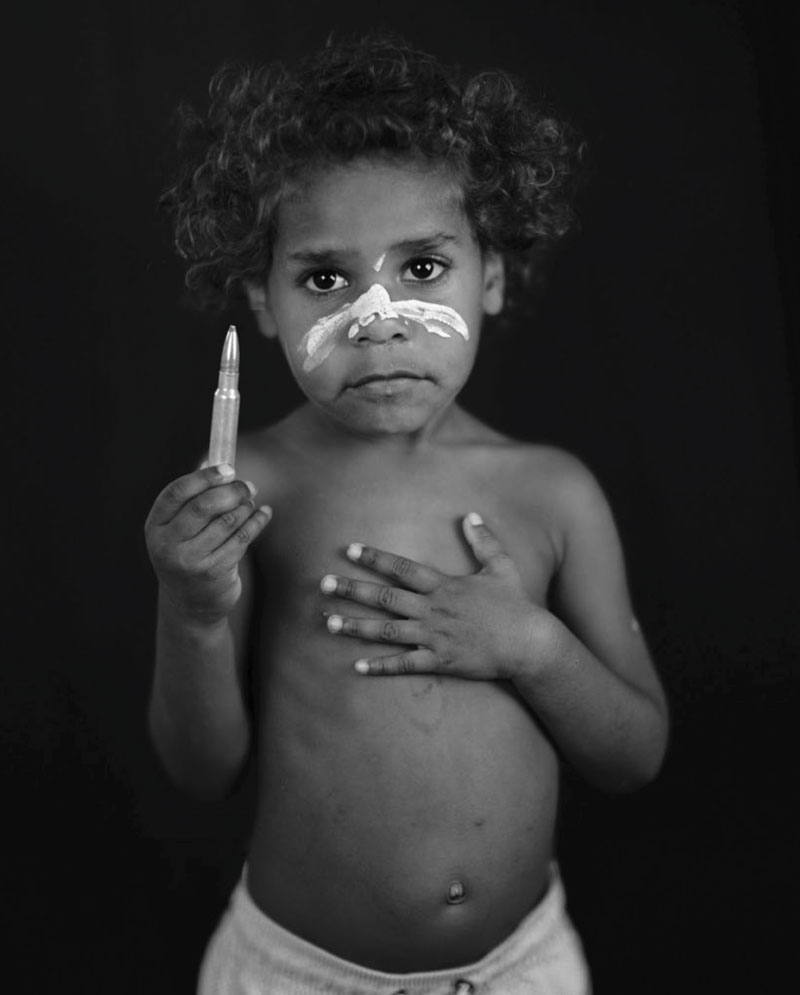

More confronting still are Ritchie’s photographs from Lead in My Grandmother’s Body, a series of images seen here for the first time. They depict a series of portraits of traditional owners of the region, from young children to adults, solemnly addressing the viewer. Each of them bear in the hand, a single 388-calibre rifle bullet: a vicious and enduring symbol of the 600 men, women and children slaughtered during the “wild time” of massacres from 1870 to 1910. But they also represent the current depredations of mining, and the lead slowly leaching into the environment—into the drinking water, and the blood and flesh of fish, animals and humans alike. It is estimated that this metallic plague will last another 1,000 years. As Garrwa elder Nancy McDinny put it to Ritchie: “It’s not the first time they put lead in our bodies. They put lead in my grandmother’s body when they shot our families.”

And therein lies the complication in Ritchie’s work—and continues far beyond the Borroloola photographs. Their power also lies in their arresting beauty and their commitment to uncomfortable truths in the confrontation with our history. The gestural symbolism, also drawing on the representations of a suffering yet glorious humanity—in European terms, akin to the portraits of the Christian Apostles and the Saints, and the blessed Christ Child. Hers is also a more home-grown variant of the cosmology of black and white photography championed by Robert Maplethorpe, with her portrayal of individual sitters and representatives from the community in larger scenes as tableaux vivants addressing multiple historical reflections around race, place and culture for the public record.

At the heart of Therese Ritchie’s extensive oeuvre represented here—the burning heart if you will—is a refusal to compromise as an artist. Her work is deliberately historically derivative in style, but clearly empowering to a community, and brandishes its politics for the benefit of developing a greater awareness of the lives of individuals enlarged upon through Ritchie’s journalistic agency and love of storytelling. As distinguished Aboriginal journalist, Lorena Allam, said in opening the exhibition:

Therese Ritchie is a truth teller. She tells the truth about this country and its history. Her work reflects the collision points of denial in our society, points that are everywhere you look. There’s the denial of massacres of our mobs all across this country but especially here in the NT, where they were going on right up until the 1930s.

There were at least nine massacres of Aboriginal people in the Gulf country where Therese works closely with Aboriginal people from Borroloola. That massacre history is long denied, but slowly it is being put together—using the records of the perpetrators, not just the survivors.

Aboriginal people talk about this, it is a huge part of our history, and she has worked to help us tell those truths. Being a truth-teller is not an easy path, but those of you who know Therese, know that she isn’t interested in another road. She couldn't create and she could not live with herself if she wasn't honest in her creative work and in her life.

This exhibition, beautifully curated by Wendy Garden, follows on from the previous year’s showing of work by Franck Gohier, as an important extension of the MAGNT’s curatorial practice of looking at the work of non-Aboriginal artists that live and work in the Northern Territory to complement the work of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities in the presentation of truthful, culturally rich and often defiant work that reflects on where we live.

.jpg)