‘Eco’ is a promiscuous prefix, mined from ecology, a word conceived in 1873 (from science) to explain the relationship between living things and their environments. It’s no accident that a growing awareness of ecology parallels the progressing burn of the industrialising world, and the escalated environmental degradation that continues. As environmental lawyer and art historian Tim Bonyhady argued in The Colonial Earth (2000), by the nineteenth-century, romantic artists were developing an environmental aesthetic—with the ardour of conservationists.

The term ecosystem came into use in 1935 (from botany) to explain the interrelatedness of all branches of science, but it was not until the exhibition Ecologic Art in New York in 1969 that art coupled with ecology, spawning ecological art (and later, ecoart) as a distinct category by the early 1970s. Ecofeminism was born in 1974, and ecocriticism was devised in 1978 by literary critic William Rueckert who hoped ‘that old pair of antagonists, science and poetry, can be persuaded to lie down together and be generative after all.’[1]

Contemporary art is abundant with its neologisms and faux‑verbiage, and while the eco-critical compound has limited use, the high response to Artlink’s public callout for Eco‑Critical suggests that doesn’t matter. Taken literally, ecology + critical (urgent, interrogative, acute) is readily interpreted—perhaps for all the wrong reasons, as Scott Robinson argues. In his mordant essay, no clod is unturned, from greenwashing curatorial agendas and bespoke art publications to the plenteous caring and deep listening approaches fostered by many contemporary artists. While some scepticism is critical, and (borrowing from Robinson) we don’t need artists to show us what the ecological scientists are telling us, there’s a strong call to nature and its nurture among artists in the age of the Anthropocene.

Whatever its terms and liaisons, we continue to make art, in, on, of, from and arguably for ‘nature’ and its living relations. And we continue to write about it. What emerges in both forms are several sub-genres shaped by the spectre of the climate crisis: ethically, politically, practically and existentially. Some artists (and writers) lean to the nihilistic, but there are many counterpoints. A recurrent theme is that solutions to some effects of climate change and related losses lie in the adoption of Indigenous knowledge systems.

Ecoanxiety is a common frame for examining the ecocritical moment, and Kathleen Linn’s analysis of recent works by Emily Parsons-Lord and Jacobus Capone suggests our complicity and yearning for another story. Michael Gentle’s immersion in exhibitions of Yindjibarndi artist Katie West’s ‘anti-metaphorical’ practice, and John A Hayward’s survey of the ecological origins of the Heysen Sculpture Biennial might appear to be very different examples of ecoart, but there are parallels between these relational artistic projects made in consultation and connection with their environments. South Australian duo Wills Projects similarly demonstrate a light touch in their creative partnership surveyed by Tegan Hale, as do local communities across Indonesia active in last summer’s hottest Jogja Biennale, reviewed by Bianca Winataputri.

Nipaluna / Hobart based academic Eliza Burke examines two separate projects by Tasmanian artists Julie Gough and Lucienne Rickard which share the common ground of species extinction witnessed through durational works of loss—occurring in plain sight, historically and right now. In Rickard’s four-year performance at TMAG, drawing and then erasing Australia’s long list of threatened species is a pretty direct metaphor for the human animal’s impact on other animals, which as Gough shows is a well-entrenched colonial practice.

In Darwin, the threatened Gouldian finch has become the focal point for a people’s grassroots campaign followed by Maurice O’Riordan. Defence housing developments on the city’s northern edge are bringing destruction to the finch’s habitat, while due north in the Timor Sea, Santos are forging ahead with the Barossa Gas Project despite opposition from Tiwi landowners and climate advocates. In response, Johnita has documented the Yangamini collective’s anarchic dissent in the form of methane-blocking butt plugs. Commissioned for the 24th Biennale of Sydney, it’s a topical arse-roots protest against global corporate and government extractive business models—both environmental and cultural.

Extraction as a metonym might be approaching peak use in contemporary art and its writing, but not without reason. Lu Forsberg’s private reflection on rare earth elements (REEs) extracted worldwide for use in all the technologies we all use all the time demonstrates another ubiquitous, universal dependency fuelling the anthropogenic climate cataclysm, as well as figuring in renewable energies and ‘green/capitalist’ mitigation strategies. Despite a temptation to despair when considering our collective carbon appetites, Ella Mudie examines low-carbon infrastructure and exhibition design in some leading Australian museums, a movement that is growing.

The world’s largest coal exporting port at Muloobinba / Newcastle has been a backdrop to some of our century’s most visible climate activism, from Rising Tide to Extinction Rebellion taskforces. In a social gesture, Ellie Hannon’s visual essay narrates a 36-hour shift on the Art-Raft as part of the 2023 People’s Blockade of the harbour’s shipping lane. Recovery, wellbeing and collective making are also centred in Chloe Watfern’s perceptive response to a visit to the Northern Rivers as part of her work for the Black Dog Institute, eighteen months after devastating floods in the region.

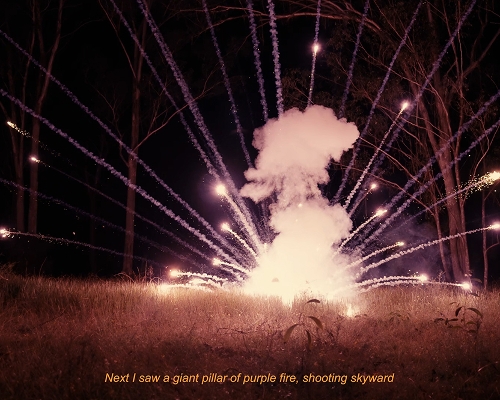

Recent collective memories of Australia’s 2019–20 wildfires were forged in the densely populated regions of Australia and memorialised by mainstream media in catastrophic firestorm imagery. By contrast, our cover detail from Chanamee, Never die (2023) shows a young desert oak / kurkara in a burn near Karrinyarra / Central Mt. Wedge, led by traditional custodians Nigel Andy and Terrance Abbott and filmed by Tim Georgeson. Launched in Polarity: Fire & Ice (reviewed for Artlink by Christina Chau), the work was commissioned by Fremantle Arts Centre and the Indigenous Desert Alliance, a collective of First Nations rangers and traditional owners formed in 2014. The IDA collaborate locally, including with the Australian Wildlife Conservancy, and internationally: they spoke at COP28 in Dubai last year, and continue to manage fragile desert ecosystems as they’ve always done. For their part, Fremantle have partnered with Carbon Positive Australia, where you can fund a tree for the future. Hopeless doesn’t mean ‘give up’. It means hope less, and act more, for change.

Footnotes

- ^ William Rueckert, “Into and out of the Void: Two Essays,” The Iowa Review 9:1, Winter (1978): 73.