.jpg)

During the peak of one of Perth’s hottest summers, Polarity: Fire & Ice at Fremantle Arts Centre (FAC) is yet another timely call for meditations on ecological change brought about by global warming. Showing as part of the 2024 Perth Festival and built entirely of photographic and video works, Nhanda and Nyoongar curator Glenn Iseger-Pilkington brings together Australian artists Cass Lynch and Mei Swan Lim and Tim Georgeson who collaborates with the Indigenous Desert Alliance. The northern hemisphere’s Adam Sébire and Maureen Gruben locate the aesthetics and symbolism of (melting) ice down-under. Collectively, all the works communicate stories of connection to Country in the age of climate change, and nowhere is immune to this crisis: vast tracts of the earth from Boorloo/Perth to Kalaallit Nunaat/Greenland above the Arctic Circle, Tuktoyaktuk in Canada’s Northwest Territories, and Australia’s central and western deserts and eastern seaboard.

Polarity: Fire & Ice highlights many environmental consequences of the colonial—both historical and ongoing—erasure, censorship and disregard of scientific and cultural knowledge held by Indigenous cultures and communities. Witnessing devastating bushfires, rising sea levels, reduced biodiversity on land and sea, the exhibition follows familiar territory in contemporary climate change art, positioning the local as a shared global experience from a constellation of locations to capture ecological precarity worldwide. Here artists highlight the urgency of acknowledging the essential role First Nations knowledge and custodianship has in understanding repairing and potentially limiting ecological crisis, and rebuilding lost connections to Country. Ultimately, this necessitates a cross-cultural approach, and FAC has a strong curatorial history of working with Indigenous artists, non-indigenous artists and Indigenous communities, a tradition this exhibition continues.

‘Polarity’ denotes extreme positions or characteristics, but it is also the quality of an object producing and containing opposing charges. Such a term signals contradictory elements, even in extreme measures. In this context, polarity stretches across the art centre spaces, reversing hemispherical polarities, with fire in the northern galleries and ice (permafrost, glaciers) in the southern space.

As an exercise in artistic expressions of truth telling, what provocations, critical ideas and actions might emerge? What might we learn from these poetic accounts, or from being confronted with such unsettling polarities? Can such projects truly promote deep listening? It maybe that the artists are working harder than the collective whole of the exhibition, which while spectacular, also falls into the clichés of many exhibitions deploring the Anthropocene.

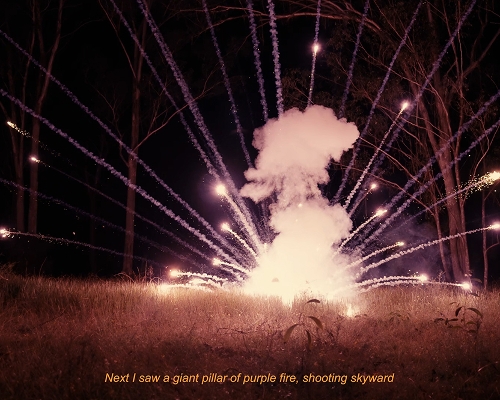

Some compelling examples are Georgeson’s photographic and video installations, which provide captivating fire scenes to remind viewers of the force and power of bushfires that pulse uncontrollably through the country each summer, but also offers alternatives. A collaboration with senior custodians and Luritja speakers Nigel Andy and Terrance Abbott at Karrinyarra, Chanamee, Never Die (2023) emphasises the now well‑known principles of controlled cool, mosaic or cultural burns: the land care practices that are essential (although widely debated) in avoiding destructive bushfires, now and into the future.

.jpg)

Paralleling Georgeson’s work with the Indigenous Desert Alliance fire ‘bosses’, albeit in the polar-opposite remote community of Uummannaq 600kms above the Arctic Circle, Sébire’s works concentrate on rapid adaptations that locals must undertake due to impacts of global warming. Through Sébire we witness changing tides, unstable ice coverage and warm winds, leading to altered seasonal practices of hunting, ice‑fishing and commuting. Georgeson, with Andy and Abbott, and Sébire bring first-hand intimate accounts of land care, and the co‑adaptation or ‘mitigation’ necessary for living with a changing land.

Placed at the fulcrum between the elements of fire and ice is the video Dampland (2024) by Boorloo/Perth artists Cass Lynch and Mei Swan Lim. Narrated by Lynch, Dampland shares stories and knowledge of Nyoongar Boodjar from the Darling Scarp, Swan Coastal Plain and Wadjemup/Rottnest Island, recalling the rising seas that came after the Last Ice Age (c 25–16 thousand years ago). Lynch and Lim emphasise Nyoongar Dreamtime as an intimate and cultivated expertise about living with Country during extended ecological flux—key knowledge for how communities might tread facing environmental precarity into the future.

In Stitching My Landscape (2017) Gruben offers a reparative performance by stitching red broadcloth across 300m of ice and snow in the arctic, north Canadian community of Tuktoyaktuk. The film shows Gruben digging ice fishing holes, anchoring the cloth into the snow and rolling it out to the next hole to form a zigzag pattern across the ground that evokes the trim often used in Inuvialuit wear. The zigzag stitch is commonly used in sewing for fabrics that stretch and shift; it is a technique that accommodates dynamic tensions. In this case, the work offers an aesthetic gesture towards flexibility and adaptation during environmental change. It is a response that privileges local practices responsive to global concerns, and offers a small but basic truth: if prevention is impossible, adaptation is inevitable.

Effective exercises in truth telling require viewers to listen well. Or, as Helena Grehan argues there is an ethics to ‘slow listening’,[1] which requires commitment from the viewer to ‘pause, to concentrate, to respond carefully and in doing so to take ‘respons-ability’ for the material, ideas and provocations that arise’.[2] In Polarity: Fire & Ice, viewers are literally required to sit low on bean bags and benches, and take time with the stories shared in video and photographic installations. Here slow listening requires taking witness, acknowledging individual and collective documentation, and inclination to absorb the works without ego, from which point individual and collective action may arise.

Another elemental work for the Perth Festival which requires acts of slow listening, although of a different kind, is Linda Tegg and Balladong Whadjuk woman Vivienne Hansen’s Wetland. Commissioned by Perth Festival curator Annika Kristensen in response to the theme Ngaangk (Nyoongar for sun or mother), Wetland brings audiences to the arcade basement (via escalator or lift) from Hay and Murray Street Malls to where remnants of a former 1990s food court remain. Around and between the dormant vendors is a wetland filled with edible and medicinal native plants endemic to Boorloo’s brackish wetlands, now covered by the Perth CBD. Meandering through the work Wetland presents a provocation to viewers in slow listening and take ‘respons-ability’ for ignored Nyoongar knowledge and expertise of the landscape’s care. Knowing that Wetland is a temporary occupation before the Carillon City arcade is redeveloped by Andrew Forrest’s property enterprise Fiveight, viewers grapple with competing conceptual layers of capitalist, geological, Indigenous, dream time, commercial, and ecological life cycles. Wetland reminds viewers of the land and water which has been exploited by colonial commerce, including waterways and aquifers that continue to flow under ground level. Such acts of slow listening have been long disregarded, and will continue to be after Wetland’s brief occupation. It may also be a harbinger of a future in which rising sea levels have the last word.