Monographs on Australian craft practitioners are still rare, although publications have accelerated in recent years. In South Australia the annual SALA monograph has featured two craft practitioners over a ten-year period – with glass artist Nick Mount in 2002 and a monograph on Julie Blyfield just published in August. The annual Living Treasures: Master of Australian Craft monographs published by Object in Sydney have profiled ceramist Les Blakebrough, glass artist Klaus Moje and jeweller Marian Hosking, with the next three just announced being Liz Williamson, Kevin Perkins and Robert Baines. Such publications are unlikely to be viable from sales alone, so it is not surprising that commercial publishers have been reluctant to take the risk without subsidy from State governments and the Australia Council.

Just published in Perth with support from Arts WA is an incisive monograph on West Australian ceramist Pippin Drysdale by Ted Snell. It sets a benchmark amongst recent publications of this kind. As one would expect, production values are high. The text is well spaced and legible and superb images of Drysdale's ceramics are interspersed throughout. These are usually in the right places for reference, in comparison to the SALA series where the images are in a separate section and a lot of flipping back and forward is needed. Primarily though, it is the calibre of the research and writing by Ted Snell that lifts this monograph. Here we have a writer who is the equal of his subject - in terms of professional credentials, skill and insight. Snell has written a substantial book of five chapters, dividing Drysdale's artistic evolution into four eras. His research is thorough, delving first into her upbringing and then revealing her artistic development almost vessel by vessel from her beginnings in the 1980s, to her present status as a distinguished Australian ceramist of international standing. My sole reservation is that after the biographical emphasis on Drysdale's youthful experiences in the second chapter covering 1943-81 we learn virtually nothing of her personal life in recent decades in the following chapters. There is a shift from personal biography to artistic monograph that is too abrupt.

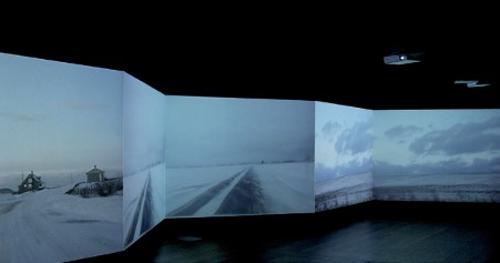

As the title Lines of Site implies, Pippin Drysdale's vessels are intimately connected to the West Australian landscape. Juxtaposition of vessels with the glorious aerial landscape photography of Richard Woldendorp reveals how closely her ceramics are grounded in the tonal and linear patterns of the land. Snell is at his best articulating this quality of poetic immanence and of resonance with the landscape. Through in-depth engagement with particular vessels or series he traces her increasing mastery of the allusive and abstract power of the ceramic medium. He has a rare eloquence amongst visual art writers, with the power to avoid both cliché and obfuscation, to find just the right word to illuminate both the art and the artist's intentions. Perhaps occasionally his passion for Drysdale's ceramics sends his descriptive powers into overdrive, verging perilously close to hyperbole, but this is a rare lapse.

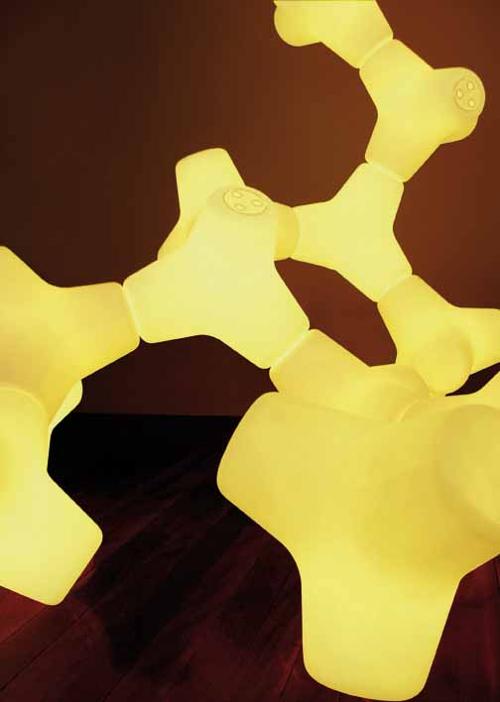

Smart Works, Design and the Handmade by Grace Cochrane is in many respects an exemplary book of an exemplary exhibition at the Powerhouse Museum. As she states at the outset, Smart Works is about 'design that reflects the values of the handmade'. There are 40 individuals and groups represented across the categories of jewellery and metalwork, ceramics, glass and resin, fashion and textiles, and furniture. Although the primary connecting thread is design for production, this encompasses a truly diverse range of approaches from studio-based craft to limited edition and larger production runs, and from totally hand-crafted to high-tech manufacture.

Essays by Cochrane and by Ewan McEoin provide a global perspective on issues facing designer-makers who are attempting the transition from studio practice to design for production. There is a pervasive cautionary note of interesting (read challenging) times ahead for craft and design. This quickly deflated my exultation in the wonders of Pippin Drysdale's ceramics and brought me plummeting back into the real-politik of the Big Brother world of art bureaucracy. 'It (the craft and design sector) must find a place of relevance in the post industrial, high-tech, information-centred society' states Visual Arts Board head Anna Waldmann in her foreword, with just a hint of the iron hand in the velvet glove.

Relevance, it seems, equates with attracting funding. The lavish VAB funding of Smart Works and of Object's similarly design oriented exhibition Freestyle, New Australian Design for Living points to endorsement of a top-down agenda to re-badge craft as a sub-category of product design. Is smart design the only way forward for the makers of handmade objects if they want to be relevant? Such a scenario relegates makers of one-off art objects like Pippin Drysdale to the margins. This is not to suggest for a moment that Grace Cochrane is espousing such an either/or position. In fact, she wrote the foreword for Snell's Lines of Site. Nevertheless, the relentless push towards design priorities of exhibitions like Smart Works and Freestyle diverts attention from the reality that in Australia today there is a greater concentration than ever before of truly superb jewellers, glass artists and ceramists, ie makers of handmade one-off objects, and they are attaining more recognition in the international arena than designers of so-called smart products (with the often cited exception of Marc Newson). On a positive note, the appointment last year of Ted Snell as Chair of the Visual Arts Board is a hopeful sign that sanity will prevail.