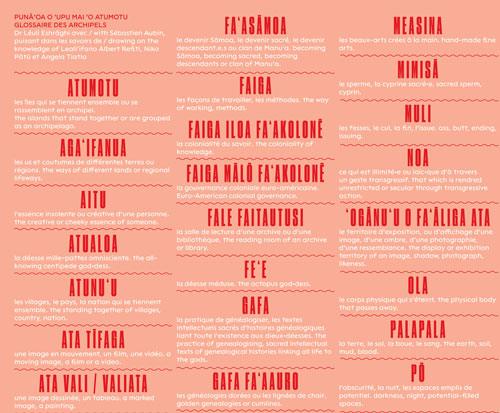

In this edition of Artlink, we consider Ancestral materiality, intellectual traditions and expressions spanning the great oceans, skies and lands connecting the kin and Country of First Peoples from around the world. We see the artistic, economic and cultural paradigms as a reflection on life and death, on black holes and shining stars illuminated as constellations in the night skies from the times of our Ancestors and traced in the footprints made on the lands we travel. In so doing, we ardently love and connect with our kin, known and not-yet-known, human and beyond-human, recognising commonalities and differences as we fight for the continuation of cultural practices. Extending outwards from Australia, we consider Ancestral memory, temporality and being through languages, waters and futures that are living and expansive.

In a world where many things are changing, care for Country, care for body, and care for creativity is what will keep us going. When we planted the seed for Artlink Indigenous Kin Constellations, it was our connections to kin across the world, demonstrated through our diversity, strength and languages as First Peoples, that we wanted to highlight. In the midst of COVID-19, life as we know it has changed forever. Across the world we all have an equal goal to survive in health, be generous and caring in the present time of great unknowns, fears and anxieties but also possible futures as an improvement on what we can currently imagine. The forced isolation of the world has allowed us time for reflection on how we live, work, consume and treat ourselves.

Hannah Brontë, a Yaegel and Wakka Wakka artist based in Brisbane posted the following text-based work on her Instagram (the meeting place, cooking channel, art gallery, library, museum and Saturday club in Corona times): “Now that You are Trapped On Planet You, Do you Like the Eco system?”

This is a prescient reminder that sometimes we let capitalist life get in the way of connecting to our deepest being and consciousness. The expansive globetrotter life can be “reduced” to our neighbourhood in a matter of weeks, teaching us to once more tread lightly and with gratitude. Has the world become so disembodied, so dissociated, from itself—and by extension the worlds of First Peoples—that we can’t sit with ourselves in the moment, and truly appreciate what we have become, and what distance we must traverse to return to the balanced, Earth-centred worlds of our Ancestors?

How can we move forward in a more grounded, simpler, healthier way? What kind of new caring political order can we create to ensure that those working in essential services such as health, education, food, knowledge and cultural life are appreciated, and the benefits better distributed, as we move to a sustainable low-growth economy, not reliant on the excesses of consumer capitalism, anthropocentricism and the fossil-fuel industries that have brought our civilisation to the brink of utter collapse?

Now is a time in which creative constellations that rotate and interrelate can provide dynamic spaces for relief and healing; escaping into an artwork or being moved by a text can be the highlight or saviour of the day or night. The ways we consume and digest have shifted and are slowing down, so that we are reading more, talking, painting, crafting, drawing, moving and using our creativity and our capacity for genuine care with purpose. The many forms of cultural expression have also shifted to extensive digital experiences, with the availability of the internet – a luxury, we appreciate, is not so readily accessible to the majority of peoples on this Earth.

The relational experience of viewing film, sitting with text or meditating on visual art through a screen will never replace the tangibility of space – of being in the presence of a performer, a storyteller, a master artist or a poet reading their own work at a writers’ festival. But the digital constellation is where our connections are evolving into a new era of art and making; for First Nations peoples, our cultures and practices on these platforms are integral to forging on.

Profiled in this edition of Artlink, the Unbound Collective conclude their Sovereign Acts series with moving realisations and reflections on grieving, healing states of being and knowing, building on the significant visionary work they have achieved in returning love and dignity to Ancestors whose incomplete memory sits unsettled in Australian colonial archives and museum collections. With Drs Lou Bennett and Romaine Moreton, we learn to see, feel, touch and smell the murnong-growing regions of “south-eastern Australia” via the quest for a rematriation of language and Country. With new-found reverence for this very special of Ancestor plants and the continuing Indigenous historical texts held within the land itself we come to consider how Western structures of “colonial coding” relating to Country can be dismantled.

Delving with care into the wahi pana, storied landscapes, of the sacred island Kahoʻolawe with Kanaka ʻŌiwi custodians and artists, Josh Tengan and Drew Kahuʻāina Broderick impart renewed understanding of the Indigenous ceremonies, celestial navigation and knowledge systems that surpass militourist control to connect the Hawaiian Islands to Tahiti, Te Ika a Māui, and further, beyond the present US occupation. Struggles for Indigenous lands and lives reach us from Sápmi in “northern Europe” in the generous portrait by Irene Snarby of pioneering senior Sámi artist and Duodji master Perisak Juuso whose cultural memory of Sámi territories, languages and seasonal mobility inform his numerous artistic innovations.

In a transcontinental interview, Kathleen Ash-Milby, Maia Nuku and Nigel Borell gift us stories of learning and experiences that have transformed their practices as Indigenous curators working in major art museums in Turtle Island and Aotearoa. Zoe Rimmer and Theresa Sainty poetically explore the indelible relationship to Country and culture of Pakana art-making practices and palawa kani language, detailing stories of creation Ancestors and the new generations now speaking language. In Karu’kinka, across the Great Ocean from lutruwita, Rebecca Carland recounts the incredible journey of cultural reconnection she and Camila Marambio have fostered between Yaghan communities in Santiago, Chile, and their Ancestral belongings long-dormant in Museums Victoria Collections in Melbourne.

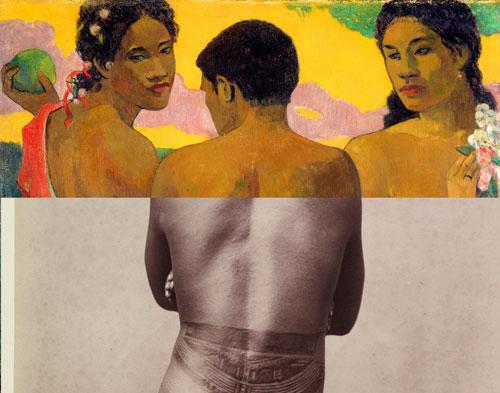

We are thrilled to share further reflections on compelling practices that include language work, humour, suburbia, and the Indigenous renaissance in song- and image-making, with Inuit artists Darcie Berhardt and Kablusiak profiled by asinnajaq, Polaris 2019 Award winner Wolastoqey singer-composer, Jeremy Dutcher, profiled by rudi aker, and Japanese–Sāmoan artist Yuki Kihara, representing Aotearoa at the next Venice Biennale (now rescheduled for 2022), profiled by Ioana Gordon-Smith. Visual and spoken sovereignty is also shared by Brendan Kennedy, connecting Mother Earth and language in a song and an exuberant painting with messages of care and warning.

Shell-sharing exchanges and ceremonies underlying Sarah Biscarra Dilley’s work from yak tityu tityu yak tiłhini territory in turn refuse waves of colonial dispossession in “central California.” Belinda Briggs takes us on a journey further upstream on Dungala (Murray) River, with lauded Yorta Yorta artists Jack Anselmi and Aunty Cynthia Hardie, who skilfully work clay into poetic ceramic forms that honour the shell middens and the cultural knowledges held in Woka (land).

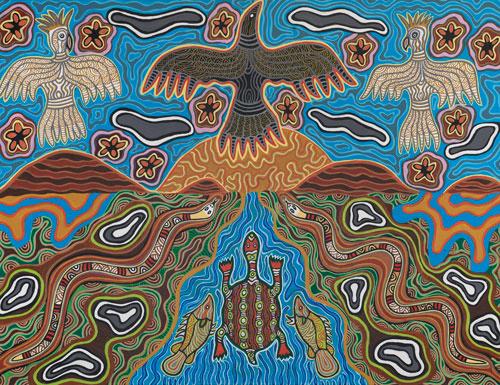

Freja Carmichael in turn tells a powerful hxstory of Indigenous fibre knowledges and careful tending to territories spanning the shores of the Great Ocean, through ungaire, buckie rush, black palm and red cedar, with Bundjalung artist Kylie Caldwell, Sḵwx̱wú7mesh, Stó:lō, Irish, Métis, Kanaka ʻŌiwi, Swiss artist T’uy’t’tanat-Cease Wyss, and Kuku Yalinji artist Delissa Walker. Coming from the North, Clothilde Bullen’s beautiful profile on senior Madarrpa artist Noŋgirrŋa Marawili and Mangalili artist Naminapu Maymuru-White conveys the importance of continuing Yolŋu moiety- and place-derived responsibilities for hxstories highlighting their continued innovation of visual languages depicting storied places in both painters’ œuvres.

Since the early start to the devastating bushfire season across Australia, we have moved in calamitous waves from fire, floods to disease, and from criminal deaths in custody to judicial and political collusion with tax-evading fossil fuel corporations, particularly on Wangan and Jagalingou Country by Adani, and in Wet’suwet’en sovereign territories by Coastal Gaslink. In this protracted indoor isolation time, Emily Johnson and Karyn Recollet bring vignettes from recent fireside gatherings on Lenapehoking territory, where they share kinstillatory methods of connection and world-making, including food, story, drumming beneath the starlit sky, and that key purificatory Indigenous practice in so many cultures—fire. Now, more than ever, we can shift alliances back to Earth-centred worlds that have been suppressed or dormant, and yet offer vital Indigenous sovereignty, as worlds of balance and reciprocity, waiting to be nurtured once more.

We invite you to sit with the generous voices, hxstories and knowledges shared in each of the commissioned texts. We hope you, like us, take much solace and inspiration to tread lighter and care more deeply for these—our cherished practices—of creativity, ceremony, being on land and living our ways, beyond the devastating colonial realities, to prepare for the challenges ahead for all living beings on our planet.

Multiple recent publications that we recognise, and that provide welcome perspective and momentum for the necessary rebalancing of our societies, include Becoming Our Future: Global Indigenous Curatorial Practice (2020), edited by Julie Nagam, Carly Lane and Megan Tamati-Quennel; Sovereign Words: Indigenous Art, Curation and Criticism (2018), edited by Katya García-Antón; and the artist book NIRIN NGAAY (2020), handmade by printmakers Trent Walters and Stuart Geddes, and edited by Brook Andrew and Jessyca Hutchens for the 22nd Biennale of Sydney.

Our cultures as First Peoples are inherent, not a choice – no more so than our first breath of air. We do not decide to “be” Indigenous peoples, we cannot choose to connect to the lands and waters we are responsible for, or our languages that encompass and enable our being in relationship with all of creation. In the cities or the bush – on concrete and atolls, the tundras and prairies, that vast chasm between the stars and the dirt, the in-between is all of us – the relational space of kinship is tangible, thick in the air that surrounds us, separates us and brings us together.

Rivers, rains and the Great Ocean flow through our veins keeping our hearts pumping and our ceremonies possible, the great mountains and plains, creeks and sand hills of Country make strong our bones, and keep supple and porous our skin, so that the winds and our smoking ceremonies can permeate to cleanse our souls and hold us, grounded where we are, and where we need to go in the futures already designed by our Ancestors before us.