A man dressed in a football jersey enters the very small kitchen of an apartment and begins to dance flamenco. The camera filming him is situated high in the corner of the room, emphasising the close quarters in which the dancer has to work. He begins to measure the room through dramatic gesture: opening a cupboard, flicking on the tap, resting his open palm on the hot plate, confronting the contents of the fridge. His feet rhythmically stomp, or tap at unimaginable speed.

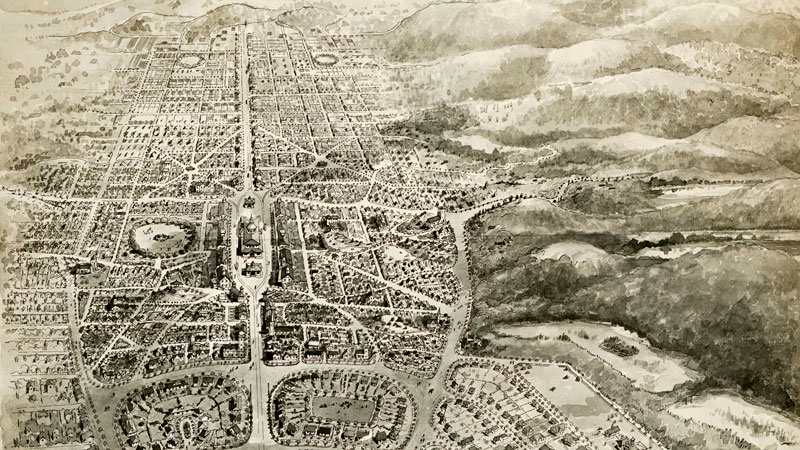

The dancer is Israel Galván and the excerpt of his 2006 collaboration with Pedro G. Romero, La Casa, is presented as a window, a momentary detour within another video work, The Housing Question (2019). A collaboration between artists Helen Grace and Narelle Jubelin with sound artist Sherre DeLys, the video focuses on Harry and Penelope Seidler’s house in Killara, Sydney (1967) and Casa Huarte (1966) in Madrid by José Antonio Corrales and Ramón Vázquez Molezún. Both the Australian and Spanish architects aspired to contribute to more equitable societies through high quality mass housing. The video connects the personal with the political by drawing on both intimate footage and historical documentation from each house and beyond, in order to explore housing, safety and security, and is presented as part of this exhibition of the same name curated by Julie Ewington.

Romero is quoted in the film as saying, “In the dynamics of land speculation, who plays the free market? Has it improved the functionality of the windows and doors? … We can only point to it, mark with a dance, a dance that measures the space.” The video work The Housing Question, and the broader exhibition, can also be seen as a dance tracing the intersections between intimate experiences of home, historical approaches to architecture and planning, and broader contemporary questions around housing. Its title is taken from Friedrich Engel’s 1872 texts regarding housing shortages in Germany, and a century and a half later Engel’s questions around basic human rights to secure, affordable housing remain ever pertinent.

The video is constructed on a foundation of four sections which take what Ewington terms “specific geometries” as their starting point: the radial, the square, the oval and the fabricated. While each of these has a particular relationship with elements of mass housing, modernist architecture, art and design, the work takes the viewer on a kind of dérive through these intersecting ideas. In its studies of the two modernist homes, The Housing Question moves between close-ups of textures, scenes showing Jubelin writing on the windows, and shots panning out of windows and skylights to surrounding foliage and suburbia beyond. A slow walk towards the Killara house is intercut with trippy moments of figures running through doorways. At other times the camera follows Jubelin from above, and in one scene it moves through a basement following parallel rows of pipes along the wall like staves in a musical score.

Modernist homes were sometimes used as testing grounds by architects experimenting with materials which could then be expanded into use in mass housing, and while Australia and Spain in the mid-twentieth century may seem poles apart, both democracies and fascist dictatorships were in agreement at the time as to the importance of social housing. The film presents footage of Corrales’ mid-century Spanish mass housing project alongside the voices of those currently protesting the removal of public housing from inner Sydney. Images of a Walter Gropius-designed housing estate in Germany are overlaid with audio describing how the provision of new homes in Lithgow, NSW “may prevent the formation of an army corps of anarchists in the next generation.”

Plans and photos of mass housing developments are juxtaposed with striking shots of Za’atari Refugee Camp in Jordan and Sahrawi Refugee Camp in Algeria. Sound artist Sherre DeLys drew on her sound banks of refugee and asylum seeker stories in composing the soundtrack for The Housing Question, and the interweaving of their stories with images of the work of Seidler (who himself was a refugee) are another complex thread.

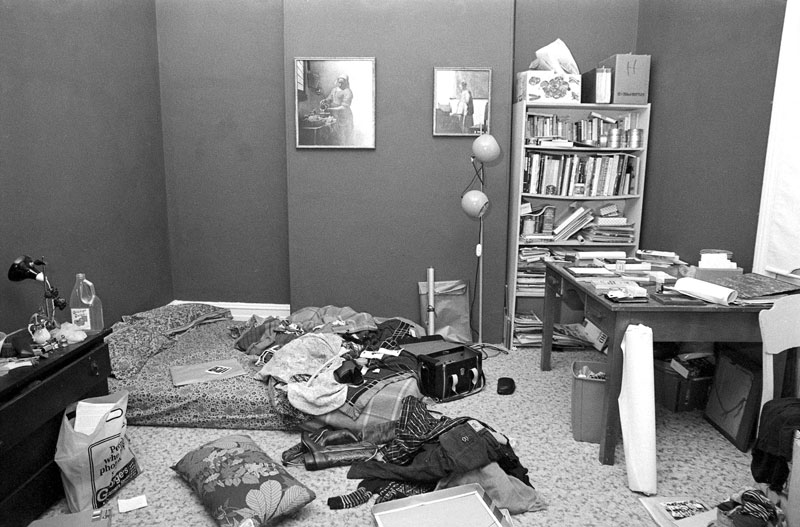

While The Housing Question film is the centrepiece of its namesake exhibition, it is by no means the totality of it. Rather, Ewington has used it as a starting point, presenting a number of works by Jubelin, Grace, DeLys and collaborators in a variety of media across the decades of their respective practices, as a mind-map in exhibition form. Helen Grace’s 1979 photographic series Christmas Dinner includes a triptych of photographs of a family sitting down for the annual feast. In each shot the photographer, and therefore the viewer, is positioned at the head of the table, surveying a surface surrounded by diners and crammed with dishes, with serving crockery jutting out at all angles. In the background a mirror hangs above a mantelpiece crammed with objects, against a wall whose orderly but busy wallpaper design contrasts with the chaos of dinner dishes in the foreground. In Christmas Dinner the house as an architectural design object paradoxically takes a back seat to the activity which is literally situated within it. In these small black and white photographs we see the house as a home—messy, busy and full of life.

Grace’s 1979–2019 work Living Arrangements 1949–2019 is a film generally devoid of inhabitants, comprised of black and white photographic documentation of the artist’s houses over time. It is overlaid with a soundtrack which gently introduces a living element through audio snippets contemporaneous to the still images. Presented opposite Living Arrangements in the Main Gallery is At the House (1987–2019), a cloud of images documenting a protest in favour of women’s refuges, the photographs increasing then decreasing in scale as they move through time and space. The absence of housing and the crowd of people stand in contrast to the quiet domestic scenes in Living Arrangements. The haircuts and clothes of the women and children in At the House recall a particular moment in history but the protest mode and motivation is as profound and relevant as ever.

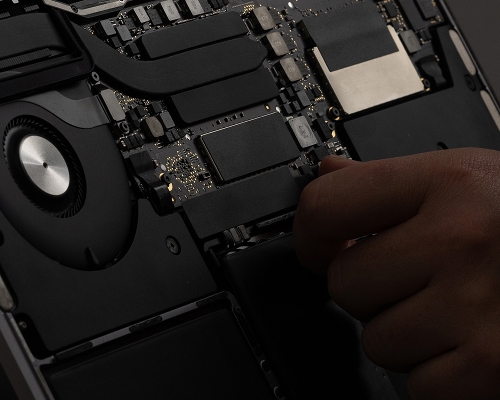

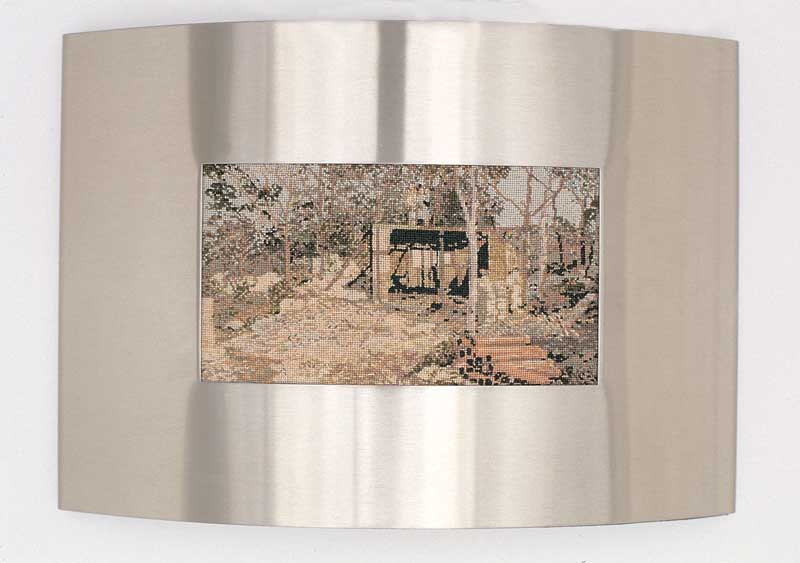

Across the courtyard, Jubelin’s petit-points are displayed on Margo Lewers’ shelving structure at one end of Ancher House. The suite titled Owner Builder of Modern (California) House (2000–01) depicts the construction of Jubelin’s family home in 1964 in suburban Sydney. While they are painstakingly made in a craft tradition and are presented like framed family photographs on a mantelpiece, rather than depicting an idyllic domestic life these works show the house in varying stages of construction, complete with exposed beams, cement mixers, and children playing where walls are yet to be built. The source photographs for these works are presented opposite these at the far end of the room in the form of a PowerPoint projection called Ilford (horizontal) (2008), named for Jubelin’s father’s preferred brand of film on which the images were originally printed.

Jubelin’s petit-points are made in response to her own family’s archive and history but also in response to the work of Josef and Anni Albers. (The former taught Seidler at Black Mountain College and the Albers and Seidlers were close professionally and personally.) In the main gallery, Josef Albers’ wool tapestry Homage to the Square (c. 1970) (which recalls a similar painting hanging in the Killara house in the film) is hung reversed, revealing the knotty, stringy hidden labour behind it, and Jubelin has made a work in homage to a detail of this work (Homage (As Yet Untitled [Josef Albers, c.1970], 2019). In the Lounge Room, Jubelin’s 2015 petit-point As Yet Untitled (Anni Albers, 1925) sits alongside the artist’s bronze sculpture Untitled 5 (Madrid) (2016).

This work is one of a series dotted throughout the exhibition (mainly on plinths, but also vertically mounted on a wall outside Ancher House) which are cast from pressed paper packaging which Jubelin collected around the world. These humble objects, made to be discarded, are literally and conceptually inverted and given a weighty permanence by Jubelin, transformed from mass-manufactured mouldings designed to protect contents far more valuable than themselves, into unique bronze sculptures. They are raw, unwaxed, sometimes patinated in black, and their irregular geometric forms and roughness simultaneously evoke a crowded urban grittiness and mediaeval stone castellation.

While the exhibition has documentation at its core, each artist’s exploration and interpretation of documentation and the archive is key to The Housing Question reaching far beyond those origins—Jubelin’s hard bronzes and soft petit-points, Grace’s cloud of protest images and streams of quotidian snippets. The Housing Question, both the film and the exhibition in its entirety, have a richly woven aesthetic which draw on domesticity and architecture, the overarching fundamentals and the minutiae.

Ancher House and Lewers House themselves, now a museum and no longer a home, become vitrines in which the exhibition is housed. The nature of modernist architecture and of vitrines is all angles and hard edges, but just as the foliage visible through large windows in the garden outside provides a soft counterpoint to all the right-angles, DeLys’ soundtrack to the film, and her other sound works, provide a bridge of softness, through invoking breath and the body through time.

The Housing Question perhaps resides here. Where is the body situated in this complex scenario? As Architect, Builder, Homemaker, Inhabitant, Immigrant, Aspirant? The competing motivations of each of these co-dependent protagonists are what make The Housing Question so pertinent, and so fraught. At a time when questions are becoming more and more pressing around securely housing an increasingly shifting and precarious global population, this exhibition, and the video work at its core, looks to key moments in the past in order to better understand the dilemmas of the future.