Strange turns of whimsy and oddities of form populate Bathurst Regional Art Gallery’s group exhibition Curiouser and Curiouser curated by Julian Woods, the title taken from a line in Lewis Carroll’s much-loved children’s novel, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Several of the works function as an updated Illustrated Alice. In Fall Stack (2012) Kate Mitchell is unashamedly literal in her reference to Alice’s fall down the rabbit hole. But here, instead of the White Rabbit’s amply stocked larder, it is a view of endless shop fronts with awnings that we pass by on the way down. Jason Sim, by contrast, uses neon tubes and mirrors to create architectural tricks of perception. Viewers peering into the vortex of his Shelf Space XV (2018) experienced the illusion of infinite depth.

Most of the works in the exhibition share a looser allegiance to Alice’s experiences, replacing the inherent contrariness of the book with a deviant imagination, as demonstrated in the Surrealist-infused performance by Junkyard Circus channeling the scene Dali created for Hitchcock’s Vertigo featuring a hula hoop dancer covered with strange drawings of eyes, alongside Kimberley Liddle’s In A Dream (2018), which recalls the human candelabras in the chateau corridors of Jean Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast. Many works, like the oversized macramé polyhedrons of Nike Savvas’ Sliding Ladder: Truncated Icosahedron #1 (2010), Louise Paramor’s overdone Boomtown #2 (2016) and the fractured psychedelic planes of Adrian de Giogio’s Chameleon(2018), also channel the excesses and decorative redundancy of the novel’s Victorian origins, making the exhibition an occasion to celebrate the kind of maximalist aesthetics that Nick Cave has championed in his concurrent major series of installations at Carriageworks.

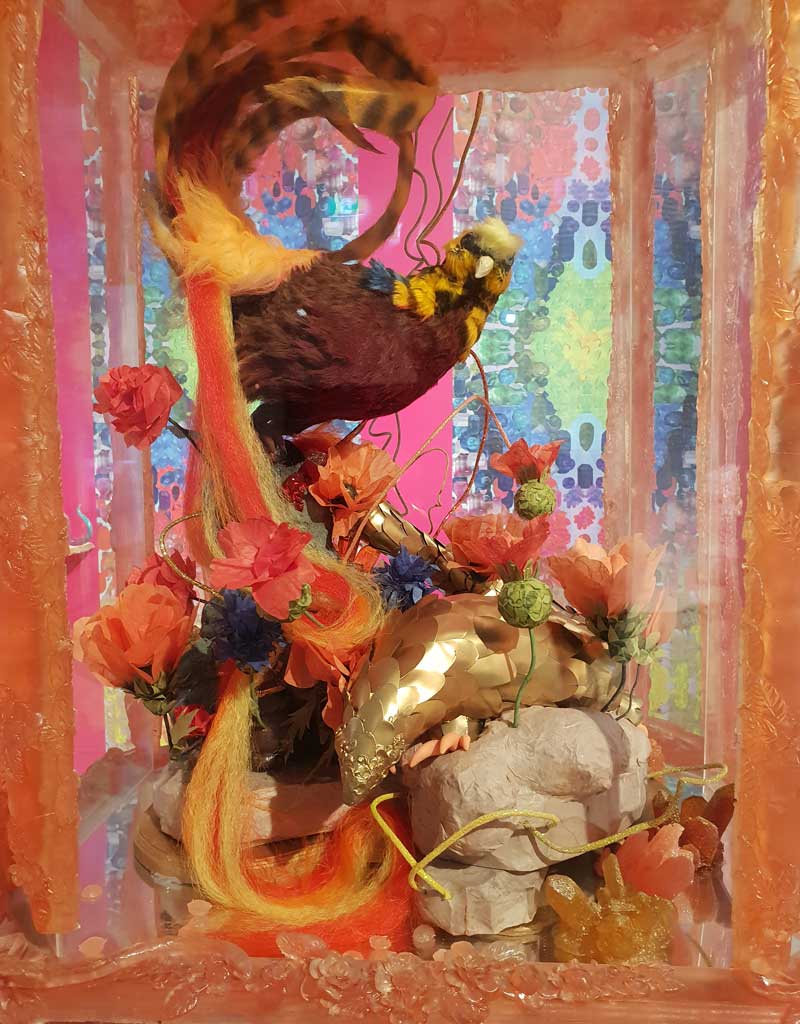

The influence of John Tenniel’s depictions of Carroll’s fantastical menagerie of animals, including the Dodo, the Gryphon and the Mock Turtle (a pictorial composite of the ingredients of Mock Turtle soup) can be discerned in the fanciful compositions of Kate Rodhe, such as Kate Rohde’s Pheasant and Golden Pangolin (2007) and Rabbit Vase (2016), a posy of orange baby rabbits, carrots and fragments of coral. Cast in technicolour resins and installed against the pulsations of Rodhe’s equally intense op-art wallpaper, Rodhe’s arrangements and creations also recall the fantastical transformations of the horses that turn to stone in A Thousand and One Nights.

In one of many other works of hybrid animalia, Troy Emery’s Saint Euphemia 11, appears to cross the offspring of a polar bear with the Cookie Monster, mimicking the display of unique and unusual specimens in nineteenth century museums of natural history. Standing tall on its hind legs, in order better impress with its scale, Emery’s bear stands sentinel in the manner of a pop-cultural mutant as witness. Fanciful but not necessarily reassuring, in its purple and pink sugarcoating, the viewer is drawn the viewer into the less aleatory realm of scientific perversion in tampering with nature.

Further crossing issues of scale with curious and sometimes confronting and behavior on this side of illogic, Nell’s Buddhist-inflected prayer to the giant fly in her performance video Summer (2012), is followed by a violent attack with a cricket bat. Michaela Gleave, in her 7 Hour Balloon Work (video documentation of performance) (2010), is equally contradictory in expending her breath to inflate a roomful of balloons that she then destroys by popping them. Rosie Deacon’s more whimsical Kangasue (2017) manifesting as a giant kangaroo, places the gallery-goer in the role of Alice’s shrunken self ![]() about the right height to poke out of the marsupial’s pouch.

about the right height to poke out of the marsupial’s pouch.

Nonetheless, on balance, the darker works carry. Violence is inherent in Natalie Ryan’s Pretty in Pink (Goat Head) (2009) – she is, after all, exhibiting a severed head as a trophy, and the tail-less cheetah in International Klein Blue, and ear-less rabbit in deep moss green (the shade of rotting lettuce), evoke further thoughts of mutation. Amanda Wolf’s stage props and masks, in Hide and Seek (2018), resemble the set of a children’s pantomime in borrowing motifs from the wallpaper, but like the pattern which eventually consumes the beholder in the Victorian novella by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, The Yellow Wallpaper, the impact is as anxiety-inducing as it is playful.

The luminous works in the darkened spaces, though enchanting, also provoke ambivalent unease. The radiant clusters of Karen Golland’s Mad Honey (2018) could easily be mistaken for a crop of psychotropic botanicals and suggestively recalls the scene from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland of the hookah-smoking caterpillar atop the giant mushroom she is instructed to nibble. “One side will make you grow taller, and the other side will make you grow shorter.” The room notes redirect the viewer’s attention to the bees that may have been making honey in azalea gardens of dangerous hallucinatory toxicity in Hakone, Japan. As frequently stated in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland things are often not what they seem, and visual attraction can hide perilous consequences.

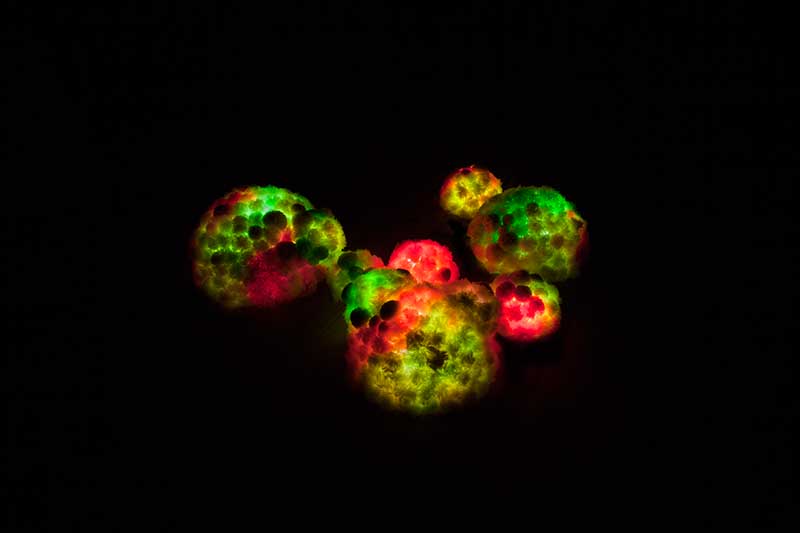

As a further instance of this, the floral specimens of Tracy Sarroff’s Rhizopoda Radiaria Domes (2008), glowing like attractive poison, are also possibly lethal. Alluding to the natural marvel of bioluminescence, but equally to the science of genetic modifications, these hybrid plants, like the mutant animals of Emery and Ryan, exhibit a darker aspect of wonder. Last in the trilogy of the nightglow works, Ella Barclay’s Summoning the Nereid Nerdz (2015) revisions the witches’ cauldron from Macbeth as a liquid nitrogen bath giving off garish fumes. Wiry, blackened protrusions emerge from the bath and align experimentation with the dark arts of sorcery and superstition.

It is also difficult to accept the charming anomaly of Tully Arnot’s Sanctuary (2018) in which delicate butterflies flutter their taxidermy wings from their robotic torsos. Viewed through this darker context his mechanical hybrids herald a world gone awry, and, further, anticipate extinction like Carroll’s pontificating Dodo. Pia Van Gelder’s You or Me (2011) is likewise perturbing, signaling the glitches inherent in our increasingly algorithm driven universe. With one camera pointed at the viewer and another back at the screen itself, the system malfunctions as a result of monitor’s attempts to obey two contradictory commands.

This revealing malfunction might prompt a viewer to puzzle over what the exhibition as a whole sets out to achieve. Competing for attention like the characters in Lewis Carroll’s eloquent and playful prose, in the midst of as much contrariness as curiousity, I did wonder if the individual works would have had more useful conversations in a tighter-knit display. And, were a moral to be drawn from Curiouser and Curiouser – as the Duchess in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland insists, “Every thing’s got a moral, if only you can find it” – where, indeed, would one look? Certainly, there is much to draw on in contemplating as cautionary observations the darker edge of species loss, bioengineered hybridity and technological innovation in this exhibition’s bizarre imaginings.