.jpg)

In Sarah Hall’s novel The Carhullan Army (2007), Sister tells of her transformation into a warrior. She and other women fight the Authority, a repressive regime ascending out of a near-future England besieged by catastrophic sea-level rises. Collective trauma experienced in “the collapse” begets insurgency. Sister notes her own shaved head, muscular body and tautness as “the anatomy of a fanatic”.

Emotional trauma as a catalyst for adaptation and resilience is an enduring topos of post-apocalypse centred literature. The Road (Cormac McCarthy, 2006), Things We Didn’t See Coming (Steven Amsterdam, 2010) and After the Apocalypse (Maureen McHugh, 2011) are a few examples, each dealing with versions of environmental catastrophe. Championing this phenomenon, in Colson Whitehead’s Zone One (2011) the narrator Mark Spitz tells us of PASD (Post-Apocalypse Stress Disorder), describing the vast galaxy of survivor dysfunction around him, with “its sundry tics, fugues and existential fevers”.

Jessie Boylan’s moving-image installation Rupture has a subtle literary-narrative texture, with a protagonist and a poetic accompaniment of intense, disruptive images. Spending time immersed in Rupture is to encounter something like Whitehead’s “tics, fugues and existential fevers”, but the work doesn’t get mired in that boggy zone of despair. While Boylan’s powerful imagery, in a tight dance with an unsettling audio track, draws attention to the fragility of connections between the human body and the natural environment that nurtures it, it also quietly suggests the strength and potential of that relationship without being didactic.

Boylan has described her work in general as an investigation into how we live amid the imminent possibility of environmental and social disasters. Using documentary footage, still photography, sound and light, she has researched communities affected by disasters as diverse as climate change, biodiversity loss, mining, flood, fire and drought. She has also, for the exceptionally well-crafted Rupture, consulted with a trauma-informed psychotherapist and drawn on the talent of performance artist Virginia Barratt, whose eloquent form features in the six-channel video and sound installation. In an essay about Rupture, Jacqueline Millner writes that Boylan’s artistic development has been “continuously attuned to mounting social, political and environmental anxiety”. She tells us, too, that Barratt has for many years used her own body as her “material” – the site of research about panic attacks.

As well as Barratt and Jenna Tuke (the psychotherapist), Boylan has collaborated with digital artist Linda Dement for Rupture. Boylan says the work explores the ways in which the body and the world mimic each other in modes of panic and crisis, how bodily symptoms are an “appropriate response to personal traumas and global catastrophe”. She gives us this robust imagery and the under-the-skin soundtrack on a thirteen-minute film with a subtle crossover from closing to beginning; it is easy to remain with the work, loop after loop.

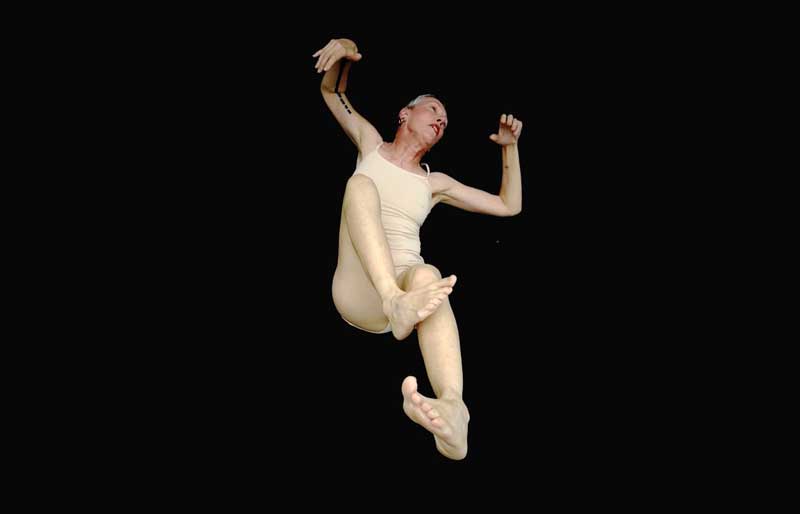

There are six screens, five of which are loosely arranged in a sort of bower within which viewers may sit. Three screens feature a woman (Barratt) in pale undergarments, her form somewhat reminiscent of Eadweard Muybridge’s motion photography stills. The other three screens display successive shots of a chaotic natural world (fire, deluge, storm) interspersed with data and fragments of long strings of text drawn from what might be scientific reports or studies. With some wryness (perhaps unintentional) the piece uses the same techniques as the televised news broadcasts that can instil such anxiety in us: emotive soundtrack, alarming imagery, relentless pace. Yet, within this stream of images, there are also more calming elements: an intriguing scene of a silhouette of hills graced with a strong electric aura (possibly a suggestion of country as spirit/soul) billowing smoke, and gently falling rain.

Of those screens featuring Barratt, the first, like a standing mirror, greets us at the entrance to Rupture through a dimly-lit corridor. This slightly moving image is our calmed sentinel, quietly observing us from her stillness. Inside the room, a second screen is on the ceiling, featuring Barratt writhing slowly, almost as if she were free-falling, limbs flailing in a dreamlike dance. The third screen showing Barratt is set alongside the three nature-based screens, all in a gentle curve with the ceiling screen above.

It is this third Barratt screen that immediately captivates, for the sounds early on in the soundtrack (gasps, truncated sighs, barking exhalations and pulses) are laced with a panicky horror-sublime. Her gaze (upon what, when or where?) draws us in, but deflects. Like a Rorschach blot or a kaleidoscope, her shimmering image is sometimes doubled upon itself, even tripled, these ghostly echoes of her body glitching and pulsing. Her multiple limbs extend like those of the goddess Kali, destroyer of evil, in a twitchy sequence of movements that speak to me of distress, but also of transcendence, of connection to the natural world. Perhaps these dance-like gestures are therapeutic: synching with the chaotic environmental disasters on the other three screens, but also suggesting some sort of prevention, or intervention. For split seconds at a time she pulses out of a focus.

In her essay, Millner asks if tapping into bodily anxiety can connect us to the reality of the world in crisis – whether panic and anxiety can become “useful companions” that might “harbour insights about new ways to respond to global crisis”. Can we transform our rabbit-in-the-headlights response into concrete action? The psychological lacerations being exacted by the Anthropocene are at present impossible to fully map; they probably began with the Industrial Revolution, and who can tell how they will proceed. Both the recent report from the UN-backed Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warning that we have less than 12 years simply to limit the extent of the catastrophe underway, as well as the UN’s own report seem overwhelming. After all, it is beyond question that irreversible climate disruption is an emergency and that our leaders have failed us, miserably. While Boylan’s work seems to connect with this real terror it also seems to suggest that aligning with nature’s sublime strength may show the way forward.

Rebecca Solnit argues recently[1] for us to not concede defeat; we as individuals must set out “better options with all the passion, power and intelligence” we have. “A revolution is what we need, and we can begin by imagining and demanding it and doing what we can to try to realise it. Rather than waiting to see what happens, we can be what happens.” Boylan’s Rupture, rich with nuance and complexity but perhaps on the same trajectory as Solnit, might inspire this way of being. As we watch Barratt’s gestures move from a disturbing hand-wringing to an exquisite finger-tapping over her heart-centre, lightning-charged, we might feel uplifted.

.jpg)

Footnotes

- ^ Rebecca Solnit, “Don’t despair: The climate fight is only over if you think it is”, The Guardian, 14 October 2018: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/oct/14/climate-change-taking-action-rebecca-solnit?CMP=share_btn_link.