Private, Gowrie House, Stella Bowen’s painting of an unnamed young Second World War soldier has long been on display at the Australian War Memorial, but like the AASEAL barks that came into all state galleries without provenance in 1956 and which Margo Neal dubbed the “bastard barks”, it has always felt like an orphan.[1] Who was he? He was always thought to be an Aboriginal soldier, but the trail stopped there. Finally in 2014, in the lead-up to the centenary of Gallipoli, curators at the Australian War Memorial looked closely at the records of the POWs who passed through Gowrie House at Eastbourne in southern England to see who might have been of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent. A match with the soldier in the painting was finally made – Private David Harris – and a family photograph backed this up.

This deeply psychological painting, now supported by a wall text about Private David Harris, is one of the exhibits in a path-breaking new exhibition For Country, For Nation at the Australian War Memorial that looks at Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander military service in times of war and peace. The exhibition is a mix of works of art, archival photographs and material culture objects including military medals that families of the soldiers have donated. In recent years the AWM has been aggressively appointing and commissioning leading Aboriginal artists to represent a version of events totally absent from the record. In 2012 Tony Albert became the first official war artist to focus on the Australian Army's peacetime unit in the Top End known as NORFORCE. Many of the works on show in For Country, For Nation, acquired over the last few years along with work by six artists commissioned for this exhibition, tell a story as freshly as if yesterday based on the artists’ own recollections and stories that have been handed down within communities. But this is a version of wartime service that has not been a part of the Anzac tradition, and just as women had to elbow their way into this exclusionary and narrow national myth, now curators have turned their focus to another invisible group.

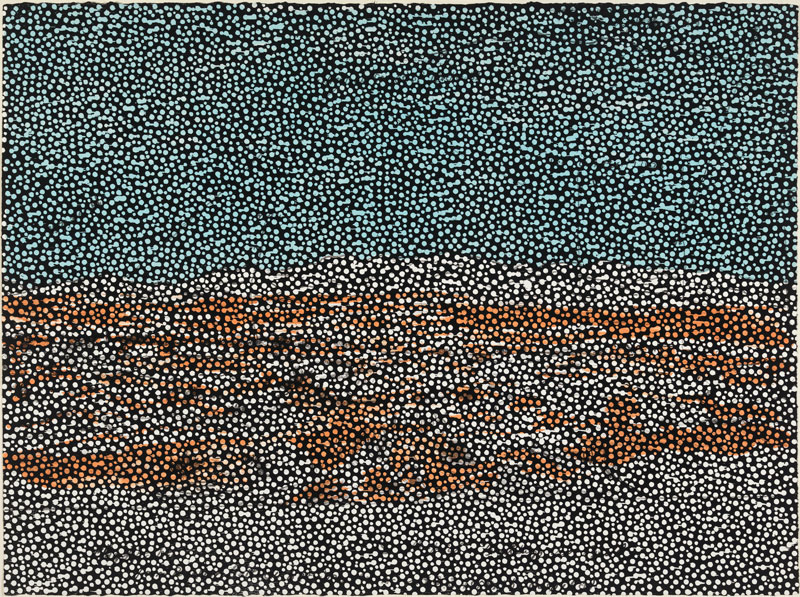

There is a long but little acknowledged tradition of military service within Aboriginal and Torres Straits Islander culture, and the photographs serve to establish that presence. The enduring legacy within Indigenous culture of serving one’s nation and the way this takes on local meaning comes through in artwork after artwork (52 in all) ranging from the Boer War through to the most recent of conflicts. Daniel Boyd, one of artists commissioned for the centenary of Anzac, discovered on delving into his family’s history that his great grandfather along with other family members had served in the First World War. He was only able to enlist in 1917 because he had an exemption from the Chief Protector of Aborigines; he joined the 11th Light Horse Regiment and served in Egypt. His regiment with their 30-plus Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander members was known affectionately as the Queensland Black Watch. In Untitled from the Anzac Centenary Print Portfolio (2015), Boyd overlays an iconography of Western Desert dotting onto a drawing by soldier–artist Otho Hewett, who sketched the battlefields near Magdhaba where his great grandfather served. The dotting both obscures the underlying landscape and provides glimpses into it, just as history has obscured the memory of how Boyd’s great grandfather was one of the 1,000 Indigenous soldiers in that war.

Megan Cope similarly reinscribed Private Richard Martin into the history of the same war in Ngaliya barwon Gami (our great uncle), 2014–15 by placing his portrait as a black ghostly presence behind a military map of the areas where he fought at Bullecourt, Messines and Passchendaele. Martin was one of seven Indigenous men from Stradbroke Island who enlisted, but he had to say he was a New Zealander to do so. Cope had grown up hearing family stories about her great uncle serving, and seeing his photo on the family’s mantelpiece, but as she said “not many people think about Aboriginal people being in Europe 100 years ago.”[2]

Gordon Bennett, meanwhile, tackled white man’s history head-on in Psychotopographical Landscape (Inversion) (1990). In his appropriation of the cover of a 1958 school reader “The story of Anzac,” a First World War classic that presented Charles Bean’s version of the Anzacs, Bennett shows black soldiers having disembarked at Gallipoli and charging into battle. In place of George Lambert’s green and browns employed in his painting recreating this scene, and in the collection of the Australian War Memorial, Bennett’s colours are those of the Aboriginal flag – red, yellow and black.

Numerous art works focus on top-end events in the Second World War such as senior Komaduh artist Jack Dale’s Japanese Bombing Roebuck Bay, Broome, 2003, which is based on his memory of the event as the wall text relays: “I was in Broome after a mob of cattle for the boat. I was twenty something. A bloke was yelling on the loudspeaker, ‘The Japs are coming.” The planes all came in at the same time. They had the red circle and the propeller on the front. They shot at the town first and then they got the water planes in the bay. They came back and shot at me and some poor buggers swimming in the bay. My mate Jim Kelly got his head shot off. He was running to get the battery to start up the truck I was hiding under. We just wanted to get out of there. There was bullets, bombs, everything. A lot of poor buggers got killed and drowned.” What Jack Dale does not recount is that some of those killed in the flying boats in the harbour were women and children just rescued from the Netherlands East Indies. Although some who died were non-Indigenous people, Dale shows their spirit returning in the traditional form of the snake.

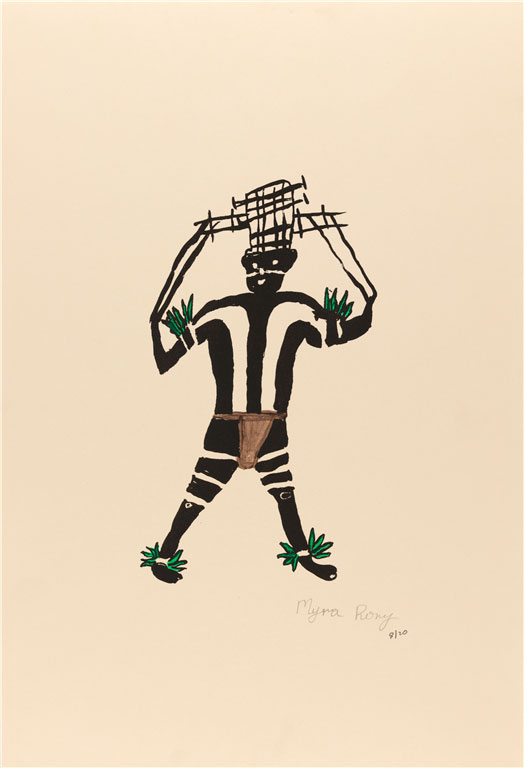

Meanwhile, for Yanyuwa artist Myra Rory of Borroloola in the Gulf of Carpentaria, the rescue by local people of the one surviving American pilot who crashed onto their land and walked for 140 days over 300 miles before being found has entered their folk lore. Myra Rory’s image Aeroplane dance (2007), or the Ka-wayawayama, shows a contemporary Yanyuwa dancer re-enacting the rescue. Many Aboriginal people were involved in the war across the country working in munitions factories, in shipyards and on farms as conscripted labour, which Sybil Craig and Emerson Curtis portrayed as official war artists in 1945, but art museums in recent decades have been turning to Central Arnhem Land Rembarrnga artist Paddy Fordham Wainburranga’s work from the 1980s for firsthand accounts of just such labour, and key moments of historical and social change. His bark in the exhibition World War II supply ships, Darwin (1991) showing Aboriginal men unloading supplies is based on his memory of the event, he was about 12 years of age at the time. His imagery is a melding of the realism of the occasion with iconography of mythic elements from his language group.

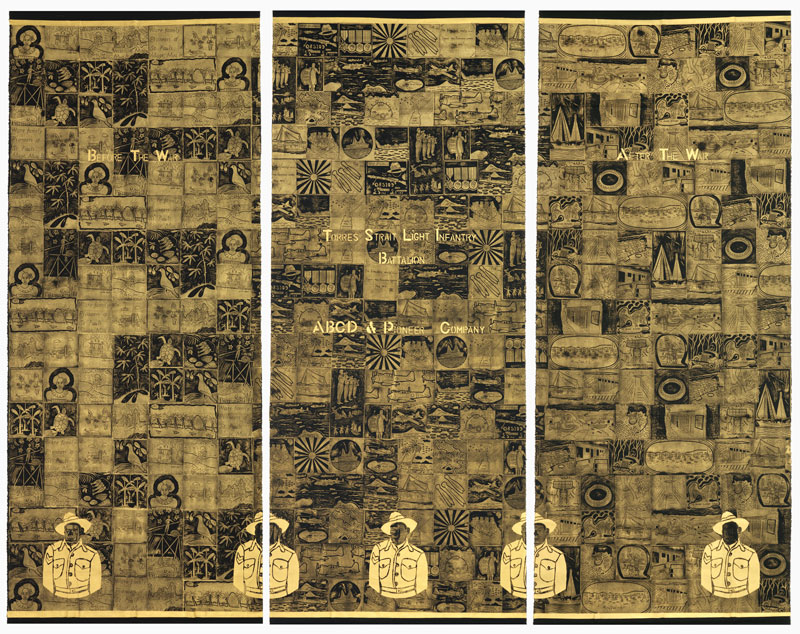

The Second World War was very real for people in the islands of the Torres Strait; they were close to New Guinea and came under attack. On Waiben (Thursday Island) large numbers of men enlisted, and the response of artist Rosie Ware, who is based on Thursday Island, in her commissioned triptych Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion (2014–15) reflects on the experiences of men like her father Elia Ware who joined up, and are shown in uniform, as well as the women left on the islands: “With my three cloths, it was about my dad, but mainly about my mum. She represents (on the cloths) all the other mums left behind on the outer Islands when my dad and all the Uncles volunteered and came into Thursday Island … The majority of Torres Strait Islander men left the Islands and they went enlisting for Australia, fighting for Australia … I wanted to show how hard it was for the women without the men around.”

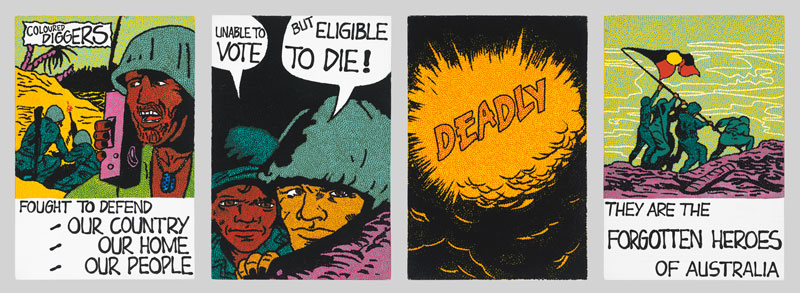

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander soldiers were paid less than their non-Aboriginal compatriots, and had to wait until 1962 for the right to vote. Artists Vicki West and Tony Albert have not let this pass by without critique. In Tasmania Aboriginal people on Cape Barren Island had to leave their land in 1951, while soldier settlement blocks were created on Flinders Island, but only for white soldiers. This issue of land rights is integral to much of West’s work: she is of the Trawlwoolway people, and her fragile kelp vest in Sentinel (2016) “pays homage to past ancestors who fought to protect Lutruwita [Tasmania] and the present-day cultural warriors who continue to fight to protect our home.” Tony Albert’s Coloured Diggers (2013), with it comic book style image and text is even more hard-hitting when it comes to the social and political inequalities the Indigenous soldiers faced on returning home after the war.

Rediscovering how to make the traditional implements involved in fighting for country, and the meaning embedded in such traditions, has much resonance in some Aboriginal communities today. Ngemba artist Andrew Snelgar’s commissioned shields and weapons in wattle, mulga and ironbark, inscribed in natural ochres, charcoal and resin, refer to the Two Brothers Creation Story and the long standing tradition of defending country.

Bronwyn Bancroft’s image Time Marches On (2010) shows her father Owen Bancroft marching as he did every Anzac Day with the 53rd Port Craft Company (of the Royal Australian Engineers) in George Street Sydney in 1985. He enlisted in the airforce and served in New Britain. Bronwyn Bancroft’s wall text explains: “Dad had a light blue coat on and I always remember how much he loved his mates and meeting up with them at the Newtown RSL. He was the only Aboriginal man in his division and they adored him. I once asked Dad why he went to war and he simply said, “It’s my country too.”

This is an exhibition to linger over and take time reading the wall texts that provide firsthand personal accounts and cultural memories, along with the supporting archival photographs. It is a curatorial mix, and while this can be problematic in some museum displays it works here: the artworks need the archival material to give depth to their already persuasive representational content. An exhibition space is, in essence, a Western construct of a museological display, but this carefully curated space honours Aboriginal people, inserts them as players in the national story and reclaims their history. At the entrance, Indigenous weavers Claire Bates and Glenda Nicholls set the scene with three woven shields for each of the armed services, while music from a digeridoo gently permeates the space. The strategy employed by lead curator Amanda Reynolds to include interpretive wall texts in the artists’ own words provides agency, and enriches the experience of the work. This exhibition is not recovering an art history; rather, it is constructing a visual history within a wider recent history that is still a work-in-progress. The shame is that it has taken this long. We now await the War Memorial’s encounter with the Frontier Wars given Rover Thomas’s painting Ruby Plains Massacre I (1985), has been recently acquired. The shocking irony is that such massacres continued in the 1920s even though Aboriginal people had served as patriotic citizens and fought for Country in the Boer War and the First World War.

Footnotes

- ^ The 1948 American-Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land (AASEAL) was one of the largest scientific and cultural expeditions mounted in Australia. The material collected was distributed to art galleries and museums in Australia and the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC. Cited from Margo Neal, ‘Charles Mountford and the “bastard barks”’, in Brought to Light: Australian Art 1850–1965 from the Queensland Art Gallery Collection, in Lynn Seear and Julie Ewington (eds), Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 1998, p. 312.

- ^ This quote, and subsequent quotes, come from wall text in the exhibition.