Just as performance art is entering the mainstream, Liveworks, born five years ago as the festival of live art, has begun calling itself a festival of "experimental" art. The term may be as problematic as “mainstream”, yet in this instance it allows Performance Space to curate work far beyond performance, such as Jonathon Jones's guguma guriin. Arguably, the grounding work of Liveworks, guguma guriin / black stump was installed for the entire duration.

The floor is covered in upended tree roots. From their twisted shapes, shadows grasp across the room. They are native White Cyprus, painted black, sourced from Jones’s ancestral Wiradjuri country. Pencil rubbings of cross-sections of felled European Cyprus grid one wall, echoing the lines of plantation timber. Uncle Stan Grant’s Amazing Grace, sung in Wiradjuri, provides a soundtrack. In the narrow gallery beyond, a video pans what seems to be a silhouetted horizon, yet is actually a digitally manipulated photograph of a Wiradjuri handtool bought by the artist on ebay. It is a powerful, haunting work whose shadows and dualities and central image of death resonate long afterwards. Yet I am still not sure how it fitted into the Liveworks festival as a whole.

The free performance program was consistently strong. Latai Taumoepeau’s Repatriate I & II, the latest in the artist’s durational performances addressing climate change, saw her enduring a slowly filling tank, while Repatriate II engaged in the Sisyphian task of moving ice. Both displayed the fiercest commitment and most finely tuned gestural vocabulary I have seen in a long time.

Dancing with Drones is the latest experiment in drone technology by Josephine Starrs and Leon Cmielewski in collaboration with dancer Alison Plevey. Aerial shots of Plevey in the landscape gave way to the dancer herself, as macrocosm to microcosm, foregrounding human vulnerability and the sinister side of surveillance. The drone itself, like an evil toy, hovered overhead momentarily, its double reflected in the ceiling.

Garth Knight, known for his photography, displayed his ropework skills in six mammoth installations constructed over five days, each with the nucleus of a large framed web containing blocks of sandstone. Knight deftly ensnared a different model each evening, concluding with a final act of suspension. Each installation was unique, responding to the body and strengths of the model. It was brave and timely curation to bring this aspect of Knight’s practice into the performance arena where it belongs. It made fascinating viewing, as much for the subtle interchange between roper and model, as the growing image.

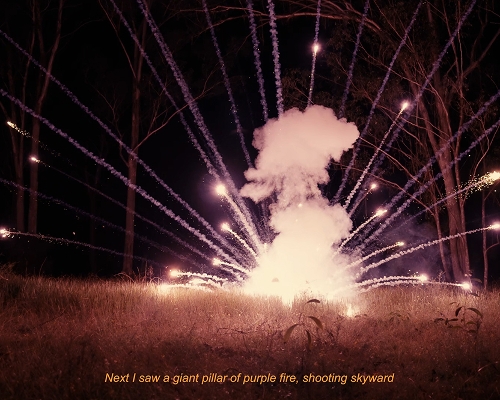

Up the other end of the foyer, Roslyn Helper and Harriet Gillies as Zin performed Each Other. With a Justin Timberlake tune on headphones, dressed in bright lycra, the duo danced with each other and any passers-by who cared to join. But, the work came across as trite, the choice of song the start of the problem. Hissy Fit’s I Might Blow Up Some Day was similarly underdone, despite a well- supported gestation.

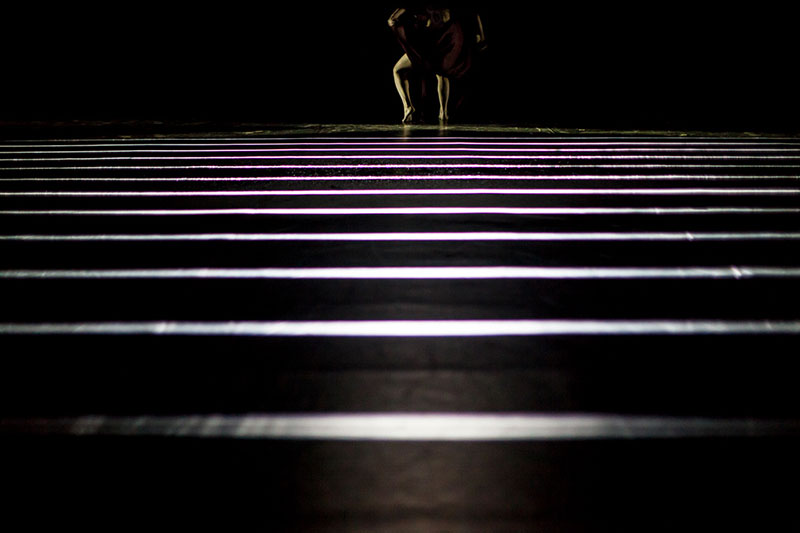

The ticket prices for this pointed to the biggest problem of the festival - one that bedevils most of Sydney. Who can afford $35 to see a troupe of new young artists test their mettle for 40 minutes? Not even I, a generation older. Eisa Jocson’s Death of a Pole Dancer / Macho Dancer was twice as long, as was Victoria Hunt’s Tangi Wai, yet all were ticketed equivalently. Tangi Wai is a monumental work that should tour internationally. The refined atunement of flesh, sound and light, conveying concepts both oblique and profound, showed Hunt to be in her prime.

For his performance lecture, Mike Parr showed videos that are still rivetting decades later. He read from his notebooks, most memorably a work entitled Nail Your Hand to a Tree, which gave great insight into the national condition. Parr is always a must see for his rigour, courage, madness and humour. Even so, at $20, the lectures were also overpriced.

An unlikely disrupter of performance art tropes was percussionist Bree van Reyk with Wall of Sound. A five minute one on one where you sat one metre from the performer yet barely saw her, for the massive cymbal suspended between your bodies. This she stroked from whisper to crashing climax, the instrument shimmering with sound and light, part avatar, part sculpture.

George (Poonkhin) Khut’s latest work Behind Your Eyes, Between Your Ears was a sort of digital neural portrait studio, with audience members wearing a brainwave sensor while attempting to calm their minds. The generated visuals were laid over film taken of the subject’s face; this was seen live, then replayed to the subject immediately afterwards during an interview. Khut’s most interesting work has possibly not taken place in art sites, but in Westmead Children’s Hospital where he has been honing technology for chronic pain relief. Yet to his credit, each iteration while gathering data, is engaging, aesthetic and immersive. Out in the foyer, Ghenoa Gela’s Mura Burai provided an ebullient counterpoint with her ensemble of dancers reinterpreting Viewpoints.

The name Liveworks is a UK concept, as the term live art was first coined there some decades ago to draw together dance, theatrical, visual and conceptual forms through the performing body. This can neglect edgier or subtler modes of performance art, as black box or white cube shows end up dominating the curatorial program. But a festival of performance art is so necessary here in Sydney, Carriageworks is an ideal venue. If Performance Space is to maintain its experimental charter, would they consider programming more action-based, gestural and conceptual work? Work testing duration and duress?

And while it was refreshing to see a Filipina artist featured, did she come only via European support? Would the grand elders of Asian performance art – Chumpon Apisuk, Wen Lee, Tari Ito – also be considered? Or even younger luminaries such as Lynn Lu? It seems to me that the most logical course would be to focus on the Asia-Pacific region, so rich in performance, yet still neglected internationally.