.jpg)

It's difficult to know where to start with the hugely problematic exhibition Australia at London’s Royal Academy of Arts. Setting aside its ambitious agenda to “tell the story of [Australia’s] art and history over more than two centuries of rapid and profound change,” and its desire to do this through landscape no less, there is the curatorial roll-call of Every Significant Australian Artist Ever; a heavy-handed, literal treatment of the notion of landscape as something singularly geographical; and a clunky, crowded, chronological hang. Does it “reveal the full breadth of the country’s art – Indigenous alongside non-Indigenous”? In a word, sadly, no. The remit, the hang, the over-reliance on painting, the tokenistic inclusions – they all collide in what amounts to a dense and disappointing experience and a pervading sense of frustration at such a missed opportunity as the first major survey of Australian art in London in over fifty years.

The exhibition opens with Shaun Gladwell’s video Return to Mundi Mundi. It’s the only work in the entire show to be afforded any room to breathe, shown here in a dark, cinematic space, and the symbolic imagery of the anonymous rider against the barren desert, with all its moodiness, anonymity and latent threat, is a promising start, even with the obvious parallels being drawn to Sidney Nolan’s iconic Ned Kelly series, which naturally appears later.

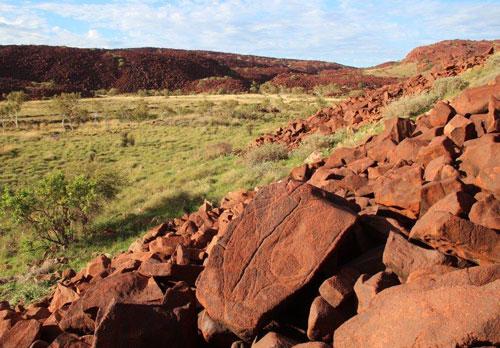

The next space (it’s a linear journey room to room) is dedicated to the work of significant 21st century Indigenous artists including Emily Kngwarreye, Rover Thomas, Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri, Doreen Reid Nakamarra and Sally Gabori. It’s a confident next step curatorially from the opening Gladwell, with the cast of abstract swirls, undulating zigzags and confident colour palettes of these truly beautiful works positioning landscape as a sacred, visual language and a necessarily abstract one at that. But it’s downhill from here.

Two enormous rooms are then given over to the work of early colonial artists, including Conrad Martens and John Glover. Despite the name-checking, it’s a veritable feast of limp landscapes in muted, watery shades of green and brown that illuminates little beyond the struggle of these early artists to pit their romantic European visual vocabulary – think Constable and Turner – against the abject and exoticness world of colonial Australia. As a moment of social and art history that struggle could be interesting to explore, but it’s so firmly presented as a collection of landscapes (where Aboriginal people are captured as murky, malevolent shadows) that it’s just profoundly dull.

From here the show moves swiftly to Australian Impressionism, where the country’s dazzling light and heat is for the first time deftly captured by Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton, et al. Despite the dogged chronology, there is certainly pause here to appreciate the effort in bringing together such iconic works. From Roberts’ A Break Away! to Streeton’s “Fire’s on” (Lapstone Tunnel), these are vivid, extraordinary paeans to a new understanding of Australia as something finally, absolutely, distinct from Europe.

There are darker, more ambiguous works on display as you shuffle through to early and late modernism. Paintings by Albert Tucker, John Brack, Russell Drysdale, and of course Nolan, depict landscapes that resonate with broader social tensions and anxieties. But again, with no space to contemplate each work, it’s impossible to make any of your own intellectual or emotional connections. It becomes almost laughable when Max Dupain’s iconic Sunbathers (one of the few photographs to appear in the exhibition before you get to “Contemporary Australia”) is found wedged into a corner next to Charles Meere’s equally iconic Australian Beach Pattern (1940). “The Beach” is represented in one corner – “Sydney Harbour Bridge” in another, with a triptych of works by Harold Cazneaux, Grace Cossington-Smith and Jessie Traill respectively. These heavy-handed literal groupings only serve to make clichés of the work and it is a tremendous shame.

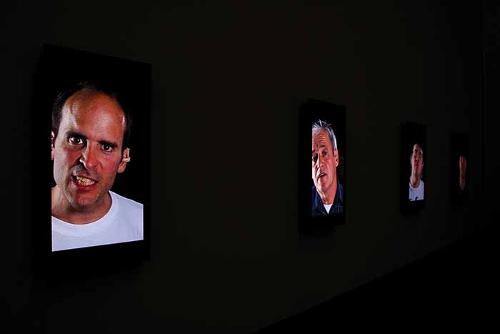

It is only in the last two last rooms that the landscape starts to get necessarily ambiguous and determinedly complicated. From Hossein Valamanesh’s aching meditation on migration and ritual in Longing/Belonging (1997) to Gordon Bennett’s excoriating Possession Island (1991) and Danie Mellor’s An Elysian City (of Picturesque Landscapes & Memory) (2010), these contemporary offerings understand landscape as a connection of social, historical, political and cultural constructs. It’s a much richer viewing experience, although again it is frustrating that whole series of works, such as Vernon Ah Kee’s Can’t Chant (2009), are reduced to a single photographic frame for the sake of including other works such as Kathy Temin’s dreadful felt memorials.

A more ascetic, thematic approach would have better served both the artists and the exhibition and it does leave you to wonder about the politics of this joint Royal Academy/National Gallery of Australia effort. There are genuine glimpses of having something interesting to say, however accidental they feel, and it is curious to explore the exhibition as an Australian in London, wondering who this “Australia” is for and which “Australia” it is trying to represent.

The relationship between the UK and Australia is naturally historically complicated and undercurrents of this dynamic still exists today, even if it’s only best articulated on the cricket pitch. The problem with creating a traditional, historical survey show about Australia’s landscape, where landscape mostly means trees, is that it simply serves to reinforce age-old stereotypes not only about Australia, but our relationship to Europe as well.

The inclusion of Indigenous art is an attempt to redress this perhaps and to present Australia as its own complex place, but this could have been done more rigorously and critically. Without the space and subtlety that a more confident curatorial approach might afford, this exhibition sadly does nothing to update or complicate any of the visual clichés that dogged Australia, nor offer any new insights and as a result it’s a frustrating experience.