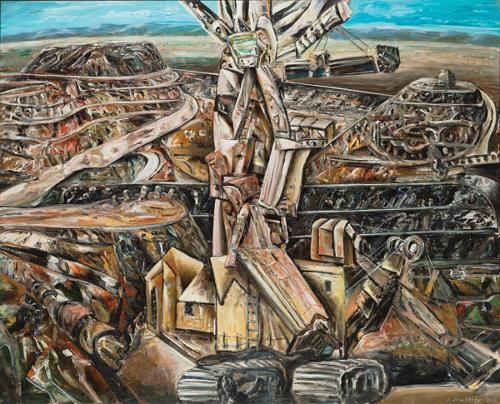

Since time immemorial, that which lies beneath the earth has been culturally associated with chthonic forces—the promise of abundance and the terrors of the grave. But our knowledge of the science of the earth’s crust and its molten core have exploded the idea of a mysterious underground realm; here in Australia images of the open no-holds-barred expanses of the Kalgoorlie Super Pit suggest that old deities of the underworld have nowhere left to hide.

Nevertheless, art and the underground have enjoyed a long and deep relationship: subterranean galleries were the sites for the first images known to Europeans in the caves of Altamira and Lascaux, where the mystery and power of the underground spaces helped create the magic of art. The subject of that which lies beneath the surface of the earth has spawned a wealth of responses and there is a sense in which the subject of mining could be seen as another iteration of the age-old involvement of art with issues to do with the underworld.

Images abound: Virgil’s Aeneid and Dante’s Inferno located the subterranean world as the territory of damnation—one that had to be dealt with through a process of emotional and moral mining. More recently, Sebastiao Salgado’s unforgettable images of the Serra Palada goldmine in Brazil (1986), where men crawl like ants, gouging at the earth’s surface with their bare hands to reach the promise of wealth, reinforce the at-times primal responses to the wealth beneath the earth. Gold rushes are described by Pliny the Elder, and the deep earth’s promise of instant wealth has fostered outbursts of feverish energy that ignite passions of all kinds.

Here in Australia the most recent promise of mineral wealth has ignited fiery debate and polarised opinion. This particular grappling to understand our relationship with the subterranean has come with a new awareness of issues at stake, with knowledge of the environmental impacts of mining weighing in with high chips. No doubt this phase of our changing relationship with land in this country will spawn new ways of visual representation.

Much has been written about the failure of the European landscape tradition to adequately deal with capturing the sense or experience of the land in Australia. One image made in 1843 a small watercolour by explorer-artist EC Frome (1802–1890)—depicts the artist confronting a vast, limitless nothingness. He is mounted on horseback, at one remove from the land, as he trains his telescope on the measureless flat plains of emptiness before him, a tiny figure suspended beneath a pale impassive sky and the line of his vision intersects perfectly with the horizon-line. It is as if he himself has become the instrument for gauging the meeting place between nothing and nothing.

The little picture evidences the almost insurmountable difficulty of apprehending so much of the Australian landscape from a European perspective. From this vantage point, so much of this ancient country resists offering up the details of foreground, mid-ground and background through which European vision established the sense of the sublime in nature. Yet explorers’ and artist-explorers’ notebooks are scattered with references of their awareness of an elusive sublime. And because the land would not conform to the genres and codes of the European landscape representation, artists were challenged to find other ways of representing the land.

At the turn of the twentieth century three iconic Australian landscape paintings shake off this perspective by tilting the landscape’s horizontality into a vertical axis. In three works—Arthur Streeton’s Fire’s On (1891), Tom Roberts’ A Break Away! (1891) and Bailed Up (1895)—the land is presented to us 'face on’, and by way of this radical shift in perspective the land becomes something other than a setting or context. Rather, it seems to take on the role of another kind of character: In A Break Away! it is as if the lie of the land is responsible for the ensuing chaos; in Bailed Up the flat screen of apparently impassive terrain seems complicit in the crime it witnesses. In this issue Daniel Thomas describes Streeton’s representation in Fire’s On as if “the land itself has become a violent animist force, suddenly malign and murderous.”

The representation of the Australian land as a force that one comes up against as a kind of presence, a face-on protagonist, emerges. It’s there in Drysdale’s The Rabbiters (1947); it’s there in Nolan’s Central Australian paintings and Wimmera works, and the country literally becomes the face in Albert Tucker’s Antipodean Head series. It has been tilted into the flat forever “field” of Fred Williams’ work, and before all this it is the axis of presence in Indigenous representations of country.

If representation of land can be read as the metaphorical representation of the body of the nation in Australia, then how to visually represent these gougings, re-shapings and woundings made by mining in order to re-imagine the consequences of the relationship with the land that we have established? In this issue Michael Taussig describes the possibility of art functioning as a kind of "apotropaic magic" — images or rituals used to ward off impending evil. He shifts the surface anxieties of the mining debate deeper still into an argument that traces back to the effects on the stromatolites — the earliest known fossils found in the Precambrian rocks of the geologically oldest continent on the planet, and asks us to imagine the links that relate us to age-old life-forces that we are still to fully comprehend.

On the surface of things the “mining debate” may chunter on about profits and loss and dividing the spoils. Evidence of the ecological impact magnifies the urgency of the current situation but the chthonic forces that have been linked to such subterranean subjects take this debate deeper down and into our psychic relationship to the earth.