I will begin negatively, but kindly persist, dear reader, because I will end with a flourish of positives.

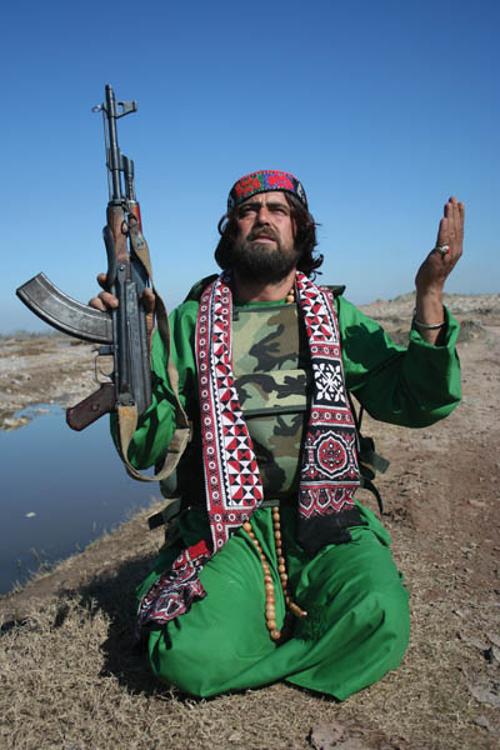

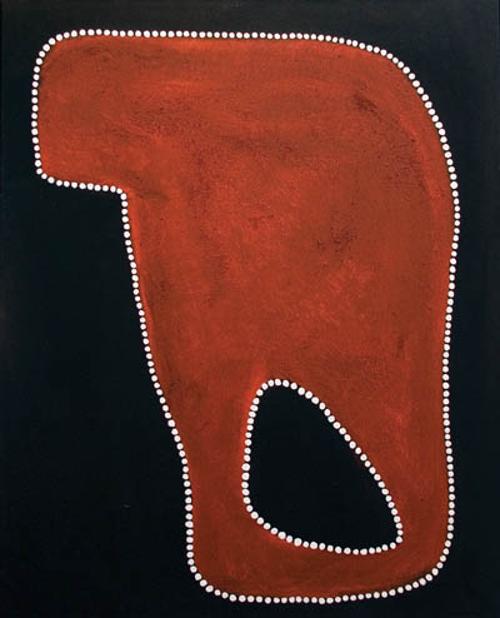

The negative is a truism: there are too many people in the world, and too many of us are producing too many things. This is the situation the mature Jon Cattapan has been addressing for many years now, recognising that many of us live virtually in a trans-national mega-city - and that others are in places so troubled by the real consequences of clashing cultures and the ruthless blunderings of empire, that they are driven to the untender mercies of people smugglers and the border barriers politicians erect against them. Yet the artist is no preacher. His work stems, rather, from the fertile seed-bed of Melbournian expressionism and surrealism. He balances recognition of global injustice - and, on occasion, tabloid drama – with intuitions about the underbelly of our psyches, our evolutionary inheritance of a feel for beauty, our predilection for dark mystery. This layering means that Cattapan moves well beyond formulae, formalism or cheap effect, into the zone - at age fifty-two - of Australia's artistic elite.

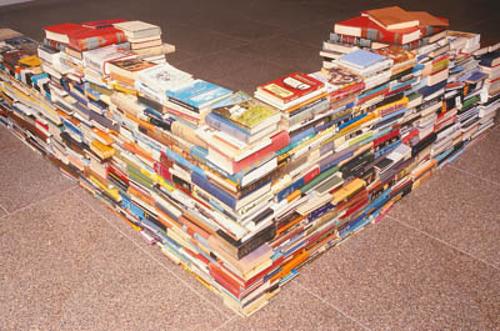

Pop and punk also came into play in Cattapan's work from the 1970s, based around life in St. Kilda, a touchstone to this day. His early work was unfashionably if presciently figurative, his first solo show (at Realities Gallery in 1983) a mixed success. Travel overseas, especially a stint in New York from 1989-91, established for him the far pole of the 'glocal', to employ that useful albeit infelicitous neologism for the local and the global perceived as a seamless whole. The artist's observations of popular culture reinforced this perspective, as did his reading, including J. G. Ballard and Fredric Jameson. The stars aligned to allow Cattapan's signature cityscapes, including 'The City Submerged' cycle from 1991, 'The Bookbuilder', 1992, and a host of other works.

Cattapan's work at this stage seemed to epitomise Jameson's seminal essay, 'Postmodernism, or the cultural logic of late capitalism' (1984), which ventured 'cognitive mapping' as a way of gaining control in a drowned world of dissolving referents. The artist's sparkling grids of skyscraper lights and the emanations of traffic flows against intensities of Turneresque colour doubled as electronic vectors across evocations of more abject, sexual and complicit forms of life. The works sometimes physically comprised multiple canvases of varying sizes and shapes, with imagery compiled in a computer yet offered through the slow sensuality of paint. Figures have come to the fore again in latter years, agents and victims of social change. Limned initially in protest at reactionary politics of the Kennett and Howard governments, they continue to appear as signifiers of threatened communities.

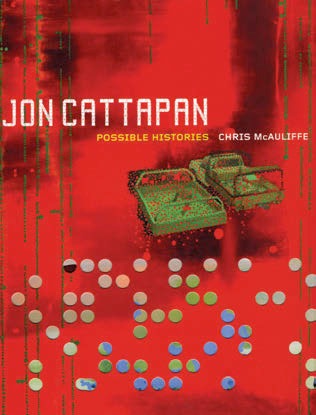

All of this is expertly chronicled by Chris McCauliffe, who is among the most incisively insightful of our art commentators, whether via radio or writing. He seems comfortably across the theoretical and art historical frameworks pertinent to Cattapan's career, wearing his knowledge lightly but effectively, without laboured agendas. No warmed-over thesis this. Most of the material one reads, or begins to read, about art is boring. Again, not this book. It benefits from a long (twenty year) and respectful relationship between the artist and writer. If the artist's voice comes through strongly, it is within a framework of non-hagiographic understanding, and the book's integrity does not feel impugned by the apparent closeness of author and subject.

A consultative connection between the artist and the book's designer, Hamish Freeman, has also borne fruit. The resultant publication manifests something of the feel of an artist's book or of a 'culture magazine', with frequent runs or riffs of illustration evincing an almost web-like interactivity with the artist's aesthetic. The book is comprehensively illustrated, and if the pictures are not cross-referenced in the text, they are usually easy to locate without recourse to an index of artworks (a more comprehensive general index, incidentally, would have advantaged the book). In spite of the uncertainties which Cattapan evokes, his vision does not seem dystopian so much as a rich, even ecstatic, celebration of life, whatever its gritty, city frame or subterranean mysteries. This perspective is embodied, not merely illustrated or described, in this publication.

So now to a trio of climactic bouquets. This book should be purchased and read because it is about a major artist, is penned by an important writer, and is an exciting artefact in its own right.