A curiously traditional set of painting skills and methods are employed by Megan Walch in the service of some utterly contemporary concerns in Doppel Lecker her first solo exhibition in Hobart since Shocking Crashes and Chases at CAST in 2000.

Since that time the focus in her work has pared down to a defining essence of our times – objects of desire and their promises of gratification. These paintings are all about surface, the luxurious skin of the new. We are all to an extent complicit in the desirability and sensuality of the new object, the smell of a new car, the unblemished polished surface of a new appliance and the ultimate skin of mechanical perfectitude, chrome.

Yet there is a denouement at the heart of this transaction, the surface will never be better, the gloss will fade, living with objects scars and etches stories on their once pristine faces. Entropy gets to work at the point of conception and death enters once the deal is struck. The engagement is fated from the outset, the desired dies from the very loving of it.

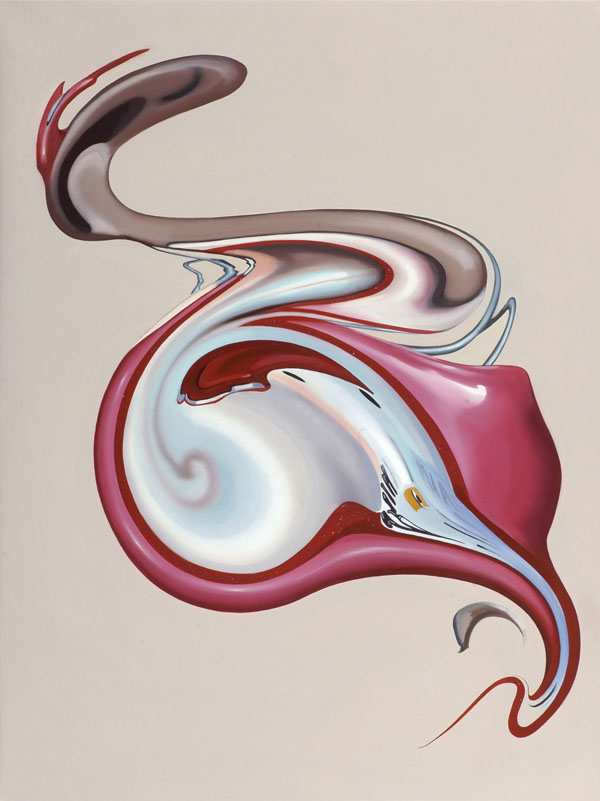

Yet the chrome surfaces depicted in Walch's distorted, abstracted selections from the object world refer beyond the slick obsession with surface. As Walch so skillfully depicts it, chrome is actually not a presence but the reflection of everything but itself. Thus it may suggest the ultimate immateriality and insubstantiality of the 'desired' at the same time as it reflects the material world we seek to leave for the embrace of its promise. This dichotomy is central to the nature of desire.

The forms from which these surfaces derive have been transformed into fluid shapes which manifest as a series of blobbed, fluid forms, caught for a moment before they slide off the canvas altogether, dribbling and mutating constantly, ungraspable and unfixable. The world is held momentarily in a reflection, the non-materiality of the mirror implicitly extended into the non-permanence of the transient flow of things.

As with any reflection, the engagement with these paintings slips between the two dimensional face of the forms and the interior world of the reflection itself, the physical world floating in the chromium bubble receded and advances, existing at the liminal point of becoming more or less abstracted but always hovering on the cusp of both. This is particularly true of the smaller paintings in which the object sits centrally, few clues to its derivation are present, it has mutated into a thing without apparent parentage, a curious, anomalous yet insistent presence.

In larger compositions such as Banglampu the Vespa scooter which spawned it still lives in the wildly distorted body of its former state, at the point of total dissolve into unrecognisability and the life of lost mutants. Doppel Lecker 3 (Faraday Street), describes in its title the dual life of these images, the petrol tank of the scooter reflecting and apparently containing the world outside it.

The experience is not unlike stumbling across a melted-down world of objects in which colourful, shiny blobs suddenly reveal an unmelted part which signifies the whole life of the previous conformation of atoms and molecules, the last link to another life about to be absorbed, atomised and abstracted out of utility and out of meaning. The suggestion of an atomic world in constant flux is inevitable. You are reminded that entropy is not in fact destruction but re-configuration, that all arrangements are contingent, that any locking down of molecules into the figments of human imagination is always chafed against by nature.

These metaphorical allusions may be those of the viewer as much as of the artist but the metaphor is inescapable and by inference carries further than a relationship with objects or consumption. It goes to the heart of the world which we make. Most First World human time is spent inside the synthesised realisations of many, often-linked imaginings like film and cyberspace. Desire and imagination are tied as need and imagination, but the nature of the Western (and more latterly, Eastern) world is to enculturate the physical world into visions made material, into desires realised. We live within this imagined world of spaces and objects, we add to it, and often the only way we encounter the 'natural' is when it is accidently reflected in the surface of one of those creations, or through the lens of yet another.

That this is all contingent, all ephemeral, all conceit, is the deeper lesson of this work and the value of its statement here and now. The real strength of this show is that the artist, through consummate technique, has seduced us into an engagement that we might remain long enough to allow that awareness to enter.