The recent past is more elusive and more frequently elided than the established histories of a distant past. Serendipitously, Melbourne's CBD over July-June 2000 saw two exhibitions that explored different aspects of the visual experience of the day before yesterday. RMIT's hosting of a touring exhibition Fluxus in Germany 1962-1994: A Long Story With Many Knots brought major artists of the 1960s and 1970s such as Joseph Beuys, John Cage, Hening Christiansen, Nam June Paik into the city as representatives of high avant garde culture. Five minutes walk away at the Outre Gallery the immediate, invisible past bubbled to the surface in a very different manner in Little Rippers: Australian Fringe Pop. Works from twenty artists were not linked by cohesive formalist bloodlines, but ranged from graphic illustration, careful draughtsmanship to constructions of found objects and montages of scavenged printed material, straight out of the dada tradition that begot Fluxus; however the spunky, genial, self confidence was free of the high cultural seriousness of Fluxus. Artist Gemma Jones, curator of the show, had just completed a Masters Thesis on "Nostalgia in Contemporary Australian Art" and her selection provided an entirely plausible exposition of a phenomenon, currently widespread, but not greatly documented: the quoting of the colours, shapes, surfaces and motifs of the lower, tackier, mass-produced levels of mid century modernism by (mostly younger) artists. Like all satisfying curated exhibitions, Little Rippers produced that "but of course ..." revelation in the curator's identification of cultural patterns and the persuasive guiding of the viewing to read and see the theme.

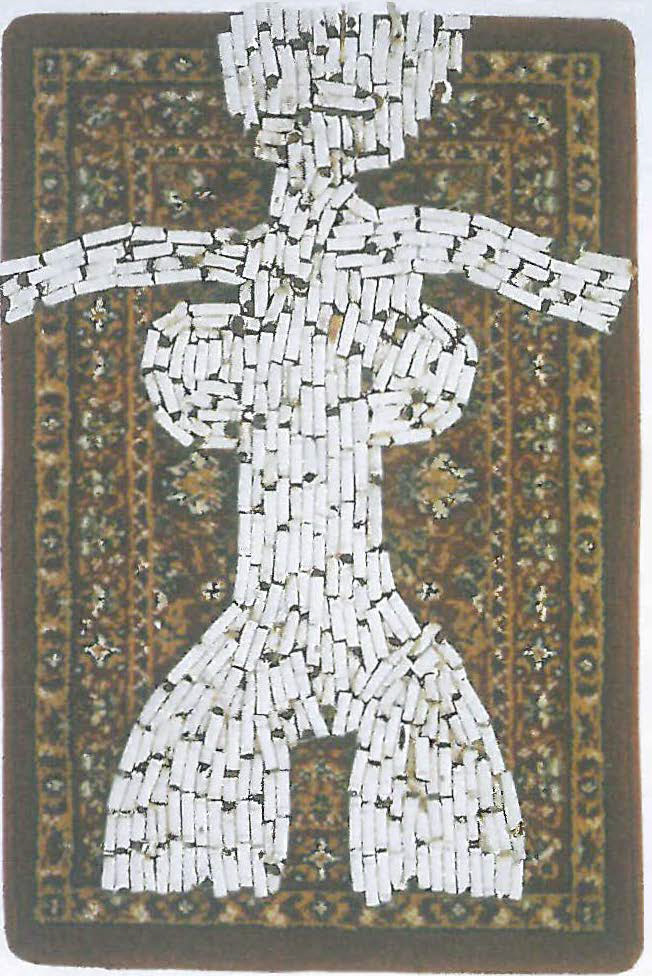

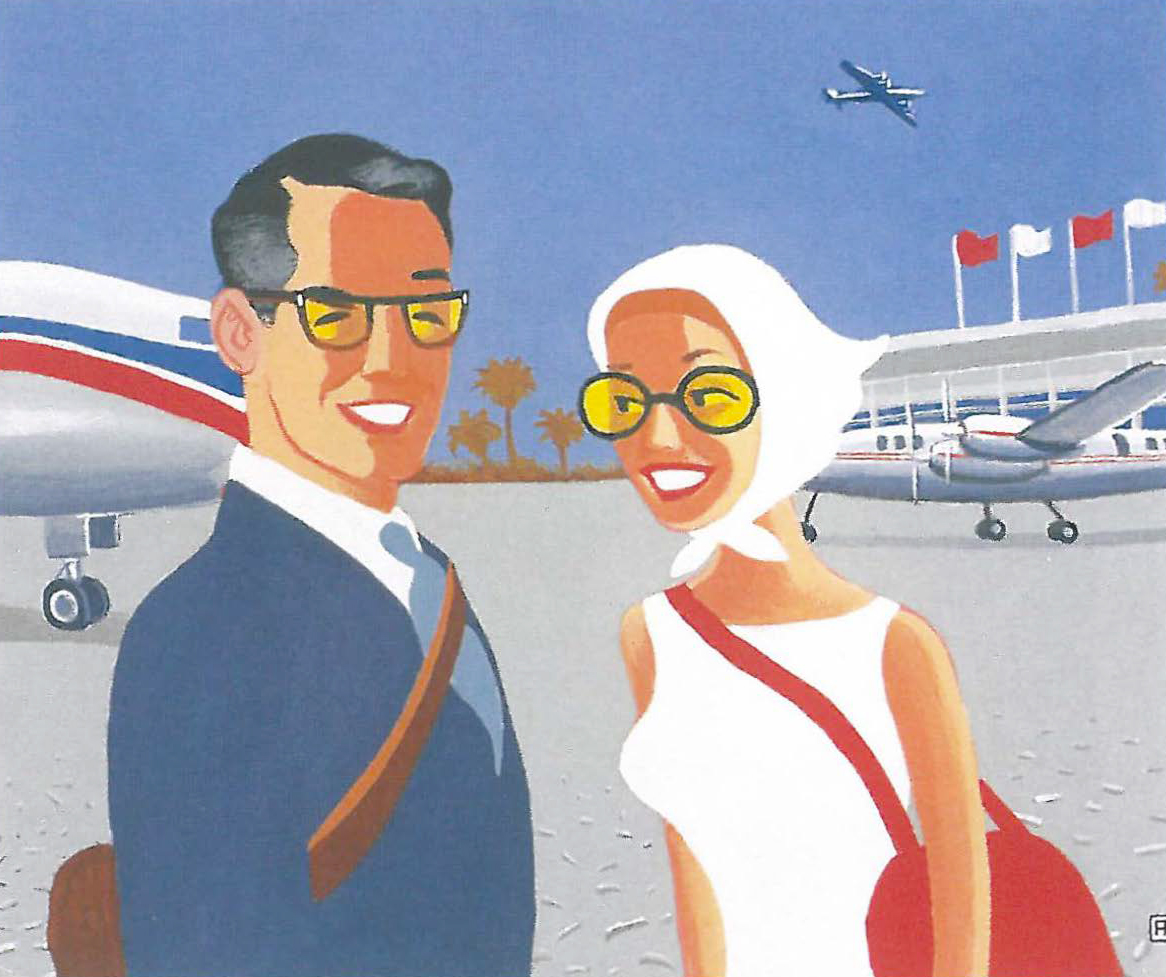

The curatorial brief "Australian Fringe Pop Art" led to artists with established profiles such as Geoff Raglus of Mambo, or Perks whose 'interventionalist', non-sanctioned public art is well known in Melbourne and on the other hand to less authorised illustrative and representational styles, including Jo Mihalov's feminist celebration of calendar art and Betty Page, to Jeremy Geddes and Nick Arnold's' referencing of a non-mainstream surrealist baroque genre of figuration that has found adherents for more than two decades. Pin-ups, comic books, Vargas, Warhol, advertisements, television, B-grade film, big-eyed child prints of the 1960s, dress patterns, interior design, wrestling, tattoos all found a place in a lingua franca shared between artists and audience. Many of the artists had links to the music industry as well. The catalogue openly attested to the exhibitors' involvement with mass-produced visual ephemera and commercial art, as much as formal training and mentorship. Thus Jo Mihalov's collection of "Vintage Americana" illustrations and Neryl Walker's dedicated op-shop scavenging publicly inform their art and give authority to their voices. Nostalgia is referenced through the imbrication of pleasure and brand-name recognition.

.jpg)

The young and pop by no means came off badly in comparison to the fading and tendentious Fluxus, rebels of the day before yesterday, granted that I find myself frequently on the side of low rather than high culture. Joyfully the artists in Little Rippers presented makers and viewers as equally consumers and subverters in a capitalist continuum. Conversely the signage indicated that many of the artists in the Fluxus exhibition had enjoyed long, officially-sponsored careers, facilitated through residencies, exchanges and travel grants, even when their stated aim was disruption of establishment culture. Little Rippers celebrated the popular and everyday, the vernacular wallpaper of capitalism and the commonplace life that the Fluxus group sought to challenge. thus pointing up limits and blind spots in the voluble Fluxus rhetoric. The dialogue between the shows also prompted consideration of that great conundrum of modern art - as pointed out eight years ago in Artlink. "Why should the bitten hand of the cultural patron so generously come back to feed the rabid dog?"[1]. What is in it for the patrons, quite a deal if it shows them as hip, broadminded and left of centre.

Yet is the dog rabid, as much as an overstuffed, slothful pedigree show Pekinese on a velvet cushion. Certainly the Fluxus show marked a crucial moment in the history of conceptual art which demands attention in the light of the continuing vitality of installation and conceptual art in Australia. Relatively few shows/surveys of European art that deal with the post-1945 past reach Australia and such initiative should be commended. The installation, which made a more than usually effective use of the RMIT gallery was backed up with ancillary events, including musical performances to underline the historical significance. Yet in some ways the negative issues are even more interesting than the many pluses (the latter I shall unfairly elide due to lack of space). Despite the undoubted historic moment of Fluxus, so many of the questions and insults seem now tame, when for a number of decades artists have been bringing all manner of objects into galleries, dissecting and rearranging them. Visually the most compelling elements were the tell-tale signs of aging that imposed a de facto mortality on the high rhetoric. The cool austerity of sixties taste, when not unashamedly trailer park and laundromat like Little Rippers' mass market reiterations of modernism, becomes its own undoing. Authority and cultural power ebbs in a sweetly melancholic fashion through the yellowing of thin papers, the fading of pencil lines, the darkening of blonde varnished wood fixtures. That former Bauhaus clarity - which recalls the interior fit-outs of so many Australian University buildings of the 1960s - now in its diminishment suggests a melancholy moment of the exposure and whittling down of privilege.

In avoiding state-facilitated modernism's monolithic enlightenment rhetoric to voice the abject and overlooked in a friendly dialogue with the viewers, Little Rippers contemplated the true poetics of the everyday and examined a recent past that was both fun and more wilfully, perversely off-centre than "relaxed and comfortable".

Footnotes

- ^ Artlink V12 no 1 1992 p 73