In response to the questionnaire sent out by curator Malcom Bywaters to the artists of Boogie, Jive and Bop, Stephen Haley replied, 'Artists don't answer questions, they pose them.' Rightly so. Art should get the viewer thinking in a way that pesters the sluggish brain into heated inquiry. The works included in Boogie, Jive and Bop were a stimulating mix, however, the curatorial concepts (and the title) pestered me with more nagging questions than the artwork did.

Described as 'a survey exhibition' featuring the work of twelve contemporary artists (the Hobart show featured only eleven), Boogie, Jive and Bop was set out to be a selective response to the creative energy generated by events taking place after September 11th. The war on Iraq, the SARS outbreak and the Australian government's refugee policy were all topics of questions answered by the artists and printed in the catalogue text. For me, the wandering focus of the questions was confusing. I found it difficult to find a connection between Bywaters' heavy-handed political inquiries and his probing of 'coffee shop rituals' and 'favourite restaurants.'

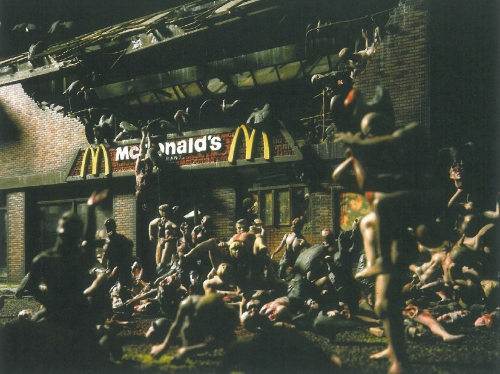

Standing strong on the strength of the work alone, Boogie, Jive and Bop was one of the best collections of contemporary art seen in Tasmania this year. Given the title, I was expecting a frothy selection of laboriously academic pop art. On walking in to the exhibition, this thought was immediately (and thankfully) dashed. The dull, strangulated hum emanating from Shaun Wilson's My Sweet Mnemonic Wonderland, made the air of the gallery thick with a deep sense of foreboding. Sudden inflections of a shrill telephone ring punctuated the air at random intervals and kept me on edge. Wilson's video soundtrack was the perfect backdrop for the sinister undertones of several other works on show.

Michael Doolan's unmistakable Friend of the Family stood out in its bright canary yellow and unashamed nostalgia for the playthings of childhood. A master at combining warm fuzzy feelings with a bitter tinge of malevolence, Doolan's Friend of the Family made for a zesty centrepiece. Looming in front of a tight gaggle of roly-poly dolls of varying sizes was a waist high, blindfolded toy bunny. Wielding a thumbtack-like weapon in its right paw, Doolan's bloated Miffy exuded a threatening malice lurking beneath its podgy, seamed exterior. Whether potential victims, a reluctant army or stalkers themselves, (how far can a bunny go with a blindfold on?) the dolls stood motionless, ready to roll into action at the drop of a thumbtack.

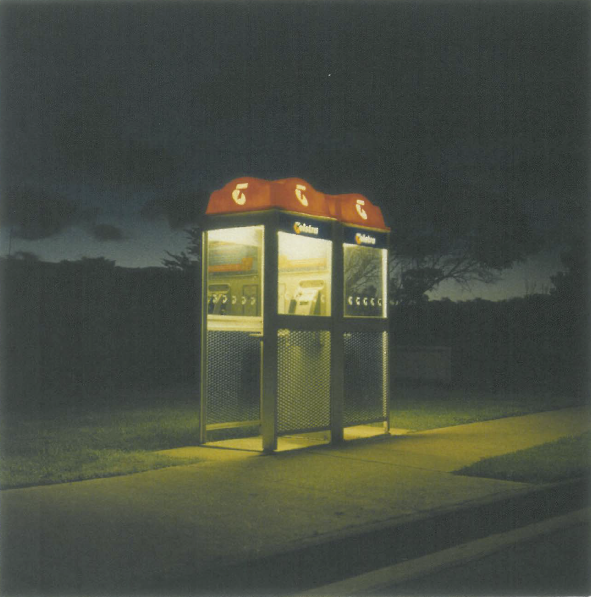

Jane Burton's The Other Side retained the still, cinematic suspense of earlier works while using the metallic structures of phone booths instead of anxious female bodies. The empty booths appeared as gleaming beacons within a seemingly desolate landscape of dimly lit hotels and sidewalks. Burton captured that gut-turning feeling of waiting for something to happen. Will the phone ring? Who will emerge from the darkness to answer it and what will they say?

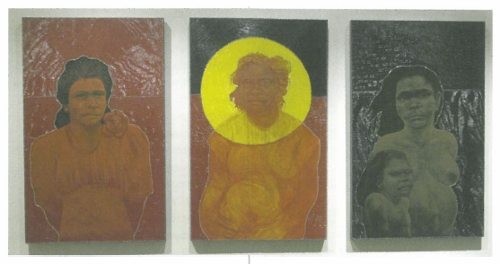

Themes exploring the natural and the artificial were evident in most of the works in Boogie, Jive and Bop. Robert Bridgewater's sublime wooden vessels echoed the sacred flora of a distant civilisation.

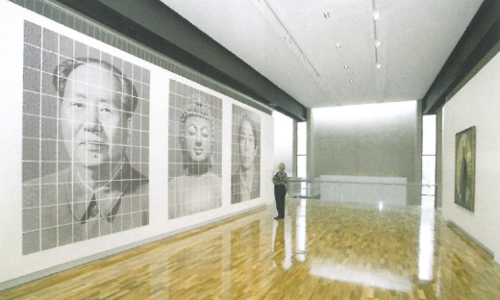

Hundreds of paper cuts reminiscent of the pressed flowers one might find in between the pages of an antique book made up Kate Cotching's A Place for a Village. Cotching's work hovered above the floor, spread out over wire netting like topographical layering; a delicate contrast to Stone Lee's quirky plastic trucks and carts sprouting newspaper covered kitchen Tupperware. At the other end of the gallery, recent work by Danielle Thompson and Troy Innocent referenced the superficial surface of film and popular culture through the medium of the lightjet print.

In a striking twist of voyeurism, Penelope Davis placed the camera under interrogation in her x-ray like images of Polaroid cameras, while the painterly portrait of Philip, by the masterful John Derrick, cast a distracted eye into the unknowable space suspended between the viewer and the intimacy of the studio.

Survey shows are notoriously difficult to curate and given their broad range, a simple theme often works best. Publicised as an upbeat collection of work, in reality, Boogie, Jive and Bop was a distinctly unnerving experience. Without the curatorial meanderings, Bywaters' apt selection of work was enough to make me want to see more art of this calibre grace Tasmania's southern shores.