Buying things is a regulated exchange. But finding things and putting them somewhere else is a simple, enjoyable activity that most of us engage in; moving house or rearranging the furniture. It enables us to look at things anew, to reinvest in them. Like a form of gambling, the lucky find can imbue objects with magical significance. Many artists employ this ecological beach combing, reminding us that the provenance of art-works is more anonymous and social than just a pure act of will or creation.

Rather than yet another take on the readymade object, Group Material, in the Queen's Warehouse Gallery at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, contains work that points to the possibility of something else going on. Recontextualising the utilitarian object is one thing but what an artist does with it, at the same time, is another. The found object could then extend to the structure of its making, as a found process.

The artist has abdicated a specialist technical profession. Specific technical demands and quality controls for art are now so relative that artwork has become removed from standards that would otherwise govern them in a market driven economy. Many artists nowadays borrow know-how from other professions whilst still identifying themselves as artists. They have become technical dilettantes or applied conceptualists, enabling them to address broader social issues about the regulation of our time and labour and where the artist fits into this.

Whilst referring to the specifics of pure Modernist abstraction, Neil Haddon's paintings Patch Nos 1& 3, are at every turn a compromise of those ideals. The colours he uses are determined by the hardware stores' fashion range for home interiors, thus aligning painting with painting and decorating. He furthers his apostasy by painstakingly rendering the wear and erasure of time and accident on their pristine surfaces. Anthony Johnson bolts Type C prints on aluminium to flimsy cheap handyman objects of conveyance such as ladders, shelves, or trolleys, in his Utilities. The weightless images of the transitional spaces of industrial development refer to the weighty issues of the social impact of such development, usually kept out of sight, out of mind. The heavy bolts used to suspend these images onto the supporting objects prompt a variety of puns. Johnson's interest in DIY culture suggests the problem of balancing almost insurmountable ecological degradation with a pathetic attempt to neutralise or mask their reality. Home renovation programs have become a rash-like symptom of social anxiety that try to fool us into thinking we can get away with spending as little time and attention to detail as possible and still be in control; that it would be unviable to do otherwise.

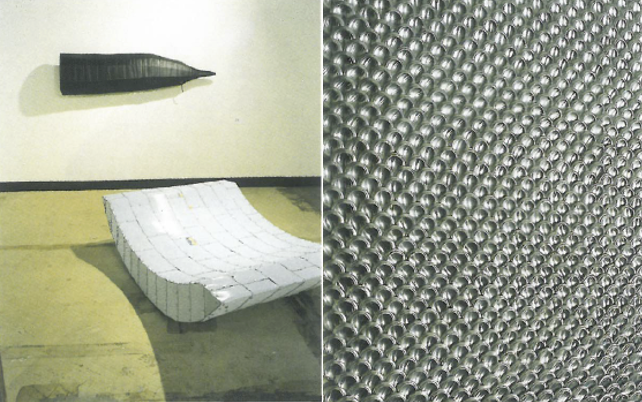

Lucia Usmiani's Something fishy, is a spectacular recycling feat, where the mundane addition of identical units – in this case the bottoms of tin drink cans – becomes far more than the sum of its parts. Ben Booth applies a similar technique of attaching units of a carefully selected material together, to form an almost magical transformation, while maintaining the integrity of that material, in Pressure and Unit. Both these artists achieve such outcomes by ingenious improvisational technical means. The repetitious mechanical process appears to be born from the units themselves, as if the outcome was inevitable. I do therefore I am, sums up the philosophy of these artists' activities even if they haven't a specific name or Job Description.

This kind of technical improvisation has links to the model of unconditional labour that the character Robinson Crusoe symbolised in Daniel Defoe's famous novel. Often criticised as being the archetypal individualist, Robinson Crusoe toils only for his own benefit and is therefore trapped on his island of solipsism; living, feeling and dying in isolation. But the irony of individualism is that it's a social invention (like Robinson Crusoe himself) and that perhaps what saves him from madness is that he is unable to conceive of an invisible death, death being a concept for the living. He's not just himself. He produces for himself but he can't help but be a social creature. The found objects (primarily from the shipwreck) and the found techniques he utilises, learned from the country he was alienated from, allow for a glimpse at a radical reappraisal of labour itself outside the viability of market values and the self-righteous redemption of a work ethic.