In his book titled What Painting Is, James Elkins ties the processes of making visual art to the ancient methodologies of alchemy. Elkins' primary focus falls on painting, and on oil painting in particular. Although the book is fascinating in parts, the author's attempts to tie the two pursuits so tightly together often lead to some strained and at times counterproductive connections. Like at the end, where the author claims that:

'Science has closed off almost every unsystematic encounter with the world. Alchemy and painting are two of the last remaining paths into the deliriously beautiful world of unnamed substances. (p. 199, Elkins, James, 1999, What Painting Is, Routledge, New York)'

Somewhat perfunctory, if not downright laughably limiting. Not only because, given the ruin and discredit that alchemy has fallen into, Elkins' defence of the rather narrow field of painting doesn't seem to be offering it too rosy a future; but also because Elkins seems oblivious to the myriad other ways in which materials can be transmogrified by an artist's attention.

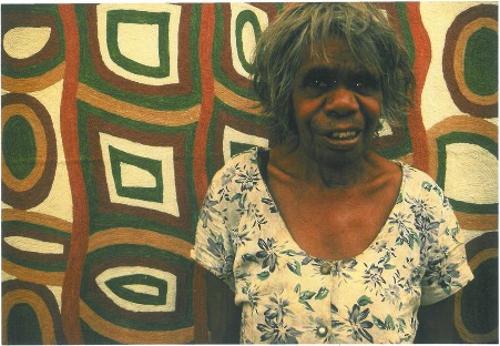

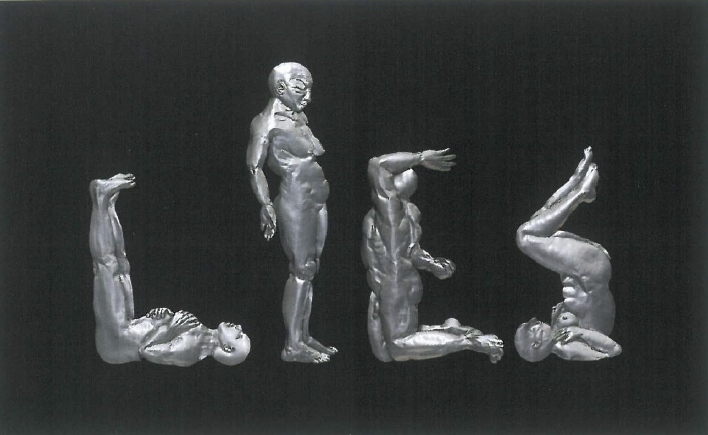

Fiona Hall's current exhibition at the Queensland Art Gallery offers such myriad examples of approaches to art making where ordinary substances are transformed into extraordinary new presences. Trained as a painter, she has embarked on a career where her curiosity about and delight in the cornucopia of materials available to contemporary visual artists continues unabated.

There can be little question that a great deal of the immediate appeal of Hall's work lies in the ways in which she takes the ordinariness of everyday materials and transforms them. In some works their original nature is evident at first glance, such as the bank notes used in the Leaf Litter (1993 – 2003). In these the fineness and intricacy of the paper money from a range of countries are interwoven and overlaid with delicately painted gouache images of botanical specimens.

In other works, however, the original nature of the media is less immediately obvious. Tender (2005-05), for example, also uses bank notes, but their transformed, shredded re-presentation makes their monetary value not so immediately apparent. The tender and lovingly constructed nature of these works provides fascination enough. However, the longer look's realisation that the avian homes have been constructed by thinly sliced American one dollar bills moves the purely sensual level of the work into the deeper, cheekier and slightly more sinister level in which Hall is so adept.

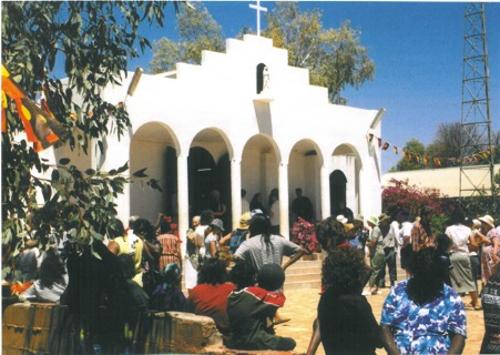

This current exhibition at the Queensland Art Gallery coincides with the publication of a lavish book by Julie Ewington, who is currently Head of Australian Art there. Both the exhibition and the publication examine Hall's work over the course of the last thirty years, and both moderate the diversity of forms, materials and ideas of Hall's prodigious output through an elegance of greyed, restrained presentation.

Yet the riotousness, playfulness and often sheer eccentricity of Hall's work cannot be contained by any such muted restraint. The works survive explanation to seduce and fascinate, and, judging by the responses of visitors to the show, continue to pose questions and conundrums.

Ewington has structured the main body of the text into five sections. These are offered as a framework for understanding Hall's work that wisely sidesteps the more obvious approach of dividing the survey up according to media. In Seeing Meaning, Making Meaning, for example, Ewington describes how Hall's development of major themes during the early years of her development was instrumental in moving her work from an approach of perceiving the connections inherent in the relationships between things to the act of constructing relationships between things, materials and contexts.

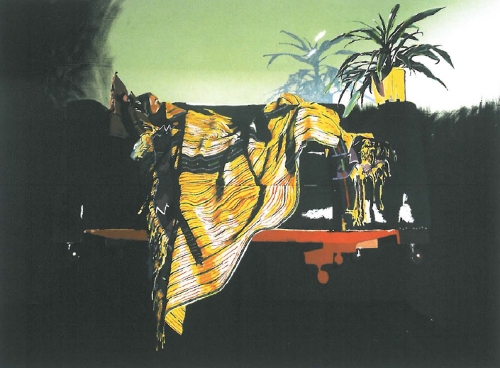

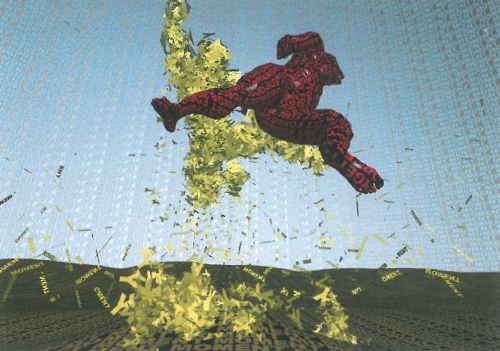

In the second section, Chaos, Knowledge and Order, the author examines that knife-edge between incoherence and articulacy that Hall seems drawn to. The abundance, opulence and restless patterning that often threaten to engulf the clarity of the images and ideas are only just won back time and time again by the artist's formidable intelligence. Here Ewington uses Hall's themes of purgatory, hell and despair to describe a passage of darkness and questioning in the artist's work that now, the writer suggests, seems to have passed. She concludes this section with the statement:

'Fiona Hall's travels on the dark side were over.' (p. 96, cat.)

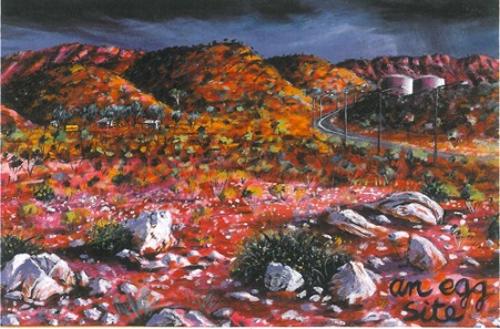

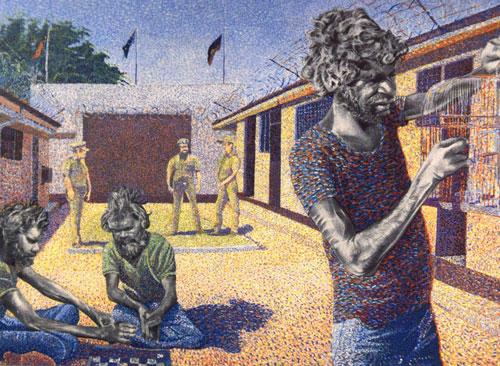

The following section, titled Sex and Gardening, takes a more light-hearted approach to the named perennial themes in the artist's oeuvre, with close attention to the rich repertoire of materials and ideas the artist has dealt with. And Contemporary Vernaculars and Serendipitous Intersections are used as a framework by the author to explore interrelationships of life and death, beauty and violence.

Throughout the book Ewington's passion for art making in general and for this artist's work in particular does nothing to short-circuit her commitment to objectivity. She is a keen observer, a meticulous scholar, and a critic who is not afraid to state when she believes work has been less than successful. In passages her writing also approaches the poetic. In her conclusion she writes,

'The work itself is sometimes the first effect of these spells: the words come, as if unbidden, and the artist transforms them into substance. (p. 179, cat)'

The publication describes this artist's dalliance with a particular kind of magic and spells in ways that are so much more convincing than that argument begun by Elkins.