Lynn Roberts-Goodwin's Arabian romance is longstanding. For some years now she has regularly escaped Australia to travel in places where women only appear in public covered top to toe in black burkas.

She has a long interest in cultures that cross boundaries. Her previous series was on falconry and the courtly culture surrounding the sport of these hunting birds. In the past she travelled to Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates to record the sacred release of the falcons, an event that unites desert peoples.

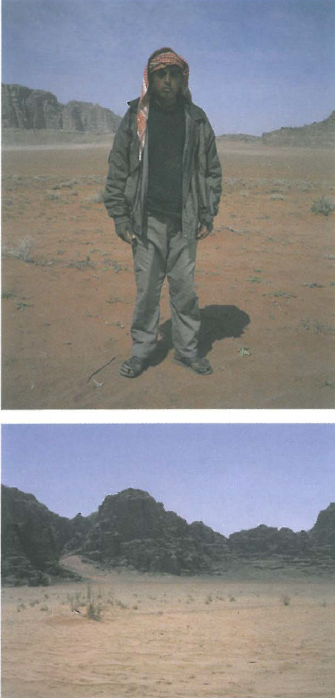

This latest exhibition comes from her Disappearing Act project which tracks the Frankincense trail, over the ancient lands that cross the boundaries of modern Oman, United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Jordan, Syria and Palestine. These particular photographs were taken in the remote valleys of Jordan, near Wadi Rum in Raiders of the Lost Ark country.

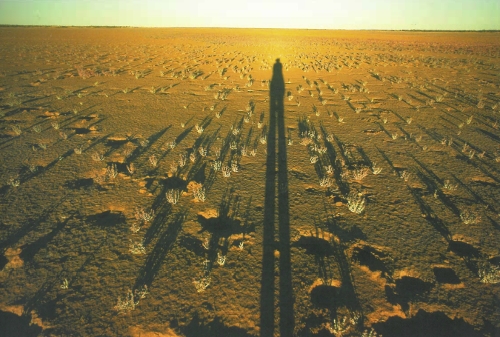

Disappearing Act plays on the Western imagining of the epic lands of ancient civilisations. The subject is the desert with its golden sands and massive mountains angled against the sky. It is both harsh and soft, the contrasts are both acute and subtle. Vegetation is scattered across the land, just enough to feed the ever-present goats and to stop the shifting sands from moving too fast. This is a place for epics. The armies of the ancient and modern world have failed to hold this place. Instead it remains the domain of its indigenous people, the Bedouin tribes.

These people, who once put their camels into the service of Lawrence of Arabia, are presented as matter of fact, direct portraits. Yousef and Muhammad, the petrol boys, and their unnamed friend stare at the camera with an analytical gaze. They are used to the admiration of their land. They know the petrol they bring will keep the photographer's car going. But they are free spirits. Their presence in the photographs serves another, more traditional purpose. Their bodies give scale to the landscape and make the viewer recognise that it is epic. These are her largest works to date, and the panoramic size suits the subject matter.

On one level these works quote the tradition of 20th century documentary photography, the style made popular by National Geographic with its romantic visions of distant lands. But the presence of the boys, and the deliberately low-key photographs of the decorated interiors of the Bedouin tents, also give an insight into a bigger question about the relationship between indigenous people and their land.

The way these boys are the owners of their landscape as they move across the world's most contested borders is a reminder that despite the best efforts of politicians of all nations, indigenous people still keep to their traditional ways. The Bedouin continue to supply the curious traveller, just as they did in the days of ancient Rome, but they are no one's servant. They have one pair of shoes, which they share. They like the toys, the gimmicks of modern machinery and fancy cameras, but they keep to the traditional values of desert cultures. In this sense the Bedouin have more in common with indigenous people of other continents – America, Asia, Australia – than they do with the city dwellers in their own region.

The portraits of the petrol boys have a quality of stillness that may be part of the photographer's art, or perhaps reflects a fascination with her equipment. The effect of these images however is to complement the sublime quality of the desert landscape, thus making these giant images objects worthy of contemplation. Beauty is the wrong word for these works. Sublime is more accurate, at least for the exterior images, while the photographs of the tent interiors have an exotic intimacy.