Memories are tricky things: deceptive, duplicitous, mercurial. Exposed to the corrosive properties of time they have a tendency to disintegrate, warp, attenuate. Memories are not stable; they are in a state of flux, a perpetual revisionist history, a never-ending work in progress.

Photographs play an important role in the fabrication of memories, especially in family histories where stories are repeated over and over again using family snapshots as mnemonic devices. This constant repetition blurs the borders between actual recollection and memorisation; photographs create an ontological chicken/egg scenario – which came first, the memory or the photo that represents it? Even though photographs and unreliable memories become inextricably entwined, photographs themselves seem beyond doubt.

Despite the inroads made by digital technology, photographs are still typically cast in the role of evidence. A photograph is a captured moment, light bounced off a particular scene, at a specific time and place, preserved in tasteful black and white or glorious colour; a photograph is proof. Photographs are seen as something firm, static, real, a means of fixing the constantly shifting boundaries of memory.

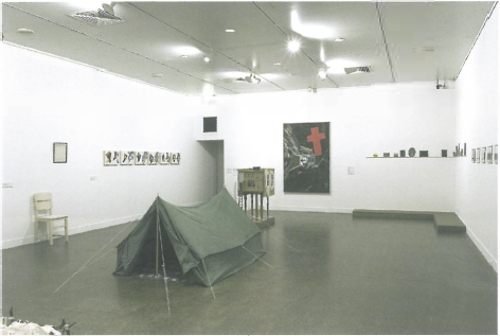

In his exhibition For Silvered Tongues Aaron Seeto deliberately undermines the stability of photography and highlights the mutability of memory. Since 2001, Seeto has collected old photographs of his Chinese ancestors and used them in his mixed media sculptural installations. He transfers these images onto silver cutlery and preserved duck eggs using nineteenth-century photographic processes. Seeto's photographs are prone to tarnishing and breakage; they are fragile and literally unstable. His images will change and become murky with exposure to time, just like memories.

Even though Seeto uses photographs of his own family to investigate personal stories and manipulate memory, his works also tap into a broader social history. Seeto's ancestors came to Australia, via Papua New Guinea, in the early years of the twentieth century. Visibly 'other' and determinedly different, early Chinese migrants to Australia were openly vilified, repressed and legislated against. Even though 'White Australia' is no longer official policy (replaced by the much friendlier catchphrase 'multiculturalism'), racist policy still finds favour in this country. Witness the frightening popularity of Pauline Hanson and her diatribes against 'Asians' and John Howard's rigorous defence of our national borders against a handful of refugees. Immigration is still a contentious topic, and negotiating an identity as an Asian-Australian remains a challenge. By using sensitively selected materials, Seeto's work examines these complex issues.

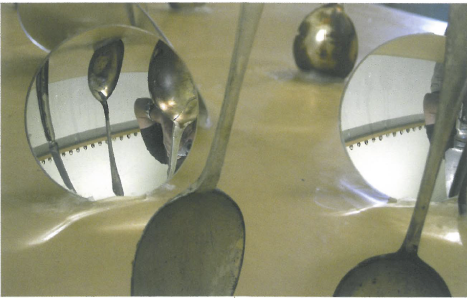

The Chinese who arrived the during the gold rush in the mid 1800s were really the beginning of Australia's multicultural society, but their role in shaping this country is largely unacknowledged. In Seeto's Missing series, photographs of his relatives are printed onto glass using the delicate watercolour albumen process. But their figures have been crudely cut out of the picture, removed from official history. In his wall piece, For Silvered Tongues, Seeto prints photographs of his ancestors onto silver cutlery. This title, a clever combination of 'silver spoons' and 'forked tongues', effectively conjures up images of deceit and class. The use of Chinese faces on luxurious domestic utensils seems to acknowledge the modern underclass of menial workers (often migrants) who service the privileged. Working as kitchen hands, sweatshop machinists and cleaners, their contribution to society is underpaid, undervalued and often invisible. In The Unseen, Seeto again uses photographs of his relatives transferred onto old-fashioned silver cutlery. He stands these knives and spoons upright in a thick slab of beeswax on an ornate wooden table. Concave mirrors behind each utensil reveal and distort the tiny portraits, like memories made hazy over time. At first glance this piece seems to be an evocative interpretation of family history that also marks a neat point of intersection between East and West, but it is both darker and more complex. The Chinese faces are not directly visible, they can only be seen through distorted reflections – a vision that is mediated and twisted.