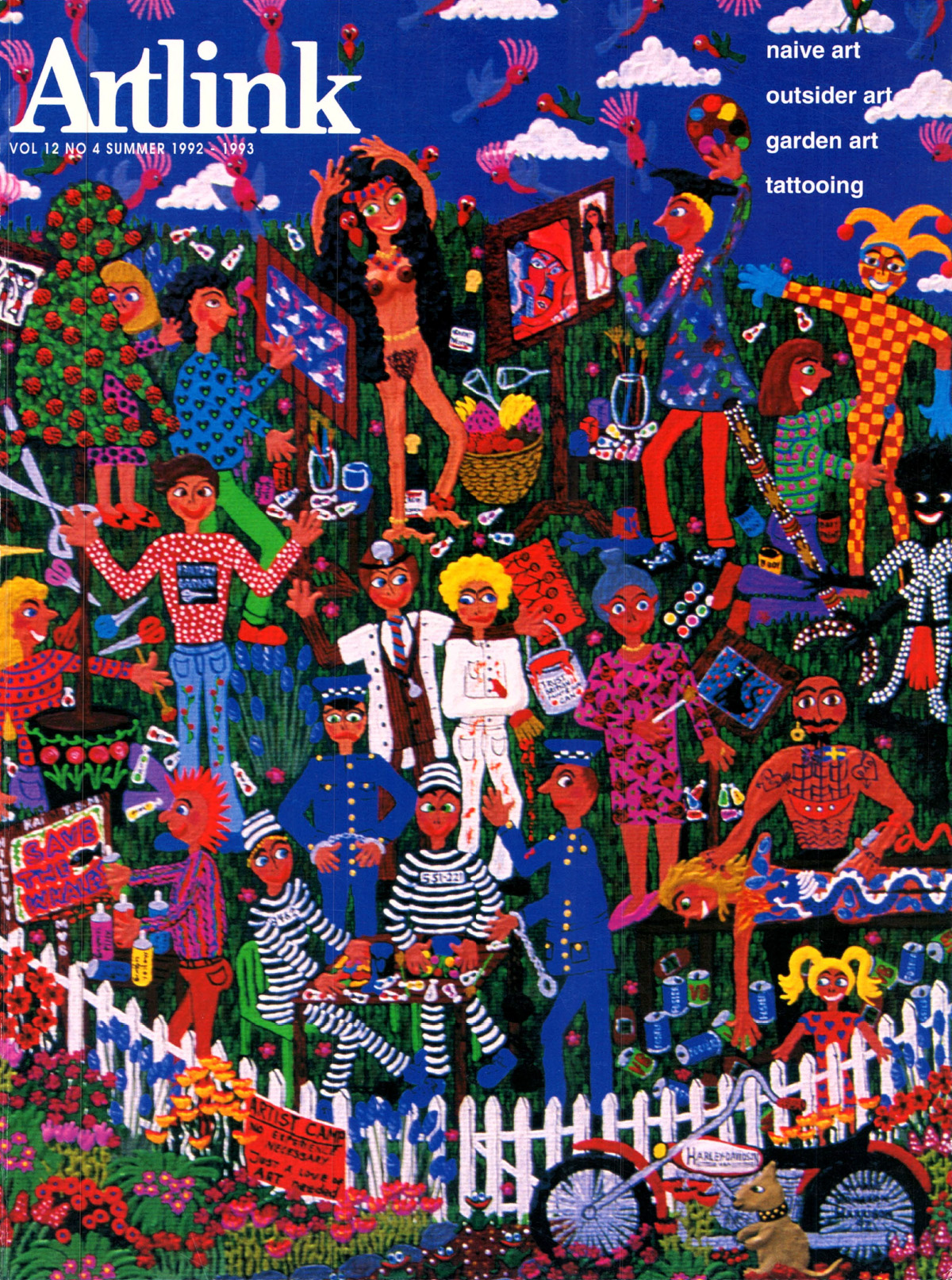

Naive & Outsider Art

Issue 12:4 | December 1992

This edition hails the power of the “Other”, those who neither claim nor require the validation of the art industry. It evolves from a raft of directions, supporting access and inclusion, community arts, postcolonial and postmodernist discourses, with a particular focus on the Global South.

In this issue

Arts Project Australia: Creativity, marginality and the politics of difference

A Living Treasure: The Topiary of Jack Cashion

As a sculptor working in metal I have been interested for some time in combining plants with the hard surfaces of copper and steel. The issues involved in using shrubs and trees are many, including that the work isn't trivialised or lacking in credibility, transport and of course storage.

Bill Sorrell

Looks at the environment of Bill Sorrell working in the small farming town of Toodyay in the Avon Valley about 80 kilometres from Perth Western Australia.

Captain Oates' Last Words

Art institutions are beginning to welcome Outsiders in. But there seems to be a little uncertainty in the art world as to the specifics of the Other guest list: enterprises such as this Artlink special issue are a means of establishing the canon, of packaging the concept.

Ciao from Canberra

Hidden in the neat suburban streets of Canberra are the sculptures of Giacomo Rampone. Superbly crafted from steel and cement, these sculptures adorn the front gardens of each of Rampone's homes past and present.

Disposable Icons

Tattoos

Eccentric Gardens of Australia

In country towns, suburban lanes and backstreets, tucked behind barricades and fences or alternatively displayed for all to see, are the gardens and decorated outdoor spaces of many 'other' artists. These gardens or 'exhibitions' could generally be called quirky. Many coloured photographs.

Foils for the Silver City

Disillusioned with the contemptible familiarity of our environment in the South Australian School of Art a group of fellow students and I decided to take our art somewhere else. So, displaced and gung-ho, our controversial creations in tow, we set off to Broken Hill, the self proclaimed art capital of Australia.

Frank 'Bronco' Johnson - The Poetics of Defence

He was always delighted to be fighting with someone....

From Stone Henge to Post-Feminist Creatures

Tattoo in Aotearoa/ New Zealand

Tattooing is not 'Outsider' or 'Other' art. To suggest this is to fall once more into the tiresome quagmire of Western art definitions. Looks at an exhibition 'Tattoo' 1993.

How to Hold a Festival in the Cook Islands

Make your moment in Pacific history and hang the cost. On 15 October 1992 Raratongans waited expectantly for their 2000 guests from 23 other Pacific countries to arrive for the 6th Pacific Festival of Arts.

I just had this Inkling...

Interview with Tazz a tattoo artist in South Australia.

Maria

Looks at the environment of Maria "Mad Mary" Hermann at her house in Leederville Western Australia.

Masterminded Masterpieces: Legendary Art

Mrs Iris Frame is going to be bigger than Elvis Presley. She told the author so herself. Her dream is to establish a museum of her life's work on her property just like Gracelands.

Mental Disturbance and Artistic Production

The popular understanding of the so-called 'insane' artist cannot be summarised better than in the schmaltzy lyrics of 'Vincent' written and sung by Don McLean in the 1970s. He plaintively chides those who misunderstood the living Van Gogh and charges them with the responsibility for his suicide.

Naive Archive

A national survey of Australian Naives - short biographies by various contributors as well as the artists themselves and images many in colour. Artists include Bernard Jeffery, Hugh Schulz, Bill Yaxley, Sam Byrne, Maitreyi Ray, Pam Bartley, Roma Higgins, Phyl Delves, Alison Vodic, Gwen Mason, Reny Mia Slay, Stella Dilger, Del Luke, Muriel Smith, Elfrun Lach, Susan Wanji Wanji, Miriam Naughton, Gwen Clarke, Selby Warren, Malcolm Otton, Harold Kangaroo Thornton, Ivy Robson, Lorna Chick and George Deurden.

Nothing if Not Innocent

Artists of the modern era have always been fascinated by the primitive, be it the obsession of the surrealists, futurists and modernists for the art of the Negro, the passion of a handful of British in the 60s for the work of the Cornish primitive Alfred Wallis or Jean Dubuffet's exploration of children's art and the art of the asylum which he termed Art Brut.

Now Who is Being Naive?

Naive is a tag used to describe the style of a particular artist and by inference the content of their work. In this examination of 4 contemporary artists working in what can be characterised as a naive style. the author illustrates that they are being anything but naive in the analysis of events, issues and stereotypes.

Nyungar Landscapes: Wetern Australia

In a remote corner of the south west of Western Australia, a school teacher who had never trained in art, was the catalyst for a school of landscape painting reminiscent of the style of Namatjira. Everything about this story was remarkable, not least that this happened over 40 years ago and that the average age of the artists was 10. The place was a tiny settlement known as Carrolup, now known as Marribank near Katanning.

Outsider Art: Flavour of the Month

Looks at the art market and the great beast of commercialism.

Stage Sets for Suburban Dramas

Photographs by Dianne Longley of domestic dwellings in and around Adelaide South Australia.

The Australian Collection of Outsider Art

Outsider Artists in Australia? Of course. The phenomenon is universal.

The Boundary Riders: The Art of Everyday Life

The diversity of work found in the art of everyday life transgresses many of the implicit boundaries about art practice laid down by the art world. Other art meets all the criteria by which we usually evaluate art works such as skill, commitment and self-expression yet is rarely seen in a gallery context. In order to recover meaning and value for the art of everyday life the question must be asked: why have these artists been marginalised by the art world?

The Chronic Population

Art Brut is that manner of making something whereby all of the individual is.

The World in Talc

Looks at the works of Talc Alf working in Lyndhurst South Australia.

Tut's Whittle Wonders

Written with David Wood. Explores the work of Tut Ludby who whittles wood in the small town of Strahan in Tasmania.

Anthony Hopkins

Looks at the works of Anthony Hopkins.

A Room of Their Own

Exhibition review Contemporary jewellery at the Jam Factory

Leslie Matthews "Inner Vane"

13 August - 13 September 1992

Cecelia Cmielewski 15 May - 5 June 1992

Jam Factory Adelaide South Australia

Arcanum (Extracts from the Archives)

Exhibition review Union Gallery

Adelaide University

South Australia

19 August - 4 September 1992

Desire Caught by the Tail: Jyanni Steffenson

Exhibition review it (ca) speaks...it (ca) sucks. "i(t) too was drag(g)ed into this sub-plot"

Installation by Jyanni Steffensen

Experimental Art Foundation

Adelaide South Australia

6 August - 6 September 1992

MFG: A Report on the First Eight Months of Greenaway Art Gallery

Review MFG: A report on the first eight months of Greenaway Art Gallery Opened in March 1992

Reflections on Being: Being and Nothingness

Exhibition review Being and Nothingness

Works by Bea Maddock

Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery

Launceston

August 1992

Self, Image and the Gaze: Anna Platten

Exhibition review Works by Anna Platten: Paintings and Studies 1982 -1992

University of South Australia Art Museum

30 July - 29 August 1992

The O/S Experience

Rediscovery: Australian Artists in Europe 1982-1992 Universal Expo Seville

June/July 1992

Curator Jonathon Holmes

Blue Bush, Blue Sky and Silver

Book review Blue Bush, Blue Sky and Silver Guide to artists and galleries of Broken Hill.

The Dictionary of Australian Artists

Book review The Dictionary of Australian Artists: Painters, Sketchers, Photographers and Engravers to 1870

Edited by Joan Kerr

Oxford University Press Melbourne

RRP $200

Tivaevae

Book review Tivaevae: Portraits of Cook Island Quilting

By Lynnsay Rongokea

Photographs John Daley

Published Daphne Brussell Assocs Press Wellington New Zealand