Recently my ancestral spirits allowed an exploration of Charlton Springs, the main sweet-water source in Kallinyalla near Port Lincoln. As my feet touched the aquifer, water bubbled above the surface like a fountain, creating a waterfall effect. The waters are now contained on private property, and have been since colonial times, but gaining access to this site where an old homestead once was, has been healing for my family. This is rarely the case for Aboriginal people today.

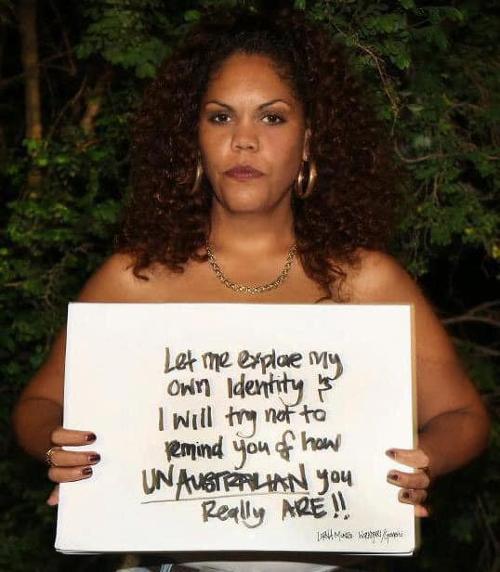

Growing up between Barngarla and Wongutha Country, there was nowhere I felt I belonged besides my family circle. It was hard for me to communicate in English. Generations of my family had to drop their cultural practices or die. This was the reality my grandparents survived: we were dispossessed from what is rightfully ours by colonial forces, including our sacred and life-giving waterways. Within three generations, we were barely able to explore and reconnect to our country. So imagine the mix of joy, pain and grief I felt the first time I heard my ancestors’ native tongue. Our languages are now accessible through the collaboration of linguists and survivors of our people to recover what was rightfully ours and to give to the next generations. Our languages and art are essential to cultural identity, the ways we think, do and live: we have been trained in this way for over 65,000 years.

Since language was stolen from my mob, the impact and toll it took on my elders and generations before has severed our connections to the spirit and the blood of Earth and water. It is this link that leads me to reflect on WATER RITES at ACE Open shown as part of the 2021 TARNANTHI Festival of Contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art.

For me, living and working out on Country, the work featuring the Barngarla language, Water Words developed by Galinyala Barngarla Artist Exchange is of deep interest. Some of my relations were involved in this exchange on Barngarla country, working with artists from Port Augusta and Adelaide and linguist Ghil’ad Zuckermann to collect words for water.[1] Spaced across the wall, the text reverses the normal order of English words, italicising the colonial language as though it is the ‘foreign’ word. The words are all interconnected with the theme of water-as-life, as it runs in our veins and cleanses our souls. Many different perspectives and aspects of water, from aquatic creatures to places and altered states of water are recorded, and each holds magnificent importance to the Barngarla people across the Eyre Peninsula. Personally, I can say being a part of this recovery process is a miracle for us youth.

Words also matter to Gamilaroi artist Archie Moore whose bittersweet and confronting piece Lake Massacre (2021) can be interpreted as a confession of sins committed in front of the water spirit. As he writes in his artist’s statement, these violent acts are ‘named by white people after acts they have committed there’. His installation of screens with water and words submerged behind frosted polycarbonate symbolise our struggles for life and water. The messages are distorted, forcing the viewer to crouch down below the works, craning their necks to read the word. In their discomfort, they learn the truth, the coloniser’s descendants learning the reality of the massacres of our people in their thirst for land and water.

For six years TARNANTHI has given our First Nations artists opportunities to speak truths such as this but also to entertain and to educate audiences. In this context, ACE Open and guest curator Danni Zuvela have provided a safe haven for experimental and yet provocative work that initiates hard conversations around our relationships with water.

One artist leading this conversation is Libby Harward, a descendant of the Ngugi people of Mulgumpin, Quandamooka/Moreton Bay. Her work Nangul Dabil Bungu explores a core concept of our human place within the water system and reminds us that we are mostly made of water. Through her own sweat and mud gathered from Kaurna Country (with permission from Uncle Mickey O’Brien), she honours ancient ceremonies for the water spirit in a very personal way, the trace of her energy contained in a water extraction unit in a symbol of ‘sweat money’.

The exhibition also speaks to the political strife amongst many communities and the exploitative sale of water from threatened river systems and underground aquifers in the virtual water market where mining, farming and human consumption all compete with the health of the river. There is competing morality between Indigenous worldviews and collective mindsets, the sustainability of Country for future generations and responsibilities and duties to both ancestors and descendants. These contrast with political and economic views of water as a resource to be exploited and consumed. We see suppression of the women/water spirit and the greed that is expressed in taking more than you need.

When I first saw the work by palawa artist Mandy Quadrio, who weaves kelp and steel wool to create her forms, I thought of baby mermaids hidden in their own darkness on the ocean floor, so sailors can’t hunt and rape them. The sculptures are open to interpretation due to the many organic shapes they take in contrast to the more geometric and architectural works in the gallery; many other viewers have seen shapes of the divine feminine, an innocent baby, reaching hands, anchors, a tall ship. How you see is simply a reflection on your relationship with water. All is possible through the strong organic materials that contrast with more geometric forms of the other works in the gallery.

WATER RITES comprises installation and assemblage, accompanied by surreal sounds and vivid moving image works: there are ten films from across the world presented alongside these local expressions of the sacred and scientific ecologies of water. It reminds me that the Earth’s most precious commodity is something so pure and simple that we as a species can overlook it until it’s too late. These stories and experiences with the core water spirit prove that we all have a relationship with water whether we are conscious of it or not. This bond is sacred and should be celebrated, even if it’s a simple thank you prayer every time we interact with water. These artists are trying to convey the importance of respecting our water. In some ways, the exhibition transcends my usual experience of art as it explores water ‘as culture, concept and commodity’. But what I do know is the intergenerational inheritance of First Nations peoples and our continuing fight to look after our people, our Country and our water.

Footnotes

- ^ Artists involved in the exchange were Vera, Jenna and Evelyn Richards, Candace and Caitlin Taylor-Swan, Henry Jock Walker and Emmaline Zanelli.