I always go back before I go forward with my culture.[1] Colin Walker, Yorta Yorta Elder

Coranderrk was a former Aboriginal Station established in 1863 to ‘manage’ and ‘civilise’ the Aboriginal populations who were being subjected to the unchecked, unauthorised white patriarchal greed running rampant across our Country. The site exists in our collective experience—Aboriginal or otherwise—as one of the first reserves established in the state of Victoria as part of the colonial processes that controlled Aboriginal peoples’ lives.[2]

Today, Coranderrk occupies an important position in the living history of the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin nation. It is also an important place in the collective memory of many Aboriginal people from the south-eastern areas of our Country, who have traditional, ancient connections to other territories, beyond the borders of Kulin Country.

As a Yorta Yorta man, I recognise the ongoing connections many of us have to Coranderrk, situated some seventy kilometres northeast of Melbourne, on the unceded land of the Wurundjeri people. Understanding Coranderrk’s relevance in our collective history as south-eastern Aboriginal people is to begin to access some of the rare and important insights offered in WILAM BIIK at TarraWarra Museum of Art. Coranderrk is a relational and conceptual motif of shared experience which forms an important foundation to WILAM BIIK, ‘home Country’ in the Woiwurrung language of the Wurundjeri.

Curated by Stacie Piper (Wurundjeri, Dja Dja wurrung and Ngurai illum-wurrung), WILAM BIIK is a reverberating experience for us—and I speak for an Aboriginal experience here. The exhibition is a tender and resilient insight into a range of south-eastern Aboriginal nations that explores family histories, art, culture, reclamation and continuity, that either directly stems from, or forms a respectful solidarity to, the unceded land of the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin nation.

WILAM BIIK starts with a simple dichotomy that balances the past and the present. Piper’s choices in what I consider to be an introductory Wurundjeri gallery are a powerful interplay of reflection and forecast. Exploring this interplay is to begin by reading—as is dictated by the western tradition—from left to right. Whether that’s a nod to the dominant cultural paradigm or a buy in by way of subverting it, remains for viewers to interpret within the relationships that art has to the galleries and architecture it is presented in.

The left wall in the first gallery features a photograph of the landscape of Coranderrk enlarged to become a feature wall. The historical photograph of this government-controlled place, so familiar to so many of us Aboriginal viewers with its sepia tinge, speaks to us by way of introduction, like a cursory nod to an Aboriginal past once considered static.

Piper asks us to consider this past: we’re invited to ponder the lives of the Aboriginal people that feature on the large gallery wall. The ancestors in the picture stand still—posing, frozen as the camera from that bygone era demands. The effect of the feature wall is detached and unnerving, creating a tension between the austere image of Coranderrk’s past and the monumental interior space. The photograph of Coranderrk and its inhabitants is composed: the Aboriginal people within are effectively on display. They speak without sound from the colonial frontier and are re-presented so that we reconsider history and how such legacies are created on home Country.

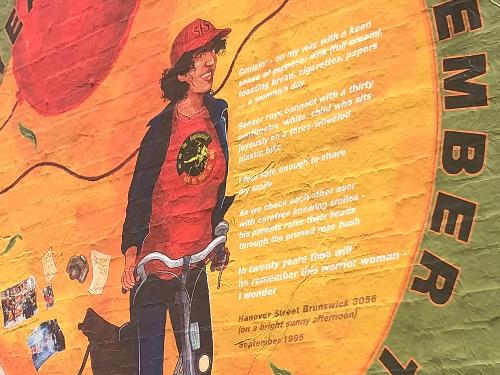

The people of Coranderrk past are bound by a series of wooden fences that demarcated their lives on the former Aboriginal station. Behind them is the grandeur of the Wurundjeri and Gunnai/Kurnai hills. The opposite wall features looped audio-visual footage of the Djirri Djirri Wurundjeri Women’s Dance Group, projected onto a large wall, bringing the lush green of Wurundjeri Country inside. The performers offer a lively full-colour contrast, a moving, singing, resilient rebuttal to the historic Coranderrk photograph. Djirri Djirri means ‘messenger’ in Woiwurrung, and the women’s dance group’s movement, song and ceremony depict their sovereign past and present, claiming an unbridled future.

Between these two opposing walls are artworks, and what many may call cultural artefacts, that serve as an inviting and elegant celebration of living Wurundjeri (Woiwurrung) and other south-eastern Aboriginal cultures. Featured are a range of accessories that would ordinarily adorn a Djirri Djirri dancer as they practice ceremony in the now; other items, sourced from the collection of Museum Victoria, include an emu feather skirt (c.1880s), a women’s digging stick from the nineteenth century, and an exquisite basket woven over a century ago by Granny Jemima Burns Wandin Dunolly. Poring over these items helps us realise the echoing, adaptive resilience that Piper presents in WILAM BIIK.

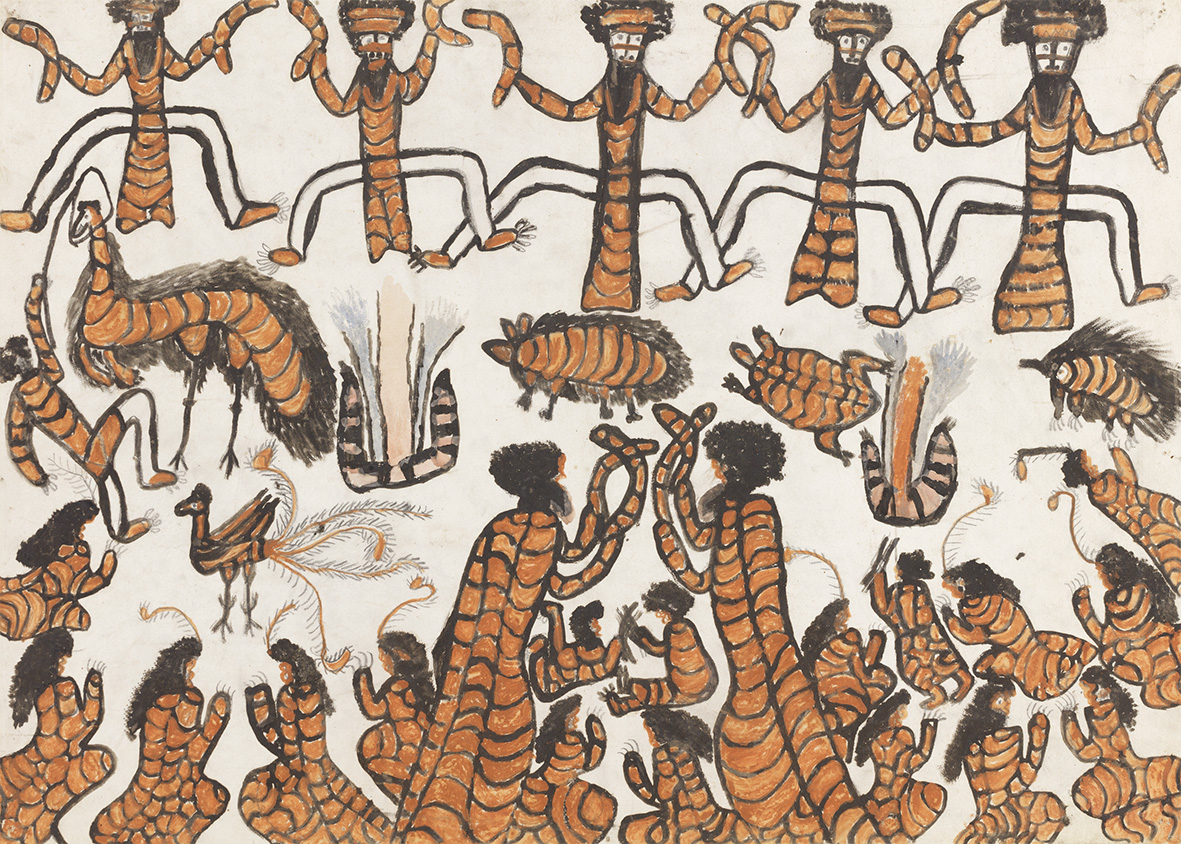

Famed Wurundjeri Ngurungaeta artist and leader William Barak features alongside works by many south-eastern Aboriginal women in what amounts to an intergenerational display between ancestors and living descendants. Barak’s five works on paper and card, rendered in ochre, natural pigment and charcoal ranging from the 1880s to c.1900 feature corroborees, wildlife and animated ceremonies. I’ve only ever seen these works reproduced in publications, and they’re a precious and meaningful addition to the narrative within WILAM BIIK.

I understand Barak also features as one of the ancestors in the sepia photo of Coranderrk. Barak’s legacy is again honoured in the same room by Wurundjeri artist and traditional weaver Kim Wandin. Four sepia portraits of Wurundjeri ancestors Jemima Burns Wandin Dunolly, Robert Wandoon, Annie Borate and William Barak feature in frames of rescued Victorian Mountain Ash. Each framed photograph is bound by natural fibres woven meticulously and with evident warmth by Wandin. The woven frames hug each portrait with a charming organic ease that makes standing before them a touching and reverential experience. While the weaving materials are green, and in time they’ll lose their colour, the meticulous technique of the Woiwurrung creative tradition remains.

The next gallery allows us to explore the home Country of other Aboriginal nations from the south-east, by way of echoing and expanding on the material in the introductory gallery.

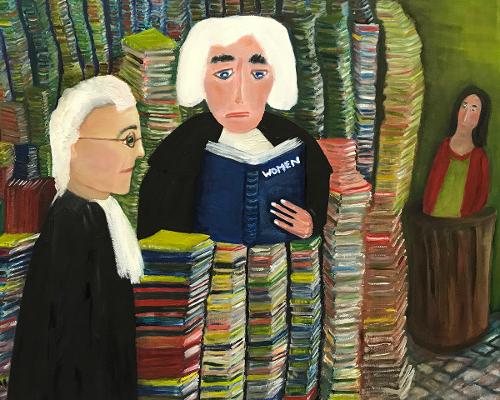

Paola Balla (Wemba Wemba, Gunditjmara) builds upon a series of works she presented in Disrupting Artistic Terra Nullius at Footscray Community Arts Centre in late 2019. Then, Balla effectively and deftly disrupted the Australian application of terra nullius on Aboriginal sovereignty by offering insights centred on the steady strength and resilience of the Wemba Wemba women in her life. Balla has also explored her own steady strength and resilience in her art as a subject in self-portraiture within a long line of Blak Matriarchy. In WILAM BIIK, Balla creates an artistic and cultural continuum that pays direct homage to her maternal Grandmother Rosie Tang.

Core to Balla’s installation is a small oil painting by Tang. The frame is colonial in style: austere brown wood that features faint strips and fine flecks of gold leaf. The painting is enlarged and becomes a backdrop to Balla’s installation. Tang’s proud white gum tree, with its deep green leaves, arcs across one wall—again from left to right—to create what for all intents and purpose is the perfect campsite. A river meanders across the centre of the landscape. Distant hills feature in the background like a direct visual quote from a Namatjira watercolour.

This cherished family painting becomes a campsite, replete with a bough shed of bush-dyed silk organza that’s mottled with the stain and scent of eucalyptus, lilly-pilly, bottlebrush, native lilac and other bush flora. The golden flecks of Balla’s grandmother’s wooden frame are echoed in the gold-leaf words inside the bough shed that spell out ‘kuku lar’ meaning ‘nan’s camp/place’ in Balla’s Wemba Wemba language. The installation is humble, intimate, inviting, both healing and grounding as only home Country can be.

.jpg)

Taungurung artist Steven Rhall’s work also takes foundation in the representation of Country, with a telling consideration of the gallery he is exhibiting in. A colour photograph of a rock formation in a clean, pale wooden frame invites the viewer to see Country contained. Behind the white wall displaying the photograph is an enclave: inside are plaster walls, some of them unfinished and raw. On the rear wall a hole has been sledgehammered, rough and jagged, as though by the hand of someone resisting confinement. Inside the jagged gap is the rock formation image presented on a wooden table, unframed, and weighed down by a rock on each corner. A dull reverberating soundscape makes the re-presented rock formation image hum and vibrate: it’s alive, unlike the austere rammed earth structure of the TarraWarra Museum of Art.

Peering in on Rhall’s installation reminded me of A Tribute to The Concrete Box (For Aunty Hyllus Maris), by Yorta Yorta artist Moorina Bonini with Bus Projects at the Collingwood Yards in 2020. Comparing the work of Rhall and Bonini allows us to see an unequivocal comment on the containment of Aboriginal lives in colonial Australia, and in turn we’re left to consider survival and hope as powerful alternatives.

The most exciting aspect of WILAM BIIK, in my experience, is that offered by Arika Waulu (Koolyn, Djap Wurrung, Peek Wurrung, Dhauwurd Wurrung), whose work amplifies and compounds the Blak Matriarchal theme woven throughout WILAM BIIK. Centred in Waulu’s installation are two huge kanak/kalla (digging sticks) made of wood, pokerwork, emu fat and gold that hang above a circle of earth surrounded by rocks. The kanak/kalla, though still, appear to be dancing; the angles they’re positioned in suggests movement and grace, suspended in the space to echo the Wurundjeri hills outside. Within the gallery of TarraWarra, they help sing a time-honoured song spanning millennia, of connecting with home Country and living with reciprocity and respect.

There’s nothing urgent in the curatorial and cultural benefaction offered in this exhibition. Aside from Rhall’s installation, there’s not a trace of an asserted cultural statement that could be considered forthright, or a radical juxtaposition to colonial Australia. Collectively, the pieces that make up the show are graceful, tempered, assured and exemplary. All the art and culture that is on show in WILAM BIIK forms an inviting and time-honoured culmination of our home Country’s knowledge, insight, experience, and wisdom; that in turn serves as a unique collective opportunity allowing us all to look forward by looking back.

Footnotes