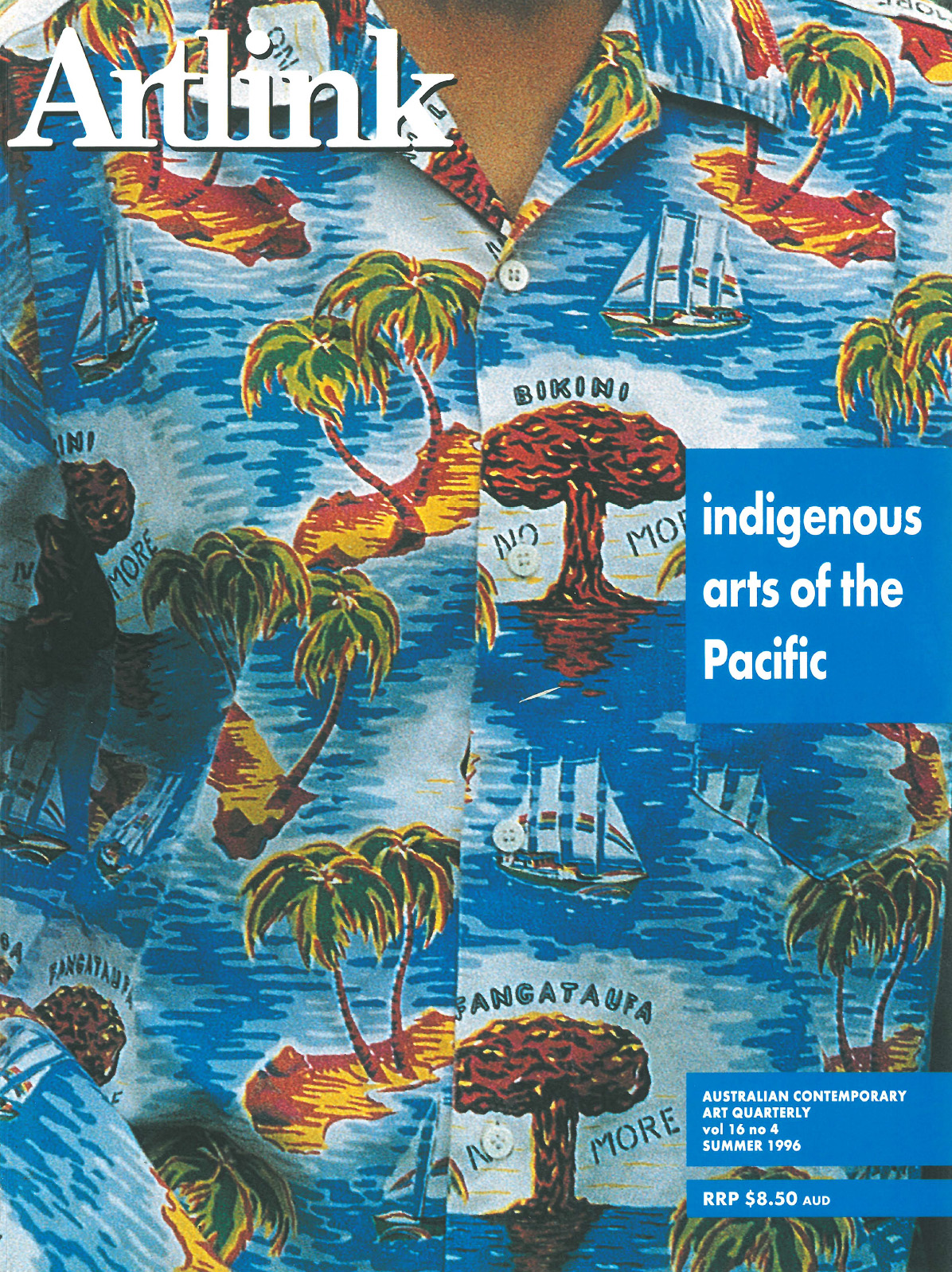

Indigenous Arts of the Pacific

Issue 16:4 | December 1996

Examines contemporary issues facing communities in the Pacific region. Art and economics, cross-cultural issues, politics and subsidy, festival and promotions are included in the overview which looks at Australian indigenous art, Maori art from New Zealand, art from Papua New Guinea, Cook Islands, Fiji, Samoa.

In this issue

The Land made Visible: Native Title Now

Written with Vincent Megaw. Looks at land claims and the role of artworks in these claims in the context of the exhibition 'Native Titled Now' shown as part of the Telstra Festival of Arts 1996. Good overview of indigenous art practice and talks about artists such as Raymond Arone Meeks, Lin Onus, Gordon Bennett, Alice Hinton-Bateup, Avril Quaill, Kerry Giles, Daphne Naden, Mick Namarari, Turkey Tolson, Danie Mellor, Jonathan Kumintjara Brown, Clifford Possum, Ellen Jose, Lindsay Bird Mpetyane, Heather Shearer and Kathleen Wallace.

An Alternative to the Art Market

The market must acknowledge its role in the commidification of indigenous cultures through cultural objects....What the market must acknowledge is the relationship of interdependency which exists between itself and the artists that it promotes and as such, the market must ensure that its actions do not prove detrimental to the artist and the community in the long run.

Tandanya - Captivating Culture

Brief overview of the current focus of Tandanya the National Aboriginal Cultural Institute in Adelaide, South Australia.

New Developments for the Papua New Guinea National Museum

Brief article outlining the current directions and focus for the PNG Museum and Art Gallery in Port Moresby.

Art is Land: Land is Art - Talks with Banduk Marika

Discussion with the artist Banduk Marika about the issues facing her community of Yirrkala in Arnhem Land, Northern Territory. Indigenous art practice and land rights, cultural heritage, education and knowledge, environmental protection and mining intrusions are discussed.

The Waka and the Cattle Truck

What do a traditional Maori canoe (waka) and a cattle truck have in common?...In both these cases these vehicles were conveyors of culture. These images are central to two collaborative works at the second Asia Pacific Triennial of Pacific Art at the Queensland Art Gallery.

Pacific Wave: A Festival of Pacific Arts

Brief article outlining Pacific Wave, a celebration and investigation of contemporary trends in art and cultural life of the Pacific taking place across Sydney November 2-17 1996.

Nucleus: Feeling Compromised

As Judy Watson was about the commence her residency in France, the French Government announced they would be conducting nuclear tests in the Pacific. As an Australian, an Aboriginal, a conservationist, a woman and an artist, she felt compromised. Discusses her work in this context.

Maori Film Images and Intellectual Property Rights - A Breakthrough?

For those depositing films with a significant Maori content, the New Zealand Film Archive has developed a Deposit Agreement which acknowledges that named Maori guardians have spiritual guardianship authority over their image treasures in perpetuity. This goes way beyond white copyright regimes.

Contemporary Maori Architecture - The Case for the Untraditional

One of the most insidious myths about contemporary Maori architecture is that it does not exist, since 'traditional' Maori building design has been influenced by colonial architecture. Looks at contemporary issues in Maori architecture.

Taki Rua: Bi-cultural Theatre in Aotearoa

Taki Rua Theatre has been at the cutting edge of indigenous theatre since its inception in 1983. It has now produced a season of Maori plays in te reo Maori (Maori language).

Telling it How it is: Pacific Islands Theatre in Aotearoa New Zealand

Pacific Islands Theatre is at an exciting phase in New Zealand. Although relatively young compared to Maori and Pakeha theatre, the debut of key successful plays has placed it in the spotlight of New Zealand's national stage in recent years as it continues to gain strength.

The Art of Survival: The Importance of Contemporary Theatre in Papua New Guinea

In many developing countries where indigenous communities are faced with the rapid process of development, theatre has become an extremely important educational tool. With escalating resource exploitation, rising numbers of sexually transmitted diseases and AIDS and increases in violent crimes by an unemployed and disillusioned youth, the importance of this form of communication cannot be underestimated.

Polynesian Tattoo: A Shift in Meaning

Tattoo played a significant role as a marker of status, wealth, and pride in Polynesian societies. A more fluid, creative tattoo tradition is being practised today.

Creativity in the Forest

In 1994, the small Balai community of Malaita Province, Solomon Islands, commenced paper making which led to the development of printmaking. Small enterprises and ecotourism may well be the future of these small island communities.

Spirit Blong Bubu I Kam Bak [The Return of the Spirits of the Ancestors]

Reflections on an exhibition in Vanuatu of old pieces of ni Vanuatu art held in European collections. Touring Exhibition 'Arts of Vanuatu' 29 June - 10 August 1996 at the National Museum of Vanuatu in the national capital of Port Vila.

The Contemporary Highland Shield: Hybrid Forms in Papua New Guinea

The author examines shield collected in 1995 to discuss issues fundamental to the introduction of the art of emergent societies in an international art context. Issues such as the definition of art and aesthetics, art versus craft, function of art in the various contexts etc...

Oceanic Arts Society of Sydney

Describes the establishment and membership of this new society.

Acting Out the Culture: The Making of Culturally Relevant Theatre, Papua New Guinea

Culturally relevant theatre in education in Papua New Guinea challenges, questions, asserts, transgresses, subverts, opposes, resists and negotiates with the demands of political and cultural relations. It offers new forms of representation and contributes to the process of destabilising and decentering the domination of Western processes of teaching, learning and performance.

Art and Ritual: Aina Asi A Mavaru Kavamu

The artist writes of the issues facing her as a citizen of Papua New Guinea, a descendant of the Motu Koita people, being female and an artist/textile designer. Her traditional grass skirts were included in the Asia-Pacific Triennial.

Weaving the Old with the New: Textile Art Forms in Niugini

Women artists were conspicuously absent from the important exhibition 'Luk Luk Gen'. The exhibition 'Pacific Dreams' included textile works by the artist Agatha Waramin who works with bilums and the exhibition 'Weaving the Old with the New' will extend women's exposure in an artistic context.

Dancing the Society: Performing Arts in the Solomon Islands

Performing arts in the Solomon Islands Since the common determining facts in whether to keep, add changes, or reject aspects of the performing arts are based on the dollar, Solomon Islanders will continue to adopt new styles of dances, music, songs and forms of acting in the same way as some Church groups have done.

Educating Public Taste

The National Museum's role in the development of contemporary art in the Solomon Islands. Artists Dick Taumata, Kuai Maueha, Frank Haikiu, Rex Mahuta, Jack Saemala and Billy Vina are discussed.

Pacific Stories from New Caledonia

Collecting Pacific Art is not a straight forward endeavour. There are really no set criteria of what 'contemporary Pacific art' might be, little interpretive literature on the subject and very few precedents for forming even small collections for cultural institutions. There is a new cultural centre 'the Jean-Marie Cultural Centre' being built in Noumea, New Caledonia.

Soapstone Workshop

April 1996 at the Pouebo Town Hall northern New Caledonia. A sculptural tradition has always been alive in this area so a workshop was held to explore the use of soapstone sculpture.

The Island Race in Aotearoa

Today the art of the Pacific Islanders is still trapped within its category. The display cases of the institutions have not been shattered. Yet the very act of exhibiting demonstrates that the making and the appreciation of art is a dynamic process. Institutions are caught by a need to both legitimise themselves and acknowledge (and perhaps attempt to control) the art of the migrant communities.

Vaka - Only the Brave

Looks at the contemporary art and the cultural and economic pressures faced by the people of the Cook Islands.

Fiji: Artists Carve Out Their Own Future

Looks at issues in contemporary art practice in Fiji anticipating the construction of the new Fiji National Art School.

Asia and Oceania Influences - Sydney

Exhibition review Asian and Oceania Influence

Curated by Nick Waterlow

Ivan Dougherty Gallery, Sydney

2-30 September 1995

The World Over - Wellington

Exhibition review The World Over

City Gallery Wellington, New Zealand

June 8 - August 11, 1995

Darwin Festival - A Glimpse

Overview of the Festival of Darwin with its temporary visual art installations 'art head land' by 18 artists. For the summer of 1996.

Australia Goes to Samoa: 7th Pacific Festival of the Arts

Overview of the 7th Pacific Festival of Arts which is held in a different country every 4 years. 1996 the festival was held in Apia in Western Samoa. Previous hosts 1992 Raratonga, Cook Islands 1988 Townsville Queensland Australia Lists the communities of Aboriginal Australians who were in attendance at the festival.

Alternative Festival in Samoa

An alternative festival celebrating the people of the Pacific was held on one of the outer islands (Manono) in Western Samoa at the same time as the official Pacific Festival of the Arts in Apia. The festival was conducted from 8-23 September 1996.

Collaboration - Zhou Xiaoping and Jimmy Pike

Chinese Australian artist Zhou Xiaoping and Aboriginal artist Jimmy Pike exhibit collaborative works in China later in 1996. The author discusses Zhou's new work and his collaboration with Jimmy Pike.

The Necessity of Craft ed Lorna Kaino

Book review The Necessity of Craft: Development and Women's Craft Practice in the Asian Pacific Region

Edited by Lorna Kaino

University of Western Australia Press 1995

RRP $24.95

Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia ed David Horton

Book review Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia with companion CD Rom

Edited by David Horton

Aboriginal Studies Press for AIATSIS

RRP $150

Doin' the Limbo

Exhibition review White Hysteria

Curated by Susan Treister

Contemporary Art Centre, Adelaide South Australia

7 - 30 June 1996

Whetting the Appetite

Exhibition review State of the Art 4 Biennial survey exhibition

curated by Stephanie Radok

New Land Gallery, Port Adelaide South Australia

21 April - 12 May 1996

The Silence which Howls

Exhibition review Second Look: Prospect Textile Biennial

Prospect Gallery

14 April - 5 May 1996

Funk Junk

Exhibition review Junk Bonds

New Land Gallery, Port Adelaide South Australia

Touring South Australia and interstate with Visions of Australia

28 June - 28 July 1996.

Truth, Whose Truth?

Exhibition review Peter Dailey: Prime Time

Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery

University of Western Australia

17 May - 30 June 1996

Memories - Macabre and Magic

Exhibition review Aadje Bruce: Domestic Bliss

Artplace Claremont Western Australia

9 May -1 June 1996

Resilient Modernism

Exhibition review Miriam Stannage and Tom Gibbons

Goddard de Fiddes

Contemporary Art Perth, Western Australia

2- 22 June 1996

From the Back Shed

Exhibition review House and Home

Anne Neil and Steve Tepper

Fremantle Art Centre galleries,

grounds and craft shop

25 May - 16 June 1996

Neo-colonialist Precipice

Exhibition review Secret Places

Sieglinde Karl, Hazel Smith, Kate Hamilton, Ron Nagorka

Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery,

Touring regional Australia through Contemporary Art Services Tasmania and the national Exhibitions Touring Scheme.

Touch Don't Touch

Exhibition review Tangibility

Claire Barclay, John R Neeson, Stephen Bush & Jan Nelson Plimsoll Gallery and Powder Magazine, Hobart

10 - 31 May 1996