There are so many aesthetics theories piling up these days: systems aesthetics, post-media aesthetics, relational aesthetics, cybernetic aesthetics, causation aesthetics. This is no coincidence. In an era of rapid technological change, it makes sense to reassess the way we interact with art concepts and art objects, and times of flux encourage the generation of new theories. The 2013 International Symposium of Electronic Art (ISEA), Resistance is Futile, proudly hosted by College of Fine Art in Sydney, exposed some of this art aesthetics flux.

After seeing a large number of ISEA exhibitions and talks, it would be easy to herald the application and incorporation of new digital technologies, such as computer science, systems of geometry, generative algorithmic mathematics and new interactive software, to art and leave it at that. However, as curator and art writer Claire Bishop noted in a 2012 article in Artforum, contemporary art simultaneously depends upon and disavows the digital revolution.

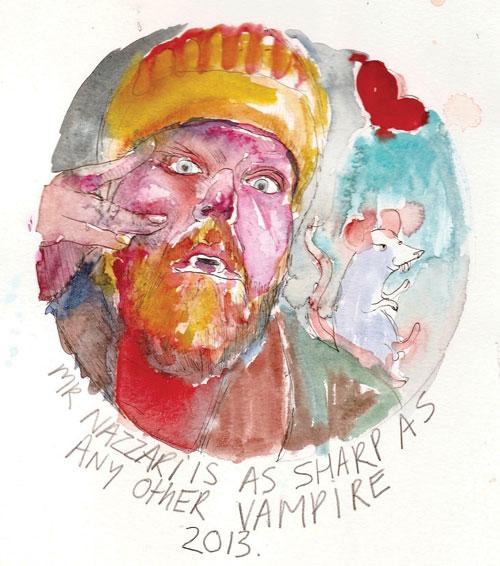

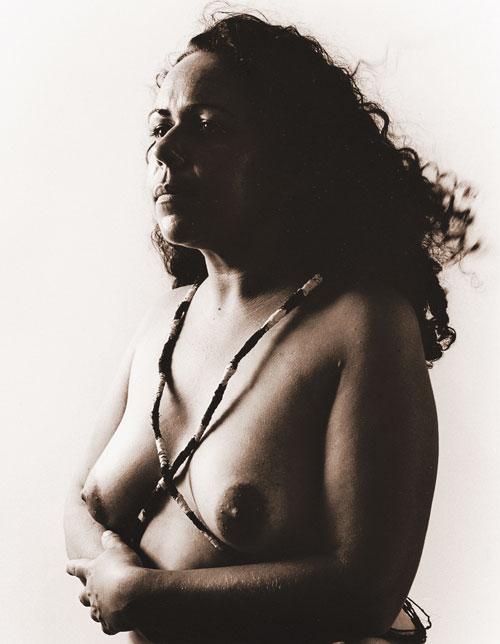

This ambivalence towards technology, by the artists using it and by institutions exhibiting it, is interesting. There is a stubborn inclination to defend the primary quality of the artist’s hand; the individual, the embodied and haptic sensibility of the human. This might be a pathological fear of mortal extinction or it might be a wish to remain focused on first principles of art historical practice. Either way, it’s a paradoxical phenomena: to defend against the potential artificial intelligence of the technology, to which we are addicted.

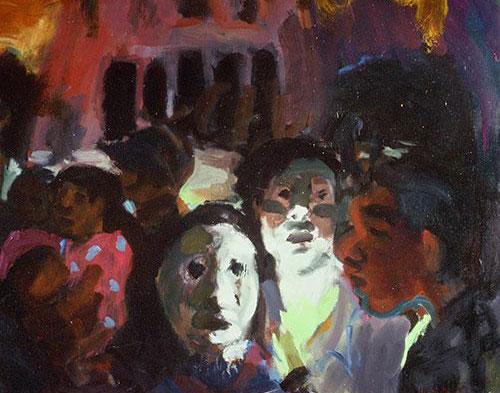

ISEA 2013 comprised many events, talks and panel sessions. A highlight was the Ryoji Ikeda installation at Carriageworks. Ikeda collaborated with scientists and pure mathematicians to generate algorithmic data from various digital sources. These codes and equations were then adapted into sound and lighting. Strobe lights flashed across the floor, like bar codes, and high-pitched sound assaulted audiences from surrounding speakers. Also at Carriageworks was Alex Davies’ The Very Near Future, a curious and sophisticated study of the slippages between fact and fiction, between reality and ‘‘reality shows’’. His playful use of surveillance to comment upon itself was resolved and, after opening many doors, many times over, left me feeling confounded and strangely happy.

Robots and other automata scuttled around the ISEA events, like mythical beasts, sent to nip our ankles and create wonder, regarding our perception of truth. So, although data analysis, simulations and systematic protocols of art were at the heart of the ISEA initiative, it was often those cute little robots that stole my heart. Petra Gemeinboeck’s Accomplice at Artspace involved a track behind a hidden wall along which robots moved and banged their machinic fists, making holes and causing devastation, not unlike unruly human toddlers. Margaret Seymour’s Tracker at Articulate Space was another commentary on surveillance, as video objects trailed after visitors, recording their moves. Footage was then enhanced with film noir-esque software to create that gritty spy movie appearance, and to introduce some dark romance to a hot and potentially malevolent global issue.

COFA’s Kudos Gallery offered a surprise package of engaging electronic media. Volker Kuchelmeister’s interactive video installations blurred the limits between our perception and our memory of experience. His dromological vision machine combined nostalgic ocular optics with futuristic visions of a world without borders. When you turned the handle of a moving drum, nations merged and cultures became equalised as you watched successive horizontal footage of various cities and landscapes of the world. Chris Henschke’s animation of a three-dimensional model of a particle collider offered kaleidoscopic impressions, in a gorgeous spectrum of patterns and colours.

While new technology facilitated most of the artwork (and fueled the discussions) in the ISEA events, it was also an entity to be defined and even packed away, to allow the audience’s ‘‘true’’ art experience to work. Passionately debated topics of agency (the power of inanimate objects to act), relations (the inter-connections between objects and humans, in the context of socio-politics and culture) and emergent behaviour (when data is recorded from audiences but also changed by it) were present in many of these works. Yet audiences were still allowed space to interact and immerse with the art itself. These kinds of phenomenological and embodied experiences remain constant in art and aesthetics, thank goodness.