In-flight (Project: Another Country) made Alfredo-Juan Aquilizan and Isabel Gaudinez-Aquilizan into two of the heroes of GoMA's 2009 Asia-Pacific Triennial. It was a work that managed to involve children from all over the state to make a huge mound of amazing flying machines out of odd pieces of cast-off material. It was so enticing that it brought children and adults alike into its orbit. This meant that the pair were a logical choice for Gene Sherman’s Contemporary Art for Contemporary Kids SCAF project in 2010 as the APT success was replicated in an intimate interactive context for the pleasure of children in Sydney.

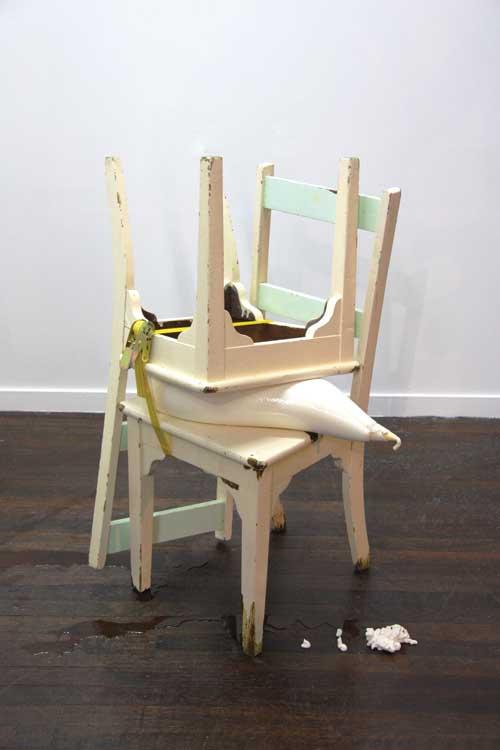

In-Habit (Project Another Country) revisits the interactive nature of the earlier work, but the message is both more emotionally involved, and more sobering. And yet there is a lightness and joy to it all. The artists have made a combination of videos and miniature cardboard houses to present the lives of the Badjao, the "sea gypsy" Muslim people who live as cultural outsiders on the southern fringes of the Catholic Philippines. For hundreds of years they have lived in boats, fishing and floating in the waters from Malaysia to the Philippines. Their transient life has made them especially vulnerable to the ever-expanding land-based cultures, and their traditional fishing life is under threat from commercial operations. The particular community that Alfredo-Juan Aquilizan and Isabel Gaudinez-Aquilizan worked with in creating In-Habit have moved off their boats into huts rising on stilts from the water around Davao, that are perched insecurely in-between sea and land. It is a precarious way of life, as reflected in the thin bamboo poles that hold the high huts (made of sticks and leaves) away from the water. One decent tropical storm and they will be blown to smithereens. But still the Badjao persist in behaving with such joie de vivre that their pleasure in the simple elements of life is almost overwhelming. Tiny children play in the water with as much confidence as if it were solid land. They use a discarded refrigerator as a boat, and squeal with joy when it is upended. For the most part, the videos installed throughout the exhibition give the sound of singing; not folk songs that may belong to such an ancient race, but cheeky rap made with a strong drumbeat, taken straight from modern electronic music. There is of course a twist: the singers are tiny children, singing to the background of the sea, not urban grunge, and their home-made drums are cardboard tubes covered with tin foil. The intensity of the colour from the video screen contrasts with the cardboard boxes used to make the hundreds of tiny houses that are the constructed exhibition.

Just as the videos are collaborative work, so is the installation. The artists worked with school children over some weeks to make the tiny imagined houses that hang from the ceiling and tumble over the walls in apparent total anarchy. Then they invited all and sundry visitors to sit at a cardboard desk and, using cardboard, string and sticks, to make their own little house, which may either be taken home or joined with existing works on view. So the exhibition grows.

It would be easy to romanticise the life that these children lead, splashing in the water, singing happy songs for the pleasure of tourists. But one of the people interviewed gives a more realistic picture. Life on the edge is hard. They are in effect refugees, without rights, dependent on the whims of the people of the land, who do not necessarily welcome them. The drums and the rap music are a recent invention, sung at Christmas by children who do not believe in such alien festivals.

This then is the reason that Alfredo-Juan Aqulizan and Isabel Gaudinez-Aquilizan have chosen them, because as artists from the Philippines living in Australia, they too are fringe dwellers and strangers in a strange land. They know the sense of transience that governs the lives of immigrants, who feel the land may not be theirs by right, and so must move on. They also understand the value of such a fragile existence, in that it can lead people to make art from what is around them, and to take pleasure in true things - like the laughter of children playing in a shallow sea.