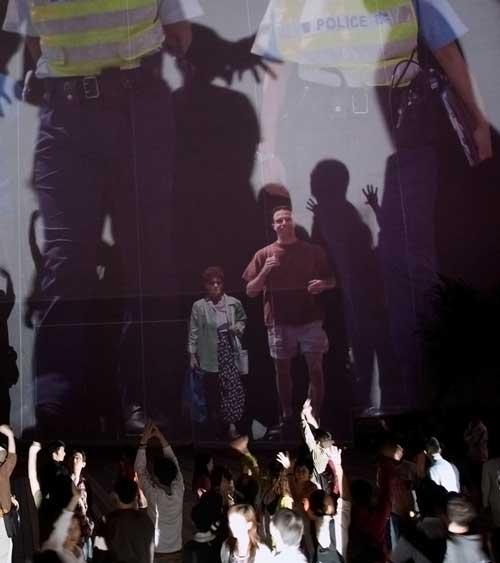

Two shows at the University of Queensland Art Museum Collaborative Witness: Artists’ responses to the plight of the asylum seeker and refugee comprising 17 works, and Waiting for Asylum: Figures from an Archive consisting of the installation ‘protection’, by Ross Gibson and Carl Warner - focus attention on the plight of refugees in contemporary Australia.

Gibson and Warner’s collaboration presents a collection of 69 C-type photographs of asylum seekers on Nauru under the Howard regime’s “Pacific Solution”. Shot by mostly Afghan detainees with disposable cameras provided to them by human-rights activists, these document men, women, and children, engaging in play, relaxation, celebrations, and posing against rocky tropical and marine landscapes. The artists have enlarged the photographs to oversize and added thick stripes of textured blackboard paint across the faces of their subjects.

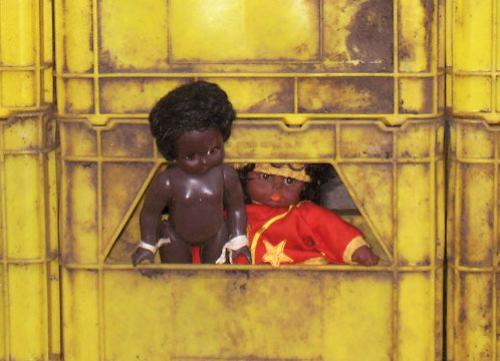

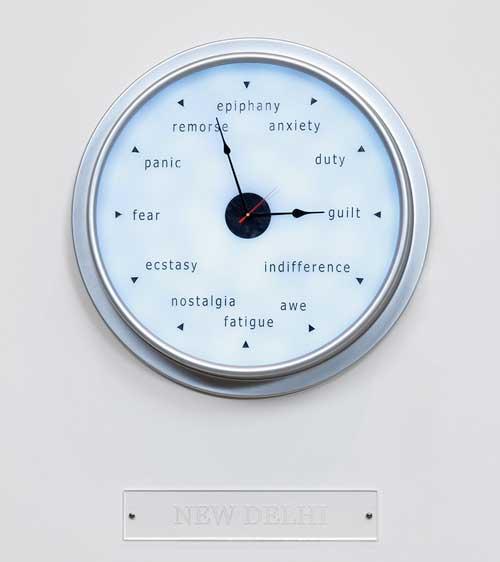

Denying the subjects’ individuality, the black streaks court the danger of continuing, or contributing to, the insistent ‘othering’ of refugees in the prevailing discourse propagated by Australian officialdom and media outlets. These masks, however, are deeply ambivalent; whilst censoring recognition of the human beings beneath them, erasing and turning them into objects, at the same time they are necessarily ‘protecting’ those fleeing persecution from further harm. The series of matte voids across the glossy surface of the photos open up a space into which we can peer into the ambiguity of ‘bare life’ in the ‘zones of indistinction’, of indefinite incarceration in territories, such as Nauru or Christmas Island, which are outside the normal juridical order. The rapid, ragged brushstrokes, slashed across the naked skin of the human face, invoke the various forms of violence to which individuals have been subjected and in which they have been ‘detained’ in routine suspension of human rights within these permanent ‘sites of exception’. And, as Gibson points out in the catalogue, there is another ambiguous metaphor — to remove these masks, and restore identity, will leave permanent scars in the aftermath of the applied protection.

The violence and vulnerability constitutive of refugee subjectivity is also suggested in David Ray’s evocative sculptures in Collaborative Witness. Thoughtfully deconstructing porcelain’s high cultural commodity status, Ray’s wonky tureens and urns gone awry analogise the arrival of today’s “illegals” with scenes of first contact (This looks like a good place to settle, 2010), highlight the historical grotesquerie of forced migration (Tug of war, 2010) and traduce the governmentality that instrumentalises asylum-seekers for political gamesmanship (Safari, 2010). An expressive linearity — sky, razor-wire, desert — structures the brutal planes of Rosemary Laing’s photographic portrait of the Woomera detention centre and you can even pay later (2004) and Judy Watson’s ethereal Surveillance (2009), whose midnight criss-crossing poetically traces an ocean seething with furious ghosts. Jon Cattapan’s Imagine a raft (Mirror boat no. 1) (2003) literalises the white noise that obscures the humanity behind the headlines, while serving to entrench narratives about child-sacrificing ‘queue-jumpers’. As we stare at this painting, trying to see through the splattered screen of extraneous data to the boat behind, a lone figure at the prow of the boat, picked out in grey overpainting, stares back at us.

Several key artists with a long-standing commitment to engaging with the national failure of hospitality, responsibility and ethics towards the persecuted and the traumatised are missing from Collaborative Witness. The musing quote about futility from Jon Cattapan that frames the catalogue essay gives a clue to the tenor of the show.

The uncompromising critique in the work of artists whose work — engaged, and often enraged — has produced new understandings of the real and symbolic violence administered to asylum-seekers in ‘boatpeople crises’ such as Tampa, Children Overboard and SIEV-X, or explicitly located the degrading circumstances of mandatory detention in the system of nation/territory/state that produces refugees, could have made a welcome offset to the show’s essentially polite approach to its subject. Given the mounting scale of the global human tragedy of displaced peoples, and a local context bearing increasing evidence of desperation, and systemic harm, it seems more pressing than ever for people to make and see art that insists on the urgency of resistance to injustice.