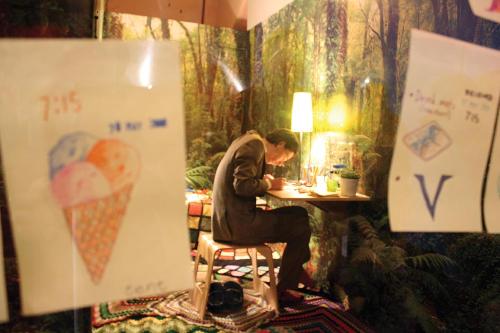

On the cover of this issue is a piece by Agnieszka Golda from a series called Raising the Dead. Golda was born in Poland, came to Australia as an adolescent, studied and lectured in art in Adelaide, returning to Poland to relearn the still-living folk beliefs and culture beyond the cities. Now lecturing at the University of Wollongong, she created an installation at Light Square Gallery drawing on Polish women's shamanism and rituals around raising the dead. There were no labels or lists and nothing was for sale. With its carved pig-like wolves, a stick figure in a fur coat and the embroidered words in animé mode of two tricksters, one dead and one living, bargaining for life or death, the work radiated raw emotional energy. Beyond her calling as an artist/thinker, Golda in this instance was also a curator.

It is thirty years since the rise of the alternative or artist-run space, which emerged out of frustration with the stodginess of art museums and the crassness of the commercial scene, allowing artists to self-curate and group-curate.

Out of this movement of intellectuals, writers and artists has emerged the hydra-like structure of globally networked independent curators who are employed to run the big recurring exhibitions of the world. This matrix is the result of a convergence of research as art, and the maturing of a generation of writers or artists who taught themselves to stage-manage large shows and were given the means to do it.

But now perhaps the writing is on the wall for them too. Was it symptomatic of cracks in the culture of the über-curator that two alpha males chose to play out their bitter rivalry on the neutral ground of Sydney during a curatorial Roundtable convened by the Australia Council? The very public battle of Storr and Okwui Enwezor (curators of Venice Biennale 2007 and Documenta Xl respectively) seemed only to illustrate that each felt his personal beliefs and knowledge had been viciously denigrated by the other. Have the stakes become so high that the old construct of the curator as the all-knowing, all-seeing eye has consumed them?

Contrast this spectacle with the persona of Marcus Westbury who declares in this issue of Artlink exploring the idea of curators as creators, that he doesn't believe in gatekeeping. Not Quite Art, his ABC Television series, follows him into the byways of art production, and via these portals into the age of networked knowledge, of the internet which wraps the world in its embrace, and proves that it can find audiences for any kind of art. The festival that he directed in Melbourne for two editions, Next Wave, has tapped a nerve in our cities.

If the reception of art is a mechanism created by the beliefs and assumptions of the audience[1] there is going to be a problem getting the typical art loving museum visitor to believe that the gallery space is not the only place where art can be seen or heard. But for those who were lured out onto Sydney Harbour to Cockatoo Island for the Biennale of Sydney, the mindset is already breaking down. Felicity Fenner tells us how 'biennale art' can often work very well as an inhabitant of the local place, while Adam Jasper takes the train from Sydney out to the multicultural suburb of Campbelltown to see how a local audience has been enticed into the Art Centre by shows which deal with their place, their issues.

Further afield, the craft and art of curating is following a path in the Asian region which appears to reinforce nascent westernisation. The staff in the growing stock of new palaces of art in Korea and Japan (and much more recently in China), are frequent travellers to Europe and America. Alison Carroll observes that this self-driven dynamism is focused mainly on the biennale end of the spectrum and not on the ongoing business of building and looking after public collections. The tendency to spread the responsibility by forming curatorial teams in Asian biennales is compared with the more individualist West.

Manray Hsu, in discussion with Victoria Lynn frames this idea as an endorsement of the energy-giving practice of collaborating with one or more co-curators on the big shows rather than a failure of nerve. In this he echoes Nada Prjl's discussion of this year's Manifesta where teams of curators commissioned artists who worked with migrants, old people and the mentally ill across the South Tyrol in Italy. Audiences travelled by train between several towns to experience this event.

Curating the idea of international exchange has had a long currency in the artworld, and as global crises overtake us exchange programs assume more urgency.[2] Australia and Japan's long trading relationship translates into the cultural sphere with Hello Tokyo, documented here.

The halo around the profession of the powerful independent curator is hard to shake. The challenge they face in bringing a great Biennale into being after years of preparation to create a mosaic of ideas through visual art, is certainly not for the faint hearted. Artlink writers take a reality check on the glamour stakes with a range of articles about training, career paths (or lack of) and the status of those independent curators who are working at a local, national or regional level putting together exhibitions for which they are personally responsible, creatively and logistically.

Footnotes