Are you an artist, reading this? If so, do you consider what you do as work? The tension between vocation (eg Buddhist monk) and job (eg salesperson) is a constantly swinging pendulum, between living and breathing your occupation and separating your life into work and leisure. At various times and contexts it is possible to do away with the distinction eg for fulltime students or volunteers or perhaps when socially-conscious artists aspired to work with trade unions to integrate art into the working lives of blue collar workers.[1]

This issue samples some of the choices enjoyed by artists today in their working lives and some unusual, even quirky, ways in which this is played out. Guerilla and street art is not a 9-5 job, and residencies are a way of life. There is also a sub-genre of artists who labour at their work, long hours of repetitive actions. A growing acceptance in the society of the notion of collaborative teamwork is perhaps behind the trend for artists to leave the studio for the melting pot of group activity. Concertina, the collaborative group in SA combines forces on a project basis. Others are variously designated as Clusters, Intensive Workshops, and Art Labs in which individuals across arts disciplines are hand-picked for maximum synergy.[2] Here we look at ReSkin organised by ANAT but there are many more. An ongoing Science-Art Lab, Symbiotica, exists at the University of WA. Stelarc has been able to pursue his bio-technology art at the MARCS Lab at the University of Western Sydney with the assistance of a generous ARC grant. The results of the Flinders University Cultural Diversity Cluster were showcased at the inaugural OzAsia Festival at the Adelaide Festival Centre in October in the exhibition Undiscovered Country.

Another escape from solitary work is a new version of the old Australian tradition of bush camps. These might be groups of like-minded artists, or put together by organisations eg @24HR Art in Darwin who in 2007 mixed a group of strangers together, Indigenous and otherwise, for a week or two in a paperbark forest in Arnhem Land. Here Guan Wei reflects on what he got from this experience. Space precludes us including reports on the occasional artist camps run by Bush Heritage Australia on ecologically significant land which it is acquiring, protecting and regenerating all over Australia, the mission being that artists can interpret visually the plight of the land and the need for action to save threatened habitat.[3] Artist Mandy Martin has been a leader in running workshops in their reserves eg Ethabuka in the Simpson Desert in western Queensland and Borradaile in Arnhem Land. In less rugged circumstances, regional cross disciplinary arts residential centres like Bundanon on the Shoalhaven in NSW and Kellerberrin in the wheatbelt of WA combine the stimulus of nature with potential meetings of minds.

Many who over the past 20 years have learned to blend art practice with academic positions in order to gain status for art as research on an equal footing with that of non-art academics, are now struggling to maintain this in the face of techtonic shifts in university core values. The difficulty of finding a natural place for art as research in academia has suddenly become a fight for survival in which those art schools which fail to get over the 'Research Quality Framework' benchmark can lose the right to offer higher degrees. Bang go the art-based MAs and PhDs with which we have all become familiar. There is a way to go before this very convoluted issue is resolved, but most university-based art schools are currently grappling with it.

In another catastrophic shift, the destruction of the CDEP scheme which used to support many artists and artsworkers in Indigenous Centres has caused havoc in the ecology of these workplaces.

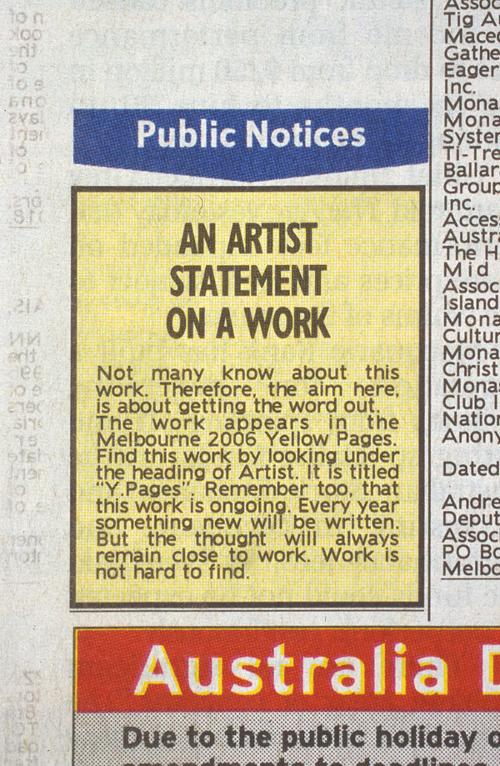

The Howard government's 'Work Choices' package, embodying its current enterprise bargaining-style industrial relations (IR) laws, has created much debate and angst in the population. Beloved of many employers, it is seen by workers to have begun to tip the socially potent work/leisure equation into deficit, setting the agenda for further fraying of the social fabric. In the arts sector, the smartest practitioners have always lived and (and the quieter ones died) by enterprise bargaining – with patrons, dealers, funding bodies, museums, prize-organisers etc – with virtually no reference to the collective bargaining of unions. After all, most artists are sole practitioners who decide what work they do and when. Work Choices. Efforts in the eighties to form an Artworkers Union fell into a tautological hole. How or why would or could artists be affected by industrial relations legislation?

Changes to the nature of art practice have created a new landscape for artists – they work within universities, on residencies, on public art commissions, or in tandem with art museums, and the work of those who become the currency for investor-collectors is sold and resold through the high rolling auction system, run by the likes of Sothebys and Deutscher Menzies. Behind the scenes some big IR shifts have occurred. Michael Keighery's article over the page shows ways in which IR and artists are not altogether strange bedfellows.

Finally, for the philosopher's view on work, we asked Donald Brook to respond. His The Work of Art takes us back to the big picture.

Footnotes

- ^ Poetry readings by living poets to members of the builders labourers union on building sites were apparently not only tolerated but enjoyed. But this faded away. See Before Utopia – A non official Prehistory of the Present Ian Millis interviewed by Helen Grace. http://www.ianmilliss.com/documents/BeforeUtopiaInterview.htm

- ^ These have been pioneered by the Australian Network for Art & Technology and the Multicultural Committee of the Australia Council in tandem with organisations like Flinders University Drama Dept, and The Performance Space.

- ^ See www.bushheritage.org.au/