Turbulence, this year's 'Third Auckland Triennial' doesn't have the diffuse enormousness of the 2006 'Biennale of Sydney', or the acquisitive institutional focus of the current 'Asia-Pacific Triennial', but it still seems, somehow, a little too much to grasp. Too many talks and performances to attend, hours of videos and movies to watch. Spread across the Auckland Art Gallery, Artspace, the Gus Fisher and St Paul Street Galleries, as well as the Academy Cinema, the event becomes a game of stringing together the artworks, a task of joining the dots between venues and serendipitous encounters with engaging work. Curator Victoria Lynn's thematic of 'Turbulence' ('we live in turbulent times', runs the catch-phrase) is name-checked almost every few paragraphs in the catalogue. Previously a Director at Melbourne's Australian Centre for the Moving Image, Lynn's apprehension of turbulence seems fixed on the political and economic. The question is, of course, which times were not turbulent, and to what extent are our times more mixed-up than, say, 1939, or 1968, or 1972.

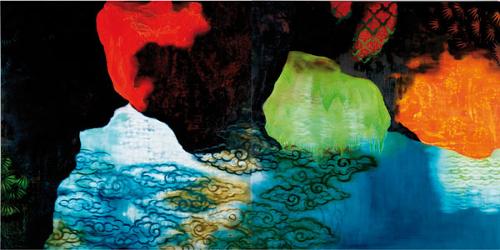

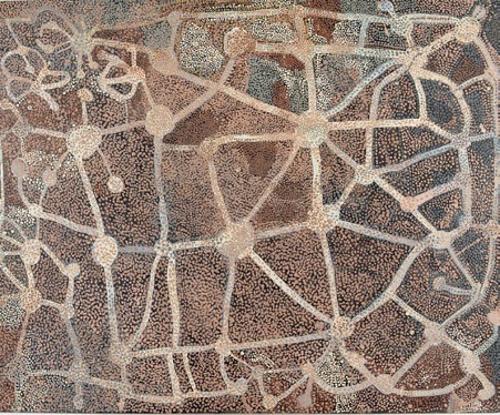

One room that staked out her ideas more eloquently than any statement of intent contains 'Kehe Tau Hauga Foou (To All New Arrivals)', huge white canvases by New Zealand/ Niuean painter John Pule. Connecting the patterning of 'hiapo' (traditional Niuean bark cloth) with a wavering and eloquent line, groups of small scratchy figures struggle upwards, eclipsed by smears and dripping blots, pattern, clouds and climbing vines. A New Zealand artist now based in Hong Kong, Yuk King Tan's wall drawing, 'Boomtown' is based on a Chinese propaganda painting. Conglomerations of oil-rigs and refineries are strung together from firecrackers. The red and green wrappers of the partially exploded crackers litter the floor, while a shiny red fire extinguisher nearby speaks of their remaining incendiary potential. Tan's smoky oil-rigs face the videos of Israeli/US artist Michal Rovner. Rovner's three works are displayed on those little LCD screens made to emulate photo frames. The seemingly photographic frames make it possible to be caught by surprise by the images' subtle movement. Based on footage the artist shot in the oil fields of Kazakhstan, the screens show oil pumps moving dreamily, dark rivers flowing underground, black smoke streaming up into the sky.

Isaac Julien's self-consciously sublime three-screen Arctic video 'True North' was seamlessly installed at St Paul Street. Referencing the journey of Matthew Henson, the African-American who first reached the geographic North Pole, the work had the beautiful exoticism and icy sheen of a vodka advertisment.

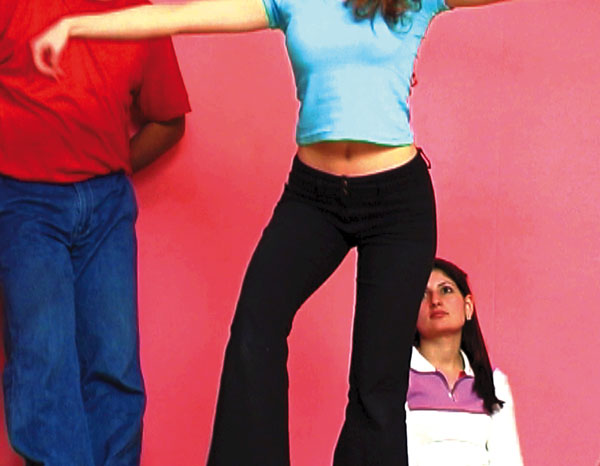

Phil Collins recruited Palestinian teenagers from the Israeli-occupied town of Ramallah for an eight-hour dance marathon. 'They Shoot Horses' connects the often brutal depression-era dance marathons with the gauntlet of life in the Occupied Territories. Punctuated by calls to prayer and powercuts, the two-channel work is projected loud, in a dark, disco-like room. The young dancers are shy and slightly awkward, their enthusiasm waxing and waning to the music, as they dance to the point of exhaustion.

In contrast to Julien's glistening production values, or Collins' thumping soundtrack and saturated pop-video colouring, the videos of Regina Jose Galindo evoke the kind of political violence only alluded to in other works in the show. In 'Limpieza Social (Social Cleansing)', the naked artist is sprayed with freezing water from a high-pressure anti-riot hose. In 'Quien Puede Borrar las Huellas? (Who Can Erase the Traces?)' the artist dips her bare feet in a basin of human blood, trailing gory and accusing footsteps from Guatemala's Palacio Nacional to the Corte Constitucional.

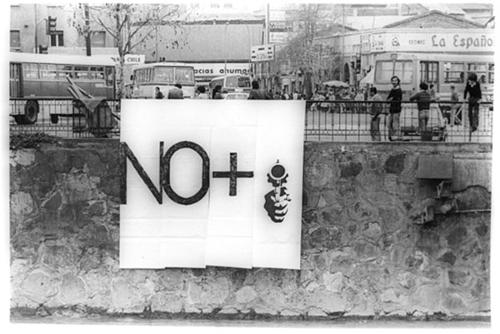

More allusive, but as affecting, Colombian artist Oscar Munoz' work 'Aliento (Breath)' possesses a very simple interactivity – no sensors or touch-pads, just the warm breath of the viewer on a series of metal discs. The condensation reveals ghostly photographs of the disappeared, images that remain visible for a moment, before the breath evaporates, leaving smooth, shiny metal.

Although unsympathetically installed in a narrow and busy corridor at the Auckland Art Gallery, Uzbekistani artists Vyacheslav Akhunov and Sergey Tichina's video 'Ascent' recalls the reflexive video gestures of Bruce Nauman, but within an utterly different time and context. 'Ascent' shows Tichina effortfully climbing the rough, steep, seemingly endless spiral steps of a tower in the historical centre of Buchara. The shot is hemmed in by stone walls. After finally reaching the top and surveying the domes and roofs of the surrounding city, Tichina brings out a laptop, opening it to view the footage of his climb. The view collapses back into the screen, as the journey loops back to its start point.

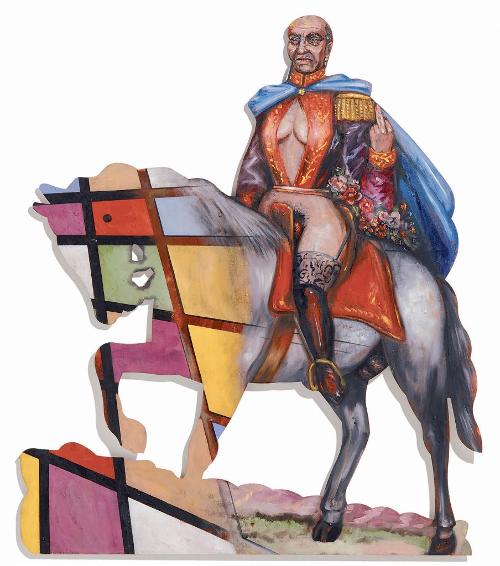

The Triennial has a democratic spread between old and new media, from figurative painting, to installation and video. The show is light, however on sculptural objects. Much work seems easily packed down and many of the pieces in the show have had lengthy itineraries: Venice, Shanghai, Istanbul, São Paulo& Addressing this flow and portablility, two works on the theme of currency have a particular delicacy and weightlessness. Australian Fiona Hall's 'When My Boat Comes In', a large series of monochromatic botanical paintings on outmoded paper money, is a meditation on liquidity, origins and expropriation. Gouaches of economically important and heavily traded plants overlay the engraved submarines, Viking longboats and clipper ships of the folded and worn notes. Cuban artist Carlos Gariacola's 'Postcapital' is a tabletop model city populated by figures from coins and bills. Bounded by a tiny treed and street-lit highway, Gariacola's intricate models of treasuries and parliament buildings share space with antelopes, giant penguins and the busts of mysterious potentates.

The show's only truly weighty work is the brick moon gate installed in the window space of St Paul Street. The gate forms part of The Long March Project's 'No Chinatown', a collaboration with Auckland artists Daniel Malone and Kah Bee Chow. Auckland lacks a designated Chinatown in the style of Sydney or San Francisco. The artists ask: should Auckland have a Chinatown? Does it already have one? What constitutes a Chinatown? The project started weeks previously at the Lantern Festival, with questionnaires polling visitors to that city-run celebration of Chinese New Year.

A point of intersection and an interrogation of the notion of place and belonging, the work is dispersed across three venues, and operates differently in each. Artspace showed placards and piles of questionnaires, along with the video 'Ciao From Sum Auld Guy', faux investigative journalism morphing into a cheesy Chinese vampire movie, with a climactic supernatural showdown between Malone and Chow. The planned accompanying 'Short March' (a hikoi along Auckland's waterfront) was cancelled because of a failure to secure permission from Ngati Whatua, owners and traditional inhabitants of Bastion Point, the march's planned endpoint.

An architectural competition housed at the Gus Fisher Gallery asked visitors to construct models from bags of cardboard scraps and chopsticks, while a low-power radio station broadcasting from the building created an ethereal Chinatown of the airwaves. Amongst all these scattered activities, the moon gate, standing solidly behind gallery glass, stated in one hit what all the other pieces were reaching toward.

Although 'Turbulence' speaks of churn and dislocation, the nation-state still frames the conversation – artists are clearly labelled with their countries of origin and residence, although much of the artwork contests these boundaries. With its disparate methodologies, its failures and successes, its varied appeals to the art aficionado and the passer-by, 'The Long March Project' seems like a microcosm of the pleasures and vexations of the triennial itself.