Oh, how we long for the metaphysical! But, oh, how foolish this longing is. Anne Wallace's highly cinematic paintings, and, indeed, the protagonists within them, lead us to the brink of metaphysics. Wisely, however, they almost never take the final leap.

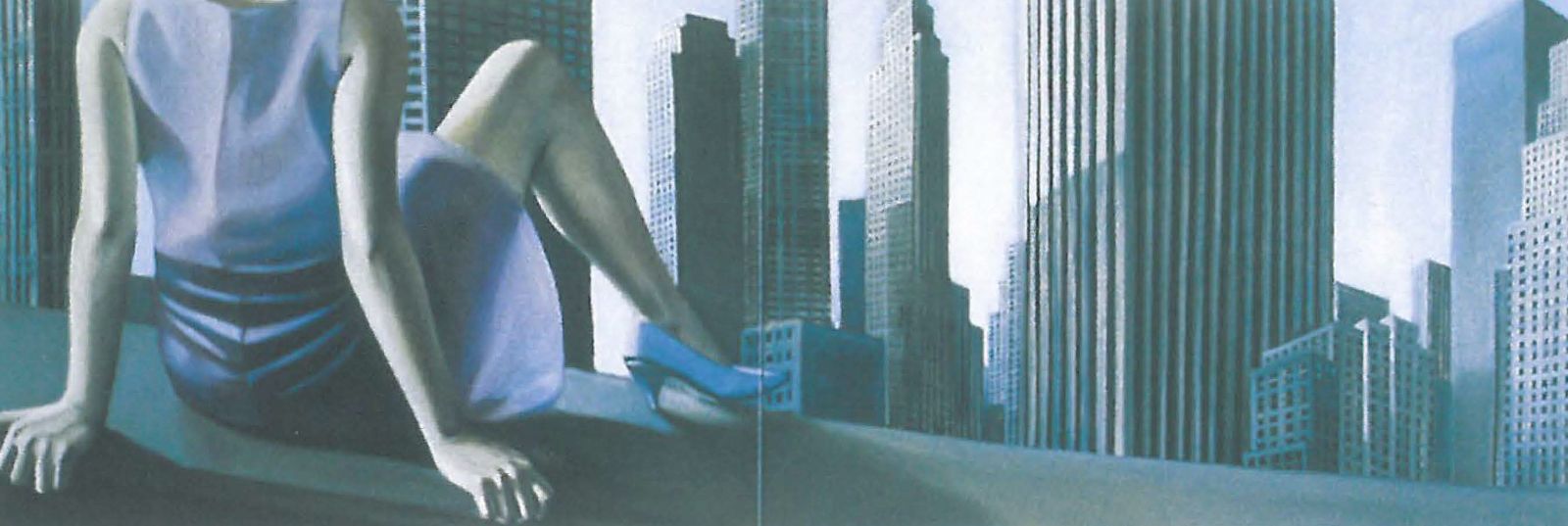

In Wallace's Springtime, for example, a girl in high heels and party dress sits with her back to us on a precarious ledge overlooking highrise buildings. The melancholy de Chirico stillness of the woman's surroundings begs for a disturbing breeze. While her stockinged knees spread wide to invite the rising city, or perhaps its immanent spirit, the knuckles of one hand desperately knot to hold the ledge. This combined metaphor of apprehension, wistful openness, and corruptive potential teeters between the monumental and the sublime.

But do these images peek into a dark cauldron of the artist's unconscious, or do they signify something externally real, solid, 'verifiable'? Neither. No more individually psychoanalysable than were the works of Dali in Freud's own estimation, they operate in a linguistic register. The languages Wallace plays with are those of Hollywood film and of the surrealist/metaphysical schools of painting. Their style suggests a genealogy that could include David, Ingres, De Chirico, Magritte, Edward Hopper, Eric Fischl, our own Geoffrey Smart and Peter Booth, and, philosophically, even the late Renoir and the late Cezanne.

Wallace's brushwork is synoptic: images are rendered just generally enough to recall eternal Platonic forms, but sufficiently detailed to seem real and specific. Thus the young girl in her pictures is at once particular and generic. And each image is like a single frame removed from a filmic narrative.

Sometimes, too close an adherence to her genealogy lets Wallace down. The picture titled Still Air, for instance, has a candelabra extinguished in all but one of an infinite play of its reflections in a mantelpiece mirror. That single lit candle has no possible cause in reality and hence attempts to depict the noumenal in presentia. This is a perilous tactic because the noumenal, metaphysical, world from that moment becomes mundanely phenomenal. The metaphysical, once attained, spells the death of change and uncertainty - which, after all, is what life is. Moreover, a cinematic frame enlargement with no before or after: what are its implications? Does it posit an action with neither history nor consequence and therefore no politics?

Wallace's most successful images, while they do not explicitly embrace politics, can neither be said to evade them. They force you to mis-categorise; they disrupt the normal squares of opposition. They seem postmodern politically rather than aesthetically, for example, and perhaps more feminist aesthetically than politically. They work best when they subvert her influences.

One painting, Sight Unseen, depicts only a door with a puddle of water seeping out under it. Reflecting the institutional green of the room, the pool of water is a bilious verdigris. However, what is threatening is not this image itself, but what may have caused it: something intangible, noumenal, whose true nature always escapes us.

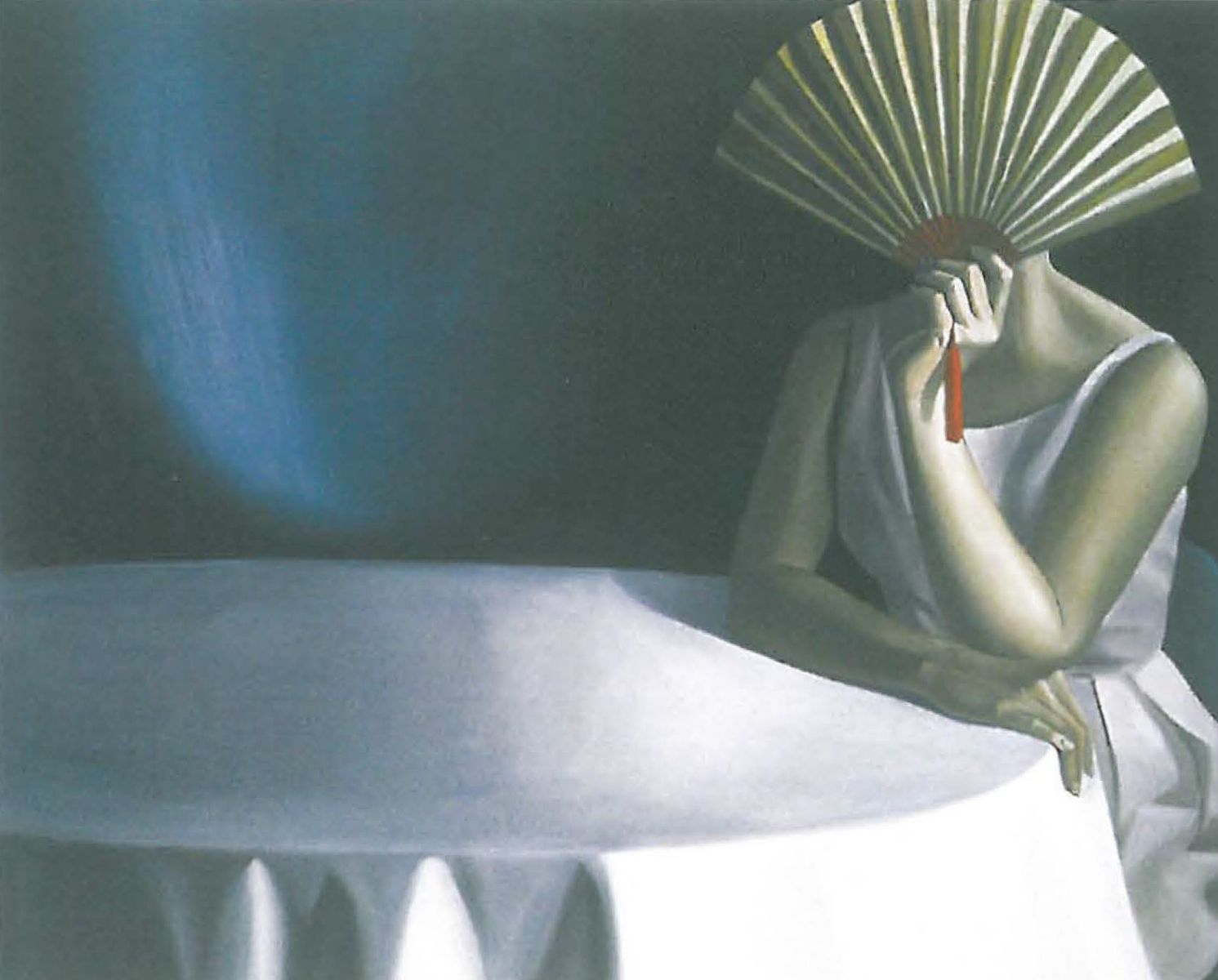

While the language of these images purports to be both metonymic and indexical, we are forever denied not merely their referent, but also their signified. According to Lacan, what lures our eye into a 'blind spot' oblivious of its subjectivity is the 'gaze' produced through perspective. In contrast to this is what Norman Bryson terms the 'glance' which is anchored in history and desire. Wallace uses this difference to subvert the Lacanian perspectival trap and weave a trap of her own. A Glance Away, for example, depicts a woman far more individuated than most of Wallace's other protagonists looking to something outside the picture space. In cinematic convention this is an invitation for a reverse shot - a close up of what she is looking at. But in this picture this is precisely and absolutely what we are denied.

Similarly, Perfume depicts a business-shirted young man against a cityscape vista savouring an invisible aromatic presence denied us in every way except through imagined identification with his experience.

We are led to identify with each picture's point of view but not to attain it. This is not then simply a matter of placing ourselves at the omniscient monocular position of the perspectival eye. We have to place ourselves into a picture from which there is no escape.

It is not that there is no history or consequence, Wallace's best works tell us, but that we cannot ever truly know these - despite being obliged to accept responsibility for them.