There have been reports in the media of late covering the celebrations over Michelangelo's David hitting 500 years old. The work is one of a handful of the planet's most recognisable artworks; it quite literally embodies that era when the spirit of humanism, and the sensuality of the human form, wrested the conception of Homo Sapiens from the grip of religion – even if the subject is straight out of the Old Testament. Half a millennium on, where has all this dedication to figuration got us? Well, the show Life is very long at Yarra Sculpture Space might give us a few clues. The catalogue pointed to the challenge of figurative representation as a pursuit, but the thing that seemed to link the work of the artists in this show is the weight of history, of all that making that has gone before. To tackle the task in the spirit of the heroic as of yore is a recipe for kitsch (and I'm talking bad kitsch here). The artists in Life, however, canny graduates of the School of Latter Day Duchamp, are guided by the old wag's irony.

Nick Devlin's peephole dioramas would have done Marcel proud. The viewer, nose pressed to the wall, was treated to tiny scenes of artists at work. These vignettes presuppose an art-literate audience: to enjoy the wit, it helps to know the subjects. Chris Burden, for instance, shows the multi-media artist depicted in the act of having himself shot as an artwork. Jackson Pollock is a reproduction of a scene from a documentary film of the artist, standing on a sheet of glass before the camera and letting fly with the paint. One way or another all of Devlin's pieces refer, implicitly or explicitly, to the role of photography, cinema and video in the way we come to know about art, and its role in art practice and myth-making. In case the viewer missed the point, the end piece on the wall, Automatic self-portrait, consisting of a small flat screen connected to a micro camera, provided the viewer with an image of himself staring at himself.

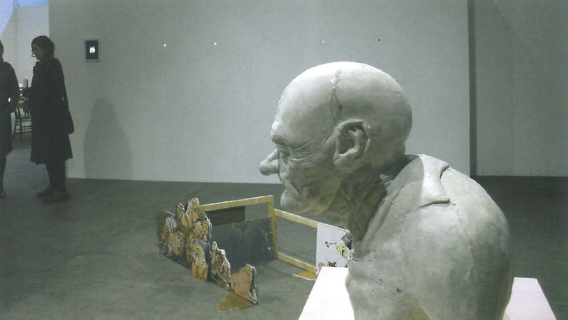

Michael Bullock's Little Big Man (a self portrait at 121 years old) offered another view of the self, a bust of the artist transformed into an ancient. The title of the piece is taken from a film of the same name, and Bullock's working method is based on the techniques of the famed make-up artist Dick Smith. The piece also brings to mind the work of Ron Muecke, another sculptor who has refined his skills through work for films and television. Bullock does not appear to be chasing the sort of verisimilitude that Muecke is seeking; rather, a caricature that falls somewhere between being a kind of memento mori and an extra for a George Lucas extravaganza.

Steven Rendall's contribution had the effect of a jumble in the studio, a chaos built from this obsession with self and self-representation. A studied agglomeration of heads of the artist, the work appeared to be on the wrong scale. The light structure supporting the portraits had the look of a rudimentary stage set, or rather a maquette of one. With its faces executed in a loosely posterised, somewhat expressionist technique, with overtones of disintegration, the piece lacks the elegance of other recent works by Rendall, deconstructions of work by old masters. This appears to be deliberate: an attempt to convey, in concrete form, a degree of vertigo and dismay that can lie at the heart of self-investigation.

In marked contrast to Rendall's piece, the small, solitary painting of Jon Jones appeared quite straightforward, almost out of place. The catalogue informs the viewer that the artist's subjects are celebrities of one sort or another. Based on a black and white snapshot, the oil shows a man and child walking along a street. Clothes and cars suggest the original snapshot was taken around the 1930s or 40s. Text on the margins of the oil constitutes a private code of the artist. By this device the piece may be 'read' as one element of an art practice which acts as a form of diary, no doubt therapeutic if somewhat obscure.

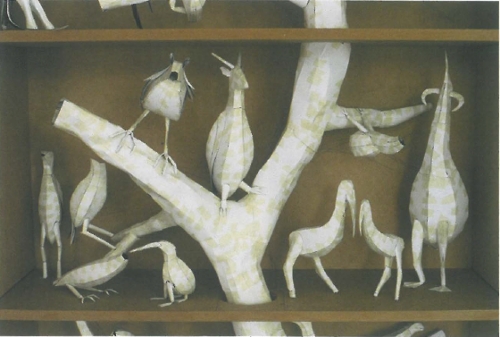

The three heads of Justine Khamara also employed photography, but directly, as a plastic medium. Each head is made of a sizable number of photographic prints, each print being a detail of the subject's head. Fixed together, the photos balloon out the form of the skull, the features of the individuals weirdly stretched across this glossy membrane, which by turns has a flaky or scaled appearance. There is something decidedly macabre about these objects: a feeling that they might be right at home with the trophies of a killer with a penchant for flaying his victims. Khamara's hollowing-out of her subjects may be an apt metaphor for this time of Hannibal Lecter: perhaps reality is no more than skin deep.